By Claire Blaha

Editor’s note: Part one in a multi-part Advocate series on the opioid epidemic on Long Island.

Growing up on Long Island, Julianna Domiano, 21, knew little about opioids besides the minimal information that she was provided during school assemblies. That was until, one by one, the opioid epidemic swallowed up her classmates and friends.

Domiano’s neighbor and best friend growing up went to rehab for two months in high school, overdosed and then died in his childhood home. “Two months later another kid died. Three months later another kid died,” she said. “I ended up dating somebody who was addicted to heroin. It was everywhere.”

These experiences deeply affected Domiano and determined her future career path. “I watched one of my best friend’s boyfriend[s] overdose in front of me, and I had no idea what to do at the time. I was 17, I was in a hotel in New Jersey,” she said. “So, feeling kind of powerless in that situation really persuaded me to go into the medical field, which I never would’ve thought of before.”

Now Domiano works as a full-time emergency medical technician and has an internship at an obstetrics and gynecology office as a phlebotomist, drawing blood from patients. She is working to get into nursing school.

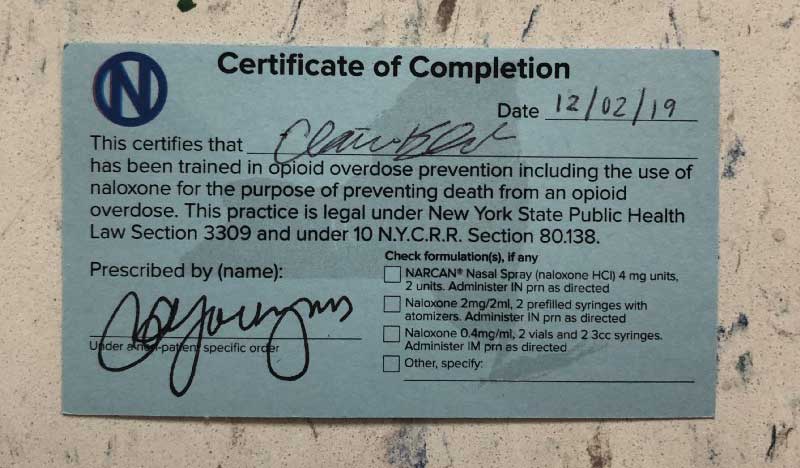

In 2006, New York state passed a public health law that allowed non-medical personnel to be trained to administer Narcan. With opioid overdoses on the rise, many believed that spreading awareness and giving more people the ability to stop overdose deaths would be a step toward ending the looming epidemic.

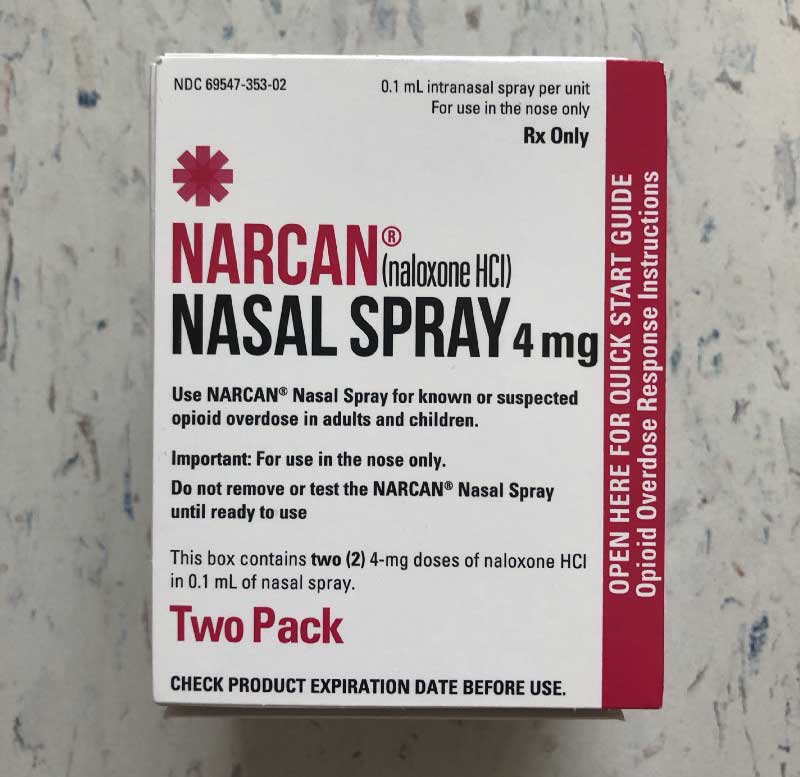

Narcan is a prescription drug that you can buy at a pharmacy or get after attending a training. This author received this as well as an instruction kit with gloves when I attended a training conducted by David Hymowitz at the East Meadow Fire Department.

Naloxone, more commonly known by its brandname Narcan, is an opioid antagonist. Its chemical structure is similar to an opiate. It pushes dangerous opioids off receptors sites in the brain and takes their place, but it is not psychoactive, meaning it does not produce a high or even reduce pain.

When Domiano was in trade school to become an EMT, she learned all about the pharmacology behind Narcan, but she was not trained to use it until orientation for her job. EMTs and paramedics had had access to Narcan long before it was sold in pharmacies and given during trainings, but its availability has increased to potentially decrease the number of overdose deaths that happen every year.

For the past seven years, the Nassau County Office of Mental Health, Chemical Dependency and Developmental Disabilities has provided community-based Narcan trainings for whomever wishes to attend. David Hymowitz, the office’s director of program development, runs a seminar titled “Behavioral Health Awareness” and has trained over 15,000 people in the county.

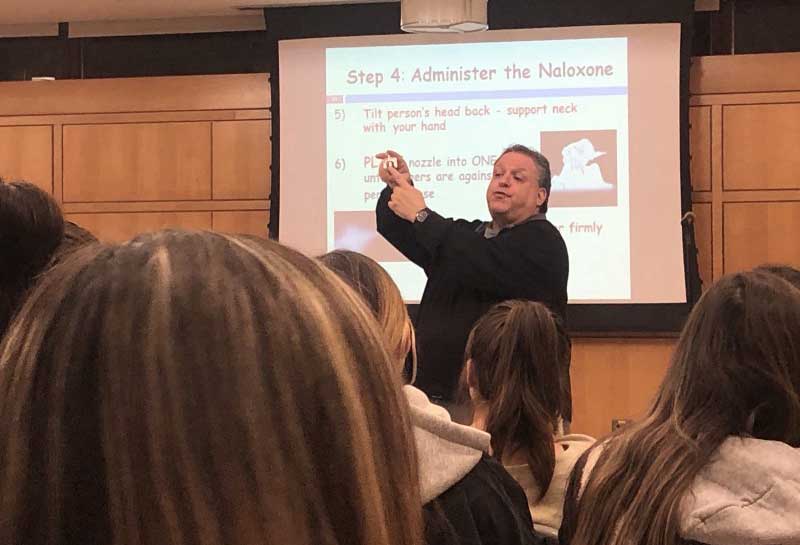

I attended two Narcan trainings that David Hymowitz held, first at the East Meadow Fire Department and then in the Sondra and David S. Mack Student Center at Hofstra University.

“It’s all about the different types of training and education, anything related to mental health, substance abuse and the interaction between the two,” he said. He has conducted more than 400 Narcan trainings in seven years, with at least three or four every month.

Along with a presentation about how Narcan works and how to use it, these trainings include lessons on the different types of opioids and how to recognize the signs of an overdose.

When Domiano arrives at the scene of a possible overdose, she looks for constricted pupils, respiratory depression — when a person is breathing at a rate of eight times a minute as opposed to 10 to 12 times — and unresponsiveness.

This card is my certification to use Narcan. You receive this with your Narcan kit at the end of the training.

In his trainings, Hymowitz covers the same information. He also discusses how to properly handle people once they have been revived with Narcan, important for anyone who finds themselves in this stressful situation. “It takes the receptor sites, it cleans them out, and that causes someone to go into withdrawal,” he said. Immediate withdrawal can be dangerous, and it’s important to assess the scene accurately to ensure the safety of everyone involved.

Access to resources and personal stories are also shared at the trainings that Hymowitz conducts. On Nov. 12, at the East Meadow Fire Department, Hymowitz held a two-hour training that started with speakers representing the fire department, Narcotics Anonymous and Confide Counseling Center, and ended with the instructional presentation.

David Hymowitz, hosting a Narcan training at East Meadow Fire Department on Nov. 12.

Nicole Philippou, a Confide recovery coach, spoke about the work that she does and her past personal struggles with opioid addiction. At the age of 11, she was molested, and started smoking marijuana and drinking alcohol to cope with this painful experience. She eventually graduated to crack and heroin.

“It ended with me being 92 pounds, soaking wet and wanting to put a bullet through my head,” she said. “My life was just falling apart, so I made the decision to get clean.” Philippou went through a 28-day rehab program and started going to Narcotics Anonymous meetings.

After getting clean, she worked to become a CASAC (credentialed alcoholism and substance abuse counselor) and opened two women’s sober houses. As a recovery coach, she now helps former addicts outside of the counseling center by accompanying them to their mandated court dates or by exercising with them to cope with their recovery process.

Philippou never had Narcan used on her, but there are people out there who have similar stories and were saved from dying from an overdose with Narcan. With the idea that a drug can bring a person back to life, it can be thought that opioid addicts will only take advantage of Narcan and continue to use opiates.

“There are some people that are just not ready to stop, but they don’t want to die,” Hymowitz said. “ So, on some level, there are people who definitely see Narcan as, ‘Oh, this is a way that I can keep on getting high.’” His hope is that addicts will use this second chance to turn their lives around.

Elaine Squeri, the director of health services for the Woodmere-based Tempo Group, a non-profit counseling center, focuses mainly on patients’ medical care, including their physical and mental health. “Narcan is effective in that it keeps people alive and hopefully gets them into treatment,” Squeri said. With a second chance at life, former addicts need treatment and support in the process of becoming clean.

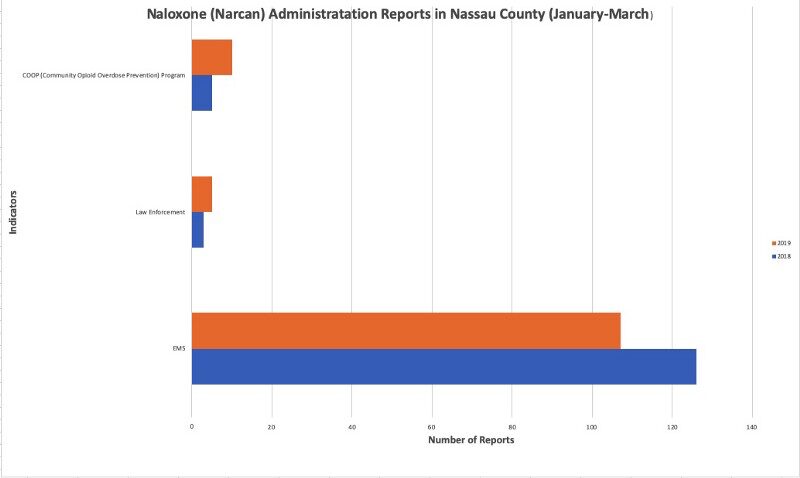

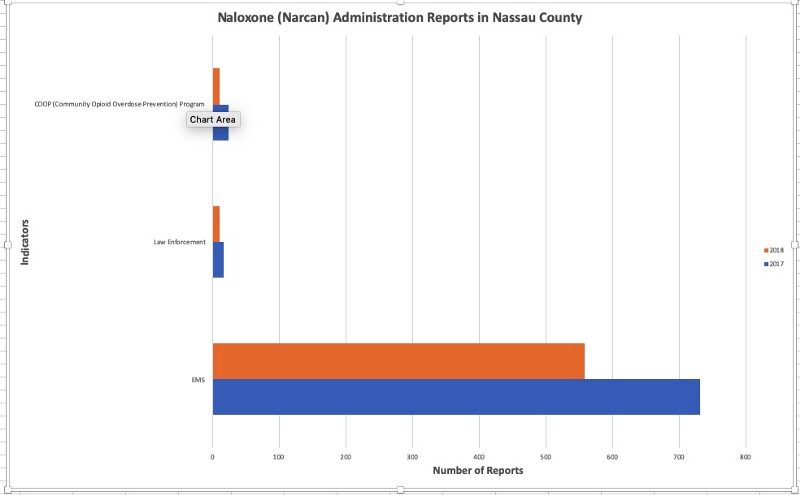

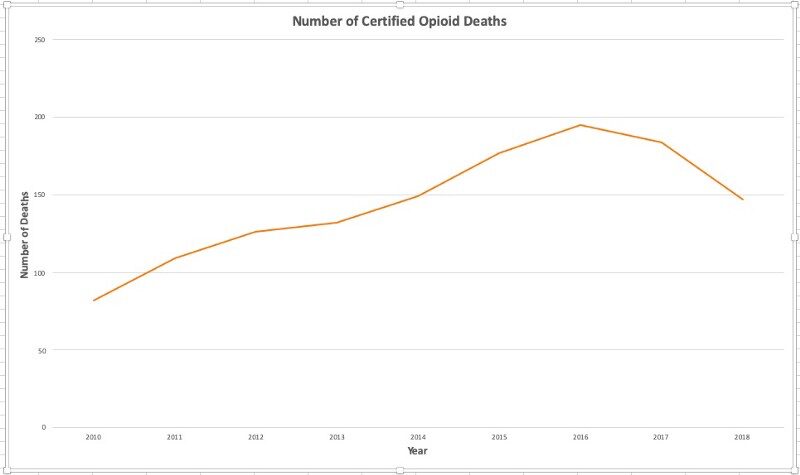

And statistics from the Nassau County Medical Examiner’s Office show that, over the past few years, fewer people are dying from opioid overdoses. “There is definitely a decrease in opiate deaths on Long Island due to Narcan public awareness,” Squeri said. It is difficult to claim that it is the sole reason for this decrease, but educating and spreading awareness is an important step in the fight against the opioid epidemic.

“It’s never one thing that’s going to make a difference when it comes to an epidemic of any kind of a drug,” Hymowitz said. “So it takes everything. It’s the law enforcement piece of it, it’s the public education.” He does not believe that Narcan is the solution to the opioid problem, but as long as people continue to attend trainings, he believes that there is still hope for the future, he said.

Despite never being “Narcanned” herself, Philippou knows the power that the experience can have. “I have plenty of friends who overdosed, and it was used on them. And that was their jarring experience that made them realize that they needed to get their lives together,” she said. It cannot be ensured that addicts will receive this wake-up call positively, but it’s still a wake-up call.

“I think it’s very important that people learn how to do this, especially in New York state. It’s a very terrible thing here,” Domiano said.

Seeing how this epidemic has affected the area, both from a personal and medical standpoint, she understands the importance of education and awareness. “You would never know that your friend is addicted to an opiate or something, but God forbid you see it happen, you know the signs because of your training and you do it,” she said. The more people who are trained to use Narcan, the closer Nassau County and the rest of the country can come to ending this devastating epidemic, she believes.