By Anna DeGoede

Part one in a series featuring stories that appeared in the 2022 edition of Pulse, the Lawrence Herbert School of Communication’s annual student-created magazine, titled this year as Pass the Plate. Pick up your copy at the Herbert School.

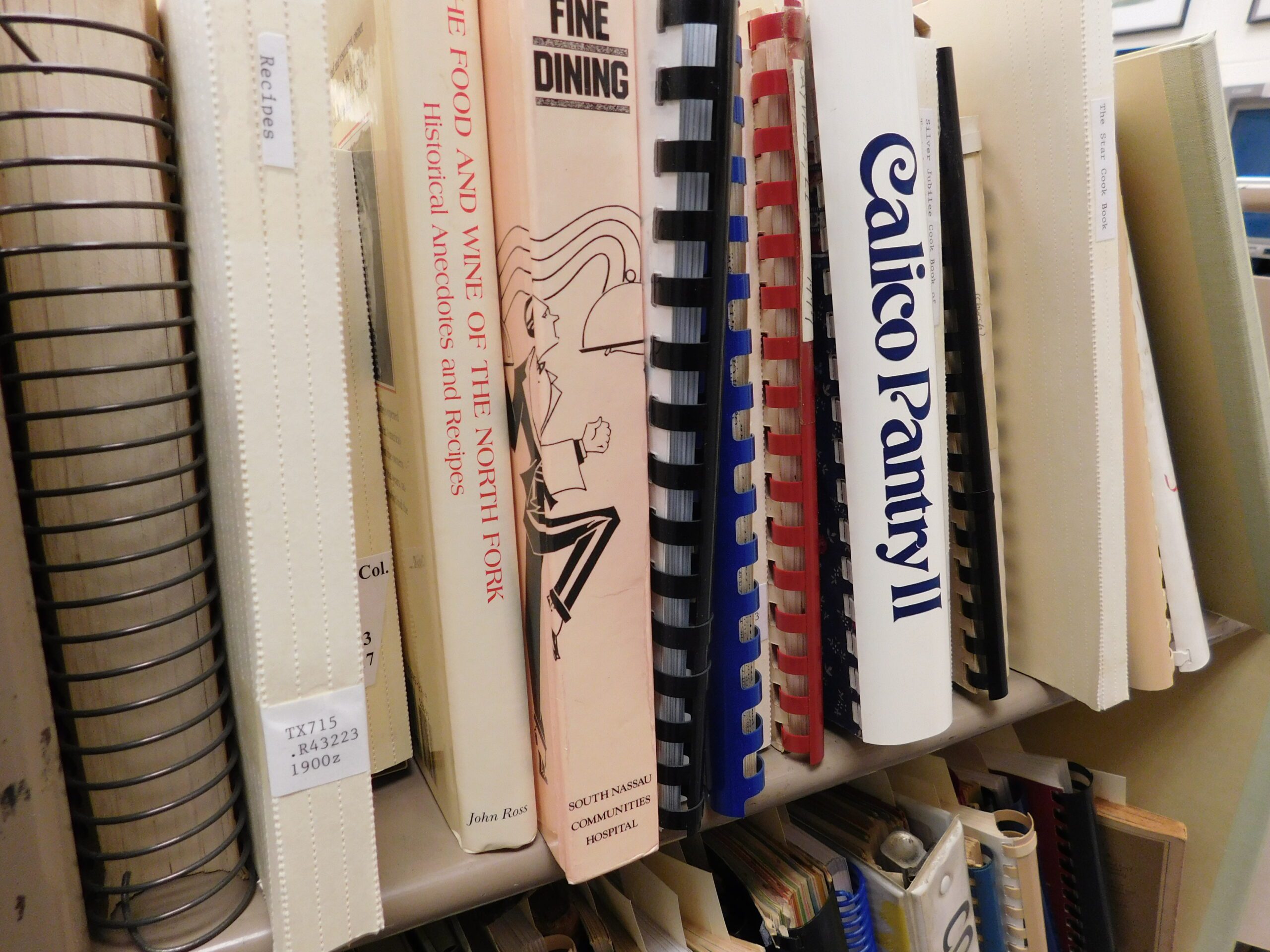

A rickety library cart full of aging books with handwritten titles, rarely touched, holds an unexplored wealth of vibrant, tantalizing cooking recipes and meals. The cookbooks found on this cart in Hofstra University’s Special Collections are yellowed with time; their brittle pages and spines feel as though they might flake off into pieces at any moment.

In the reading room, which is accessed through the bottom floor of the Axinn Library, the cookbook authors are church and community members from different Long Island towns. Recipe origins extend from Hempstead to Islip and Bridgehampton, with themes ranging from Mediterranean to German and Jewish recipes.

A majority of the cookbooks were brought into the collection by acquisitions curator Bronwyn Hannon, according to Michael O’Connor, a consultant with the Special Collections Department. Although Hannon’s job was a casualty of the Covid-19 pandemic, the collection that she curated remains a striking legacy of her work, featuring a wide variety of cookbooks from across Long Island starting as early as the 19th century.

“The cookbooks from the 1800s were already at Hofstra, for whatever reason, because they are an essential part of Long Island history rather than for a cookbook collection specifically,” said Debra Willet, senior library assistant for the Long Island Studies Institute.

Reading chronologically through the titles is like taking a time machine and jumping through fragments of the past. Recipes titled along the lines of “World War I Cake” in one book and “Blitz Torte” in another serve as a reminder of the history contained in the unassuming spiralbound books.

Although the large-scale consequences of wars provide the most obvious historical lens through which to read these cookbooks, a more subtle factor that influenced these recipes was the advancements in food science when each cookbook was published.

Professor Sharryn Kasmir, chair of anthropology and director of the food studies minor at Hofstra, suggested that cookbooks often showcase common household cooking items that were common for the members of the organizations that compile the recipes for each book.

They’re kind of self-produced, self-published books, and those recipes contain items that would have been popular or common in households at the time. Canned vegetables or Jell-O molds in the 1960s would be a really historical telltale.

Professor Sharryn Kasmir, Anthropology Chair

“They’re kind of self-produced, self-published books, and those recipes contain items that would have been popular or common in households at the time,” Kasmir said. “Canned vegetables or Jell-O molds in the 1960s would be a really historical telltale.”

In fact, Jell-O, which is known as gelatin in its unbranded form, rose to prominence in the 1900s and into the Special Collections cookbooks simultaneously. One book, Bridgehampton’s 300th anniversary cookbook, which was published in 1956, contained numerous recipes using gelatin.

One of the several gelatin recipes in that cookbook was lime sherbet, provided by Mrs. John Naylor. The ingredients list for this dessert is relatively normal from a modern perspective: water, sugar, lime zest, lime juice, egg whites and, of course, gelatin. The result: a fresh, icy, citrusy dessert for a hot summer’s day.

However, as the novelty of ingredients like gelatin wore off, so did the number of times trendy recipes such as lime sherbet appeared in the cookbooks. By the end of the Special Collections shelf, there are little to no gelatin salads present.

Gelatin was not the only ingredient to undergo a shift in popularity. Shellfish grew in prominence over time, too, according to Charity Robey, a food journalist and member of the Culinary Historians of New York. Unlike gelatin, shellfish continued to become more highly sought after as time progressed and never faded from favor.

“If you look at books from the ’50s on Long Island, you may find recipes for shellfish and for different kinds of fish, but they’re not going to be recipes, for the most part, that are for company or that are fancy, because at that time that was not really considered to be fancy food,” Robey said.

Even shellfish recipes from a copy as late as the 1974 “Oysterponds Country Cookbook” remain relatively understated: Community member Carole Luce’s scalloped oyster recipe contains no hints that this dish might be served at a dinner party, and the ingredient list requests only oysters, milk crackers, butter, milk, pepper and paprika.

Other recipes from the Special Collections cookbooks feature more unconventional ingredients because of the various cultural influences different communities on Long Island have had on their creation.

“If you look at cookbooks across different communities, it tells you a lot about cultural distinctiveness, but also class differences, race differences and work,” Kasmir said.

For example, in “Iranian Kosher Recipes,” written by Ester Moreh, a member of the Ester Chapter of Hadassah in Great Neck, a recipe for koresh nana jafari features kiwi, mint and apple — ingredients that non-Iranians might have never cooked with in tandem.

Similarly, “Midway’s Favorite Kosher Recipes,” compiled by the women of the Midway Jewish Center in Syosset, highlights a wide variety of Jewish recipes. Matzah balls, challah and Israeli salad are just a few of the recipes found in this book. Here, preparations involve locating ingredients difficult to find in grocery stores where there is not a large Jewish population, such as pareve margarine, lekvar and matzah meal.

Willet said that while the collection is extensive, Special Collections will continue to keep an eye out for more diverse food cookbooks. “The only way we could acquire more is if it were produced by an ethno-geographic location, for example a Hispanic or Asian community. If any of those communities put out a cookbook, we would be interested in that,” she said.

Ultimately, cookbooks will continue to be impacted by current events, developments in cultural diversity and technological advancements. Although there may not be as many print cookbook options to add, as the rise of the Internet has led to an abundance of online recipes, the lasting legacy of the Special Collections community cookbooks reminds us of the meals, drinks and desserts that came in the decades before today.