Advocates: Workplace exploitation is a national concern

By Scott Brinton

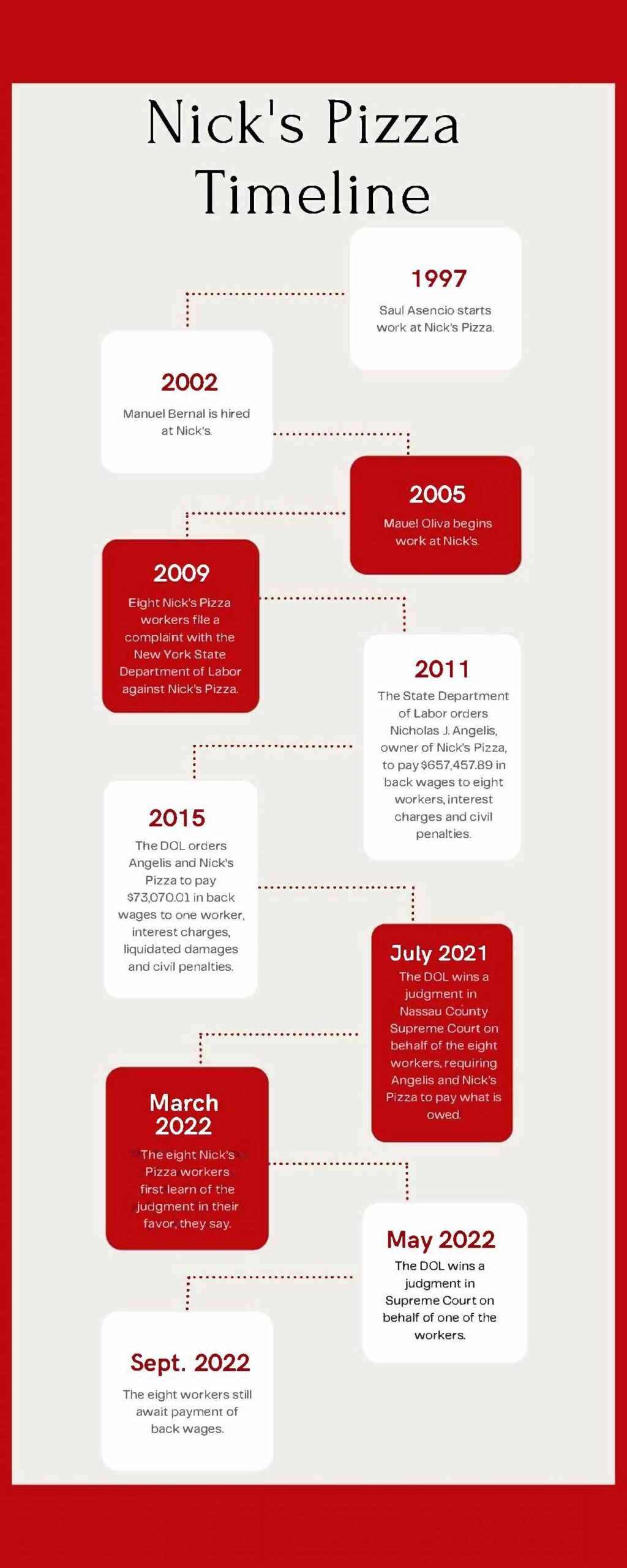

Despite a July 2021 Nassau County Supreme Court judgment in their favor, eight kitchen workers are yet to be paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in back wages that they are owed by the one-time owner of a renowned, upscale pizzeria in the heart of Rockville Centre’s tony dining district, according to court documents and a three-month Advocate investigation. Their case dates back nearly 20 years, to 2003.

The employees came to the U.S. as undocumented immigrants from Latin America — five from El Salvador, two from Honduras and one from Mexico — to earn enough money to free their families from the endemic poverty that they endured back home, according to three of the workers. Seven had settled in Hempstead and one in Queens.

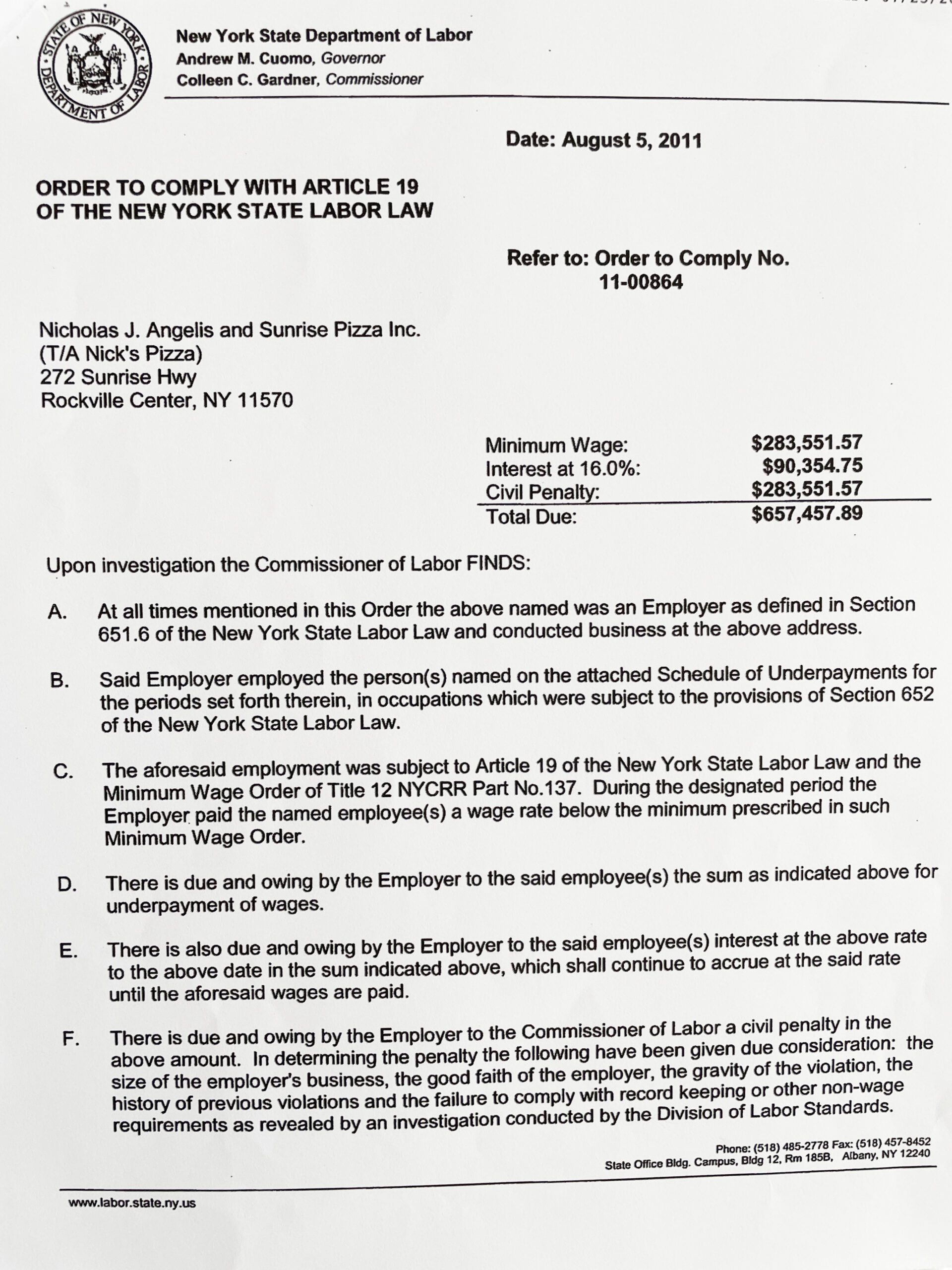

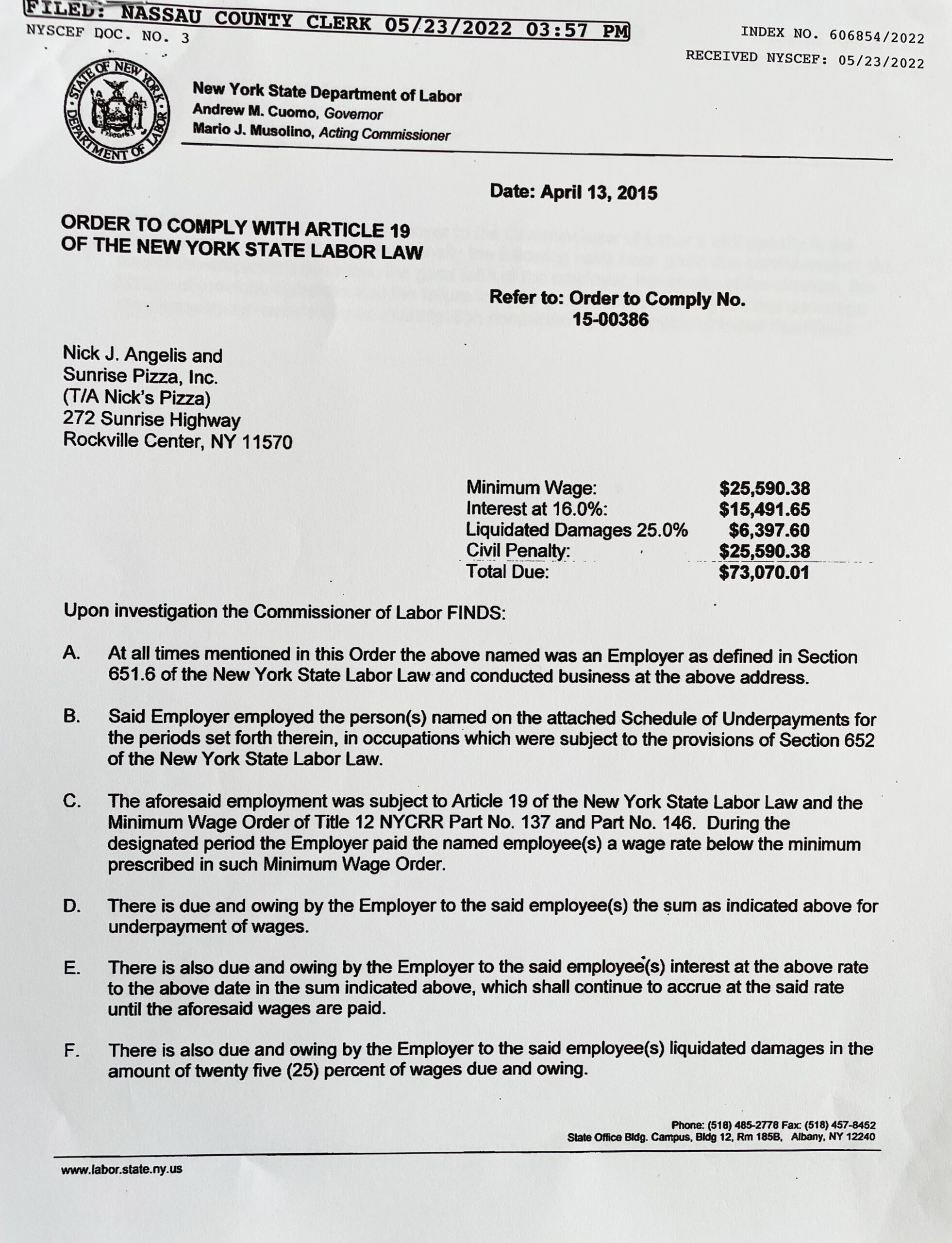

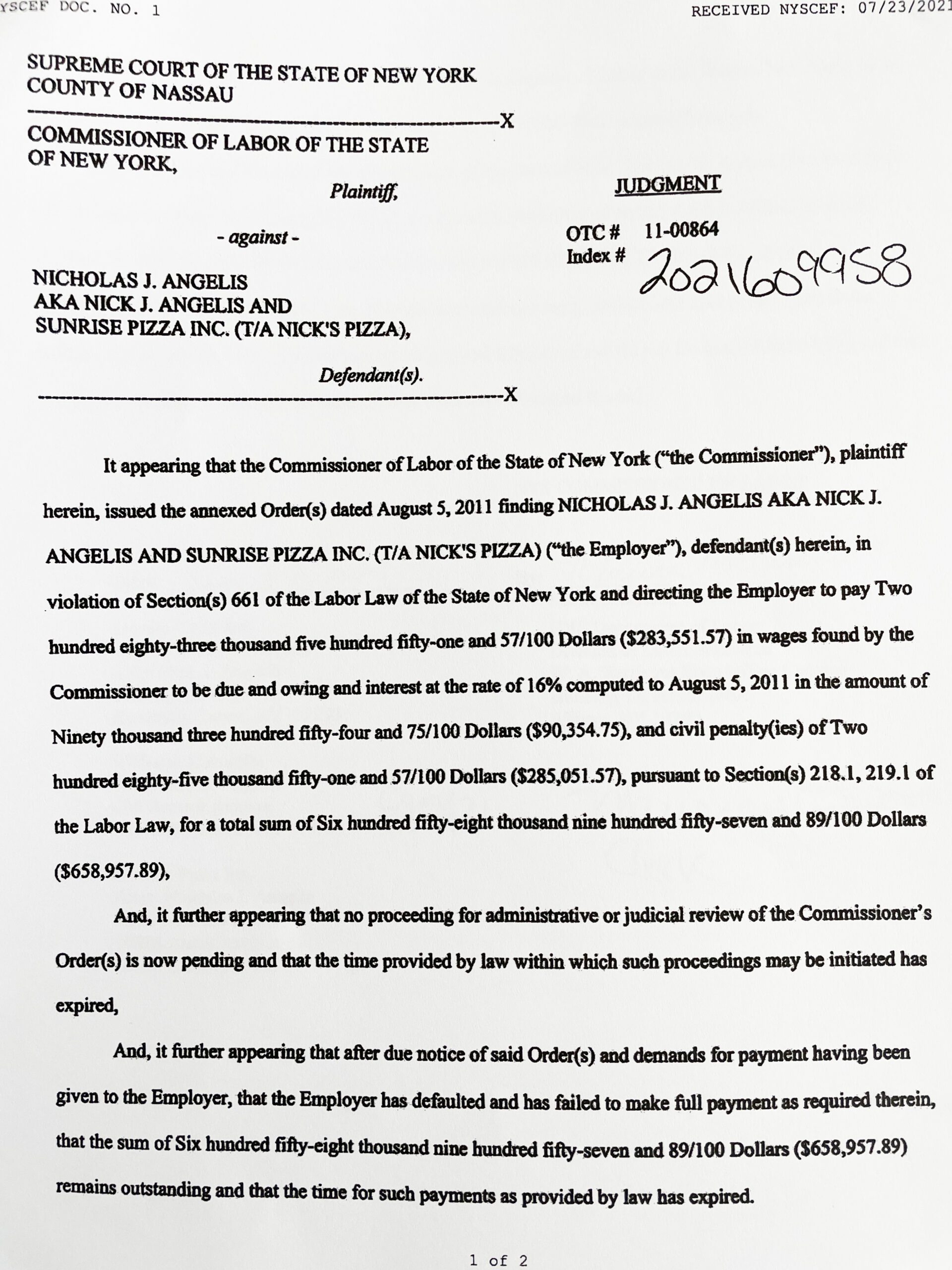

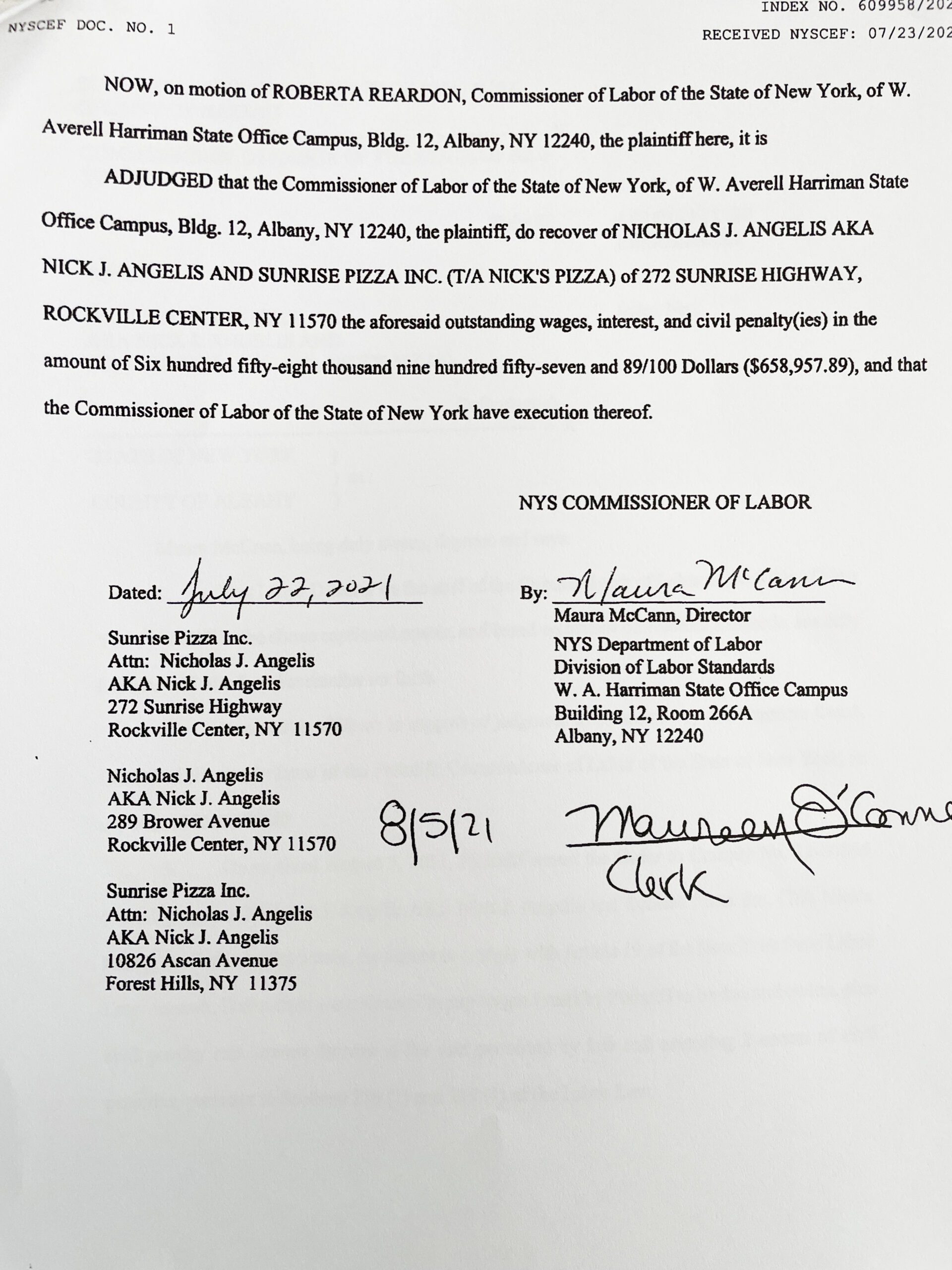

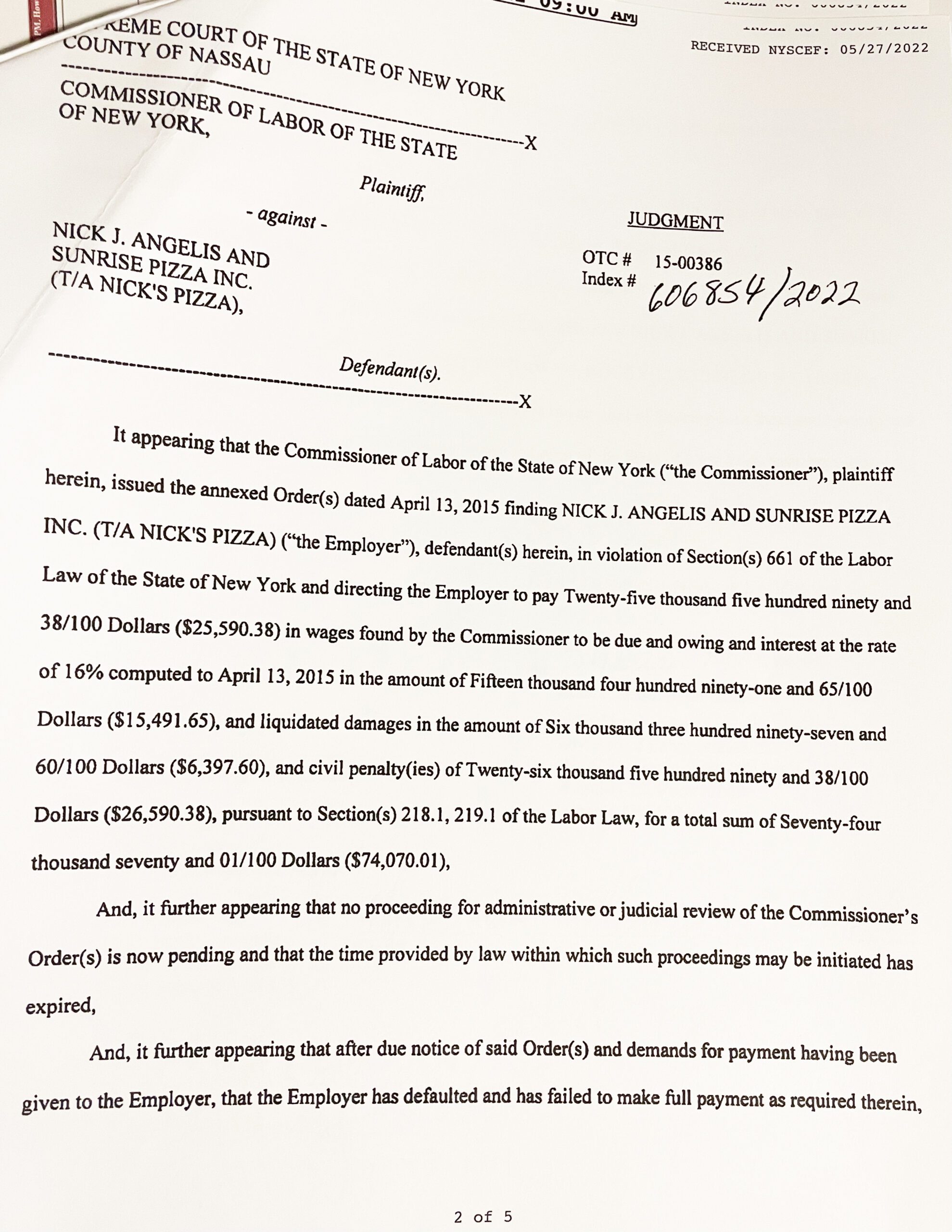

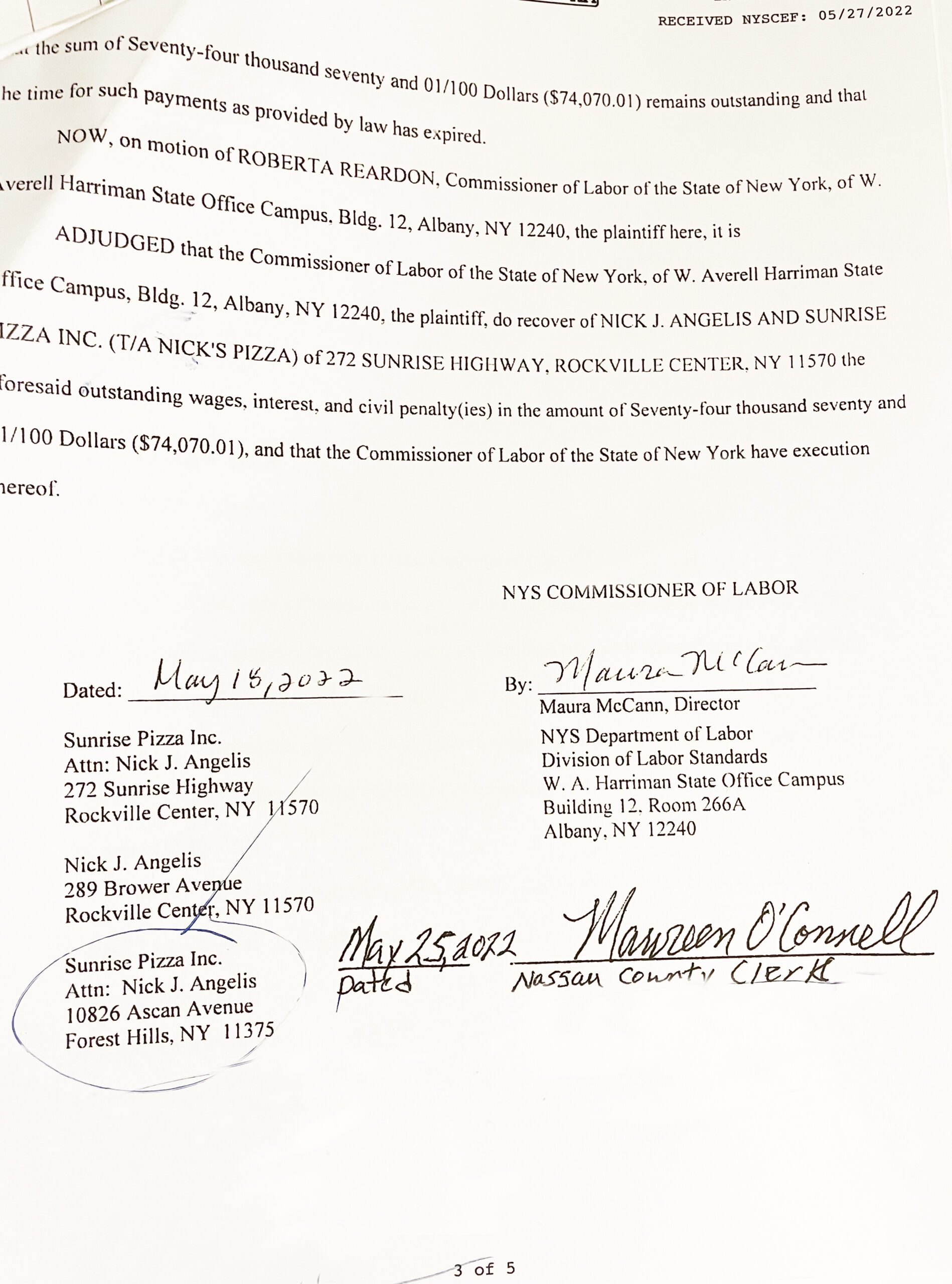

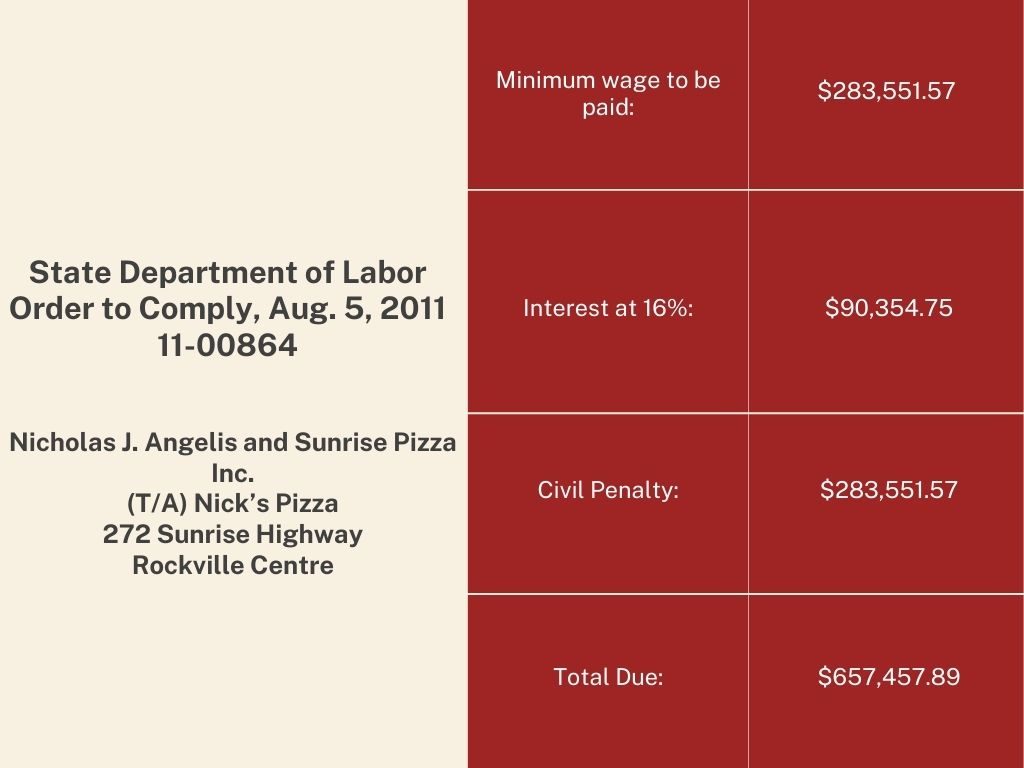

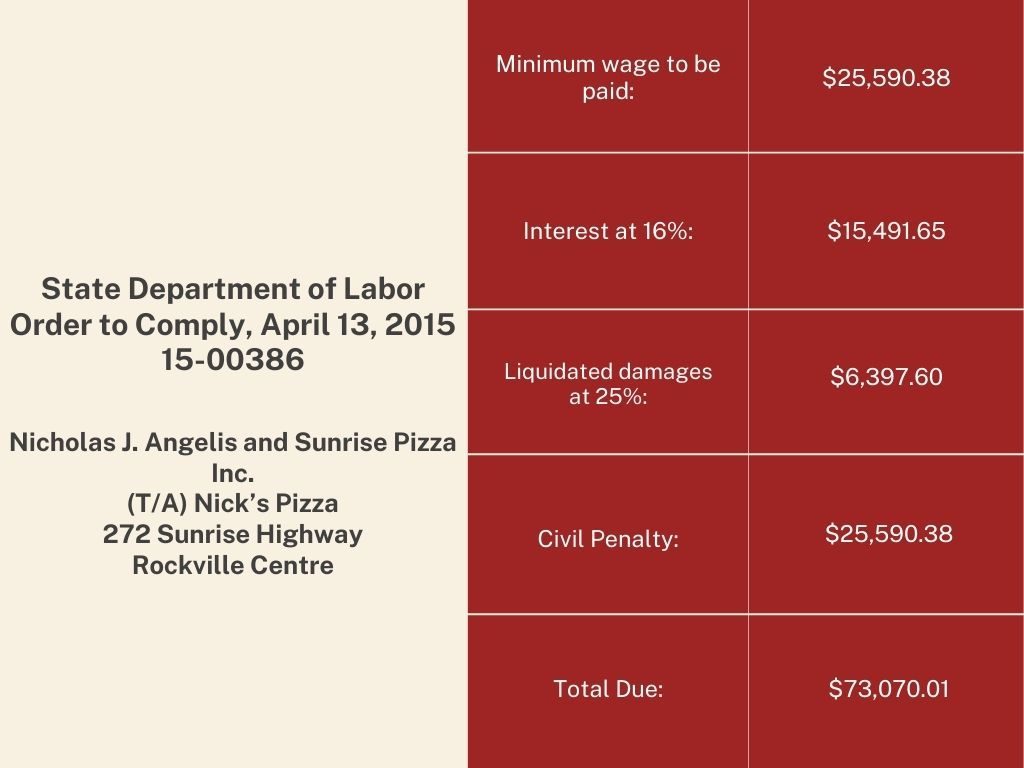

In 2011, the New York State Department of Labor ordered the then owner Nicholas J. Angelis and Nick’s Pizza to pay nearly $657,500 in back wages, interest, and penalties for underpaying workers between 2003 and 2009. A second order in 2015 added another $73,000.

All told, Angelis owes:

- $309,000-plus in unpaid wages to eight workers

- $106,000 in interest

- $6,400 in damages to one worker

- $311,500-plus in state civil penalties

Grand total: more than $733,000

Court filings show the men were consistently paid below New York’s minimum wage. Among the workers were a cook, a pizza maker, a food preparer, a kitchen helper, two salad makers and two dishwashers.

Payment of all back wages and penalties was supposed to have been made within 10 days of receipt of the orders. In the two sets of orders, Carmine Ruberto, the DOL’s Division of Labor Standards director, noted “the gravity of the violation” and a “history of previous violations.” An investigation by the Labor Standards Division revealed the violations, Ruberto wrote.

According to court records, no payments were ever made. As a result, the DOL secured the 2021 Supreme Court judgment on behalf of the eight workers in the 2011 case, requiring Angelis to pay, and then this May, a judgment in the 2015 case.

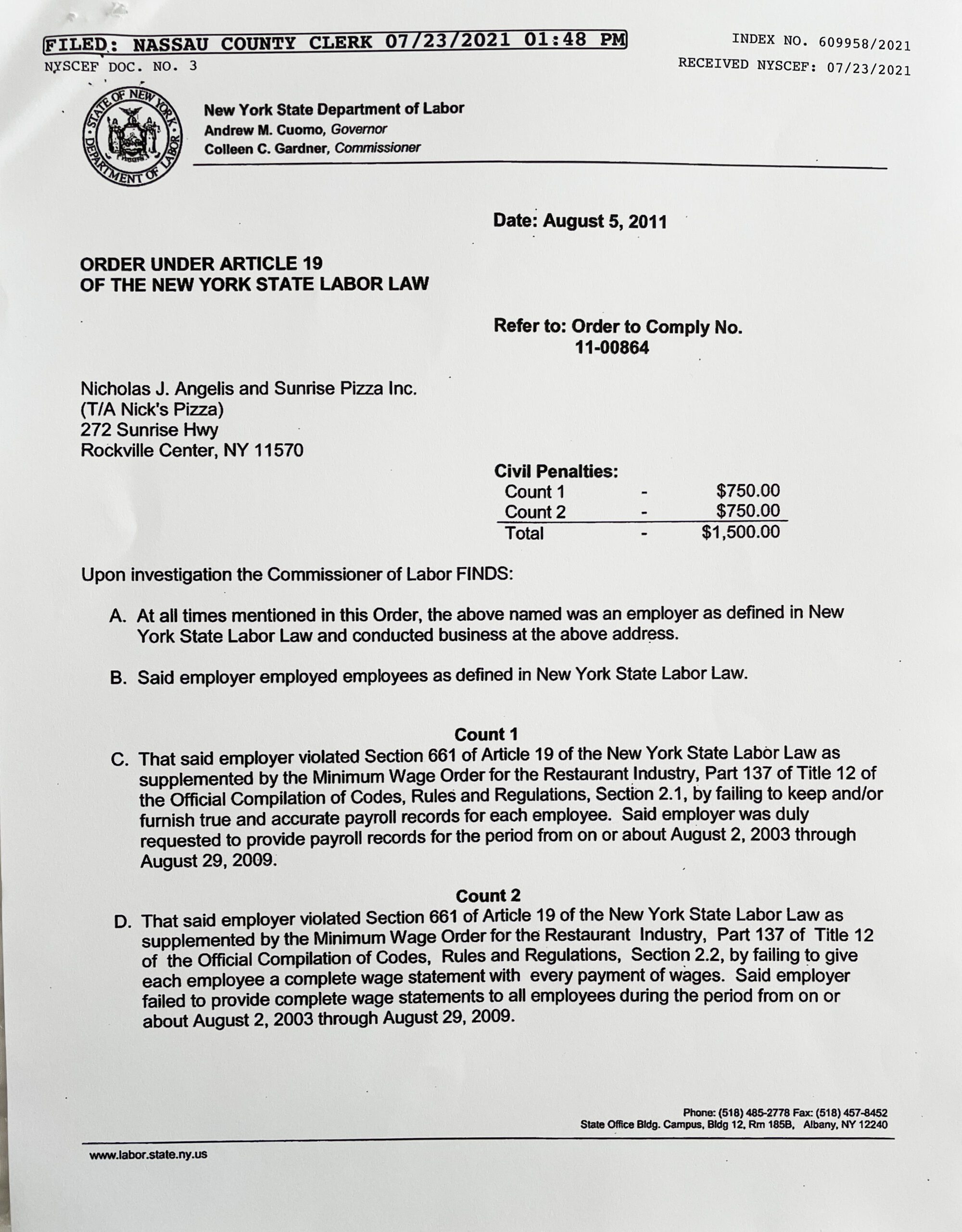

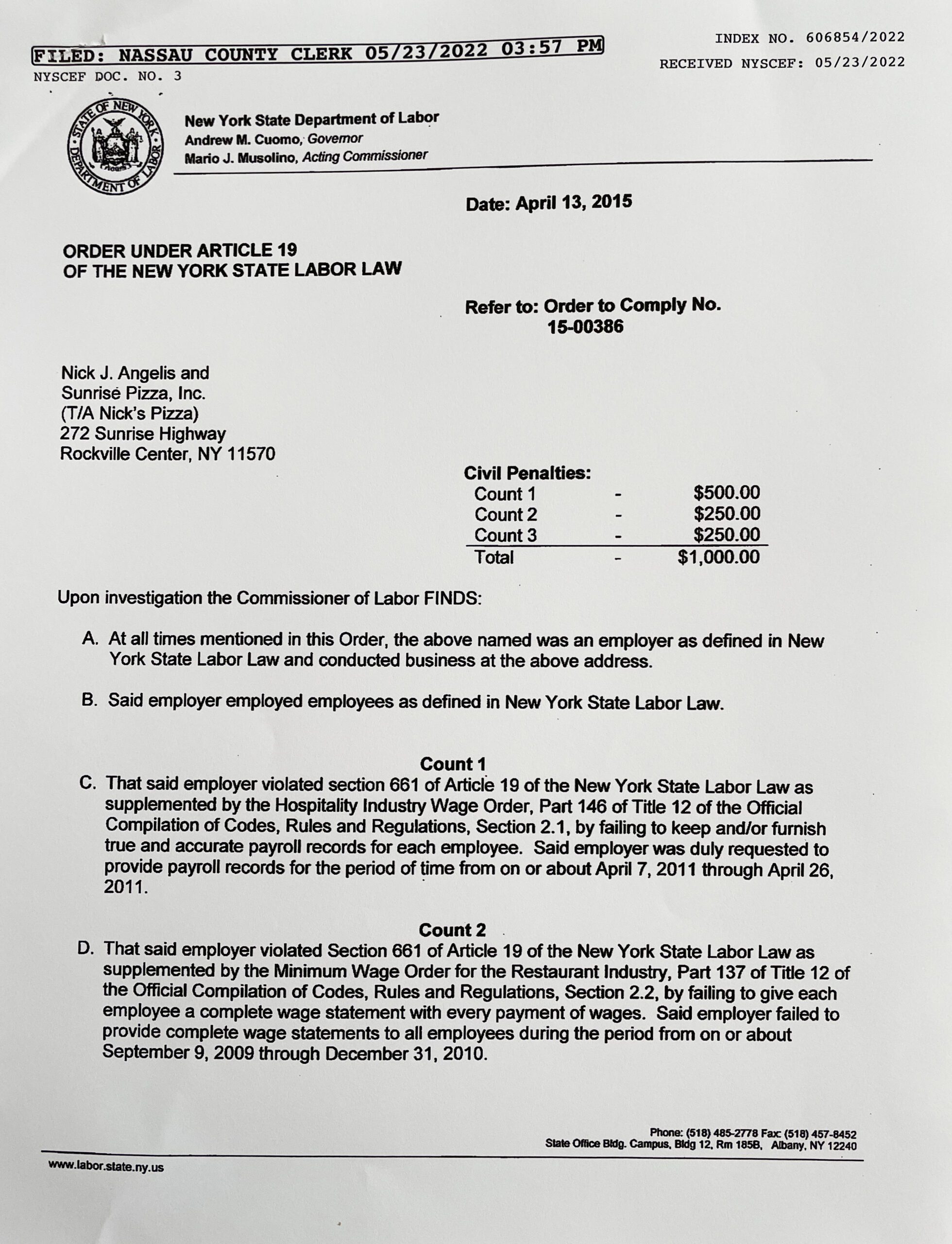

Both the orders to comply and judgments state Angelis and Nick’s Pizza violated Section 661 of state labor law, which requires all employers to “establish, maintain and preserve for not less than six years contemporaneous, true and accurate payroll records.”

Sections of the orders and the judgments can be found at the end of this story.

The workers first filed their complaint against Angelis and Nick’s Pizza 13 years ago. None are employed by Nick’s today, said Saul Asencio and Manuel Bernal, two of the workers.

In an email last week to The Long Island Advocate’s reporting partner, WABC-TV’s “Eyewitness News,” the DOL issued this statement for investigative reporter Kristin Thorne’s story: “We are actively working on this case and prepared to pursue all available measures to ensure these workers are paid what they are owed. Wage theft will not be tolerated.”

When reached recently by The Advocate for comment, Angelis said, “I don’t know what I’m supposed to do. I’m about making pizza.” He said he would contact his Manhattan-based attorney, Wayne Kreger, who might respond. Three messages left on Kreger’s voicemail were not returned.

“Wage theft will not be tolerated, and the DOL remains committed to protecting hardworking New Yorkers from bad actors who attempt to cheat them out of hard-earned wages.”

New York State Department of Labor Statement

The eight complainants did not know their cases had been won and they were each entitled to thousands of dollars in back wages until one of them received a letter from the DOL this March, Asencio said.

Tolerating it

According to the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, all hourly employees, regardless of immigration status, must at least be paid a state’s minimum wage, and are entitled to overtime pay (time and a half) if they work more than 40 hours a week. In fact, under federal law, undocumented workers can sue their employers for unpaid wages, as was the case in Kansas City, Mo., in 2013 when six unauthorized immigrant employees took the cafe owner whom they worked for to court — and won a nearly $441,000 judgment.

Asencio and Bernal, now 50 and 59, respectively, both said they put in 72 hours or more a week over six days at Nick’s Pizza. Asencio received a flat rate of $450 a week at the beginning, regardless of the number of hours worked, he said. After a period of years, he made $25 or $50 more a week as the cook. Bernal said he made $480 a week as a dishwasher and food preparer.

“They just tolerate it because they need the job,” Asencio said in Spanish. “They need the income. For all of us, it’s the only opportunity to satisfy our needs and attend to all the obligations.”

The two said they were paid in cash when they first started at Nick’s, and after eight months to a year, they received half their pay in cash and half by check. They rarely interacted with Angelis, who only stopped by on occasion to speak with them. They primarily dealt with the manager, who they remember regularly calling workers names like donkey, to imply “a lazy person,” and worse.

Nick’s Pizza payroll records, and the DOL’s investigation report, obtained through multiple Freedom of Information Law requests, confirmed the workers’ underpayment allegations.

For many of the kitchen workers, Nick’s was the first full-time job they found, usually through a friend, after making their way to the U.S. Most had fled their homelands and entered the U.S. without authorization, Asencio and Bernal said, to work and send cash back to their families, who might otherwise have gone hungry or been left homeless because there was no work to be had in their countries. They were desperate.

The eight workers started speaking out about their case on July 13th at an organizing meeting of immigrant laborers, held in the inconspicuous, sparsely furnished office of the Workplace Project, an immigrant workers’ rights group on Franklin Avenue in Hempstead. They were there to support the nationwide DALE (Deferred Action for Labor Enforcement) campaign, which calls for greater protections for undocumented workers and is coordinated by the Pasadena, Calif.-based National Day Laborer Organizing Network, a coalition of 66 member groups from across the country, including 12 in New York.

Manuel Oliva, now 43, a Salvadoran immigrant, is among the complainants against Nick’s Pizza. He spoke on behalf of the group at the meeting, in Spanish and English. He worked for four years as a salad maker at Nick’s and is now employed by a Valley Stream deli making sandwiches for minimum wage.

“We worked very hard for the money … I was happy just making a little living, a little sum of money, for my family back in El Salvador, so I didn’t pay no mind to what was going on,” said Oliva, who now makes his home in Stewart Manor with his wife and two children, ages 15 and 10.

Oliva recalled an incident in which the manager became physical with him. “In my own experience, they were not really polite,” he said of Nick’s management. “We just worked like animals. That’s why they were happy, I guess. We just did the work.”

Walking out

Asencio came to the U.S. in 1996, four years after the 12-year Salvadoran Civil War ended, when unemployment and inflation soared in his home country. He began work at Nick’s a year after his arrival on Long Island.

Bernal made the 3,400-mile trek from El Salvador to New York in 2002, a year after two massive earthquakes split his home in half, leaving a wide crack across the middle of his floor and up the walls. He, too, started at Nick’s about a year after he made it to the Island.

The earthquakes, which struck in January and February of 2001, caused “mass destruction” in Bernal’s village of Cuscatancingo, outside of San Salvador, the capital. Insurance paid nothing to repair his house, he said, because officials didn’t believe the structure would collapse. Then he lost his job at a bed factory. That’s when he decided to take a chance and come to the U.S.

“I needed to repair the house,” Bernal said in Spanish. “I needed to attend to my family’s needs.”

Asencio and Bernal were among those who sent half or more of their weekly pay back home to care for their families.

They said they knew from the start that Nick’s Pizza was underpaying them. When Asencio once asked for a higher wage after four or five years of work, he was told he could quit anytime because his replacement would be easily found. “A lot of people outside are looking for jobs,” he remembered the manager saying.

Asencio said he finally had had enough in 2009. It was a busy Friday, and the kitchen staff were in overdrive to keep up with a furious string of orders. Disliking the preparation of a dish, he said, a customer sent it back — twice — and the manager was furious, yelling as usual. Then he threw a wet towel at the back of the cook’s head.

Asencio teared up while recounting the incident.

The next day almost none of the kitchen workers showed up to Nick’s Pizza at their expected 10 a.m. start time, he said. Apologizing, the manager convinced them by phone to return at 2 p.m. They did. On the following Monday, they filed their state Department of Labor complaint.

Asencio lasted 16 years at the eatery, and Bernal, seven.

Collecting

what’s theirs

A U.S. Department of Labor official, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he is not permitted to talk with the media, said New York State law only allows authorities to recoup six years of back wages. In the Nick’s Pizza case, that meant the state DOL could only seek lost wages dating back to 2003, though some workers like Asencio had started at Nick’s years earlier than that.

Whether the workers will see any of the hundreds of thousands of dollars that they are owed remains to be seen. After winning the court judgments against Angelis and Nick’s Pizza, the DOL must seek to collect the funds owed to the workers and the state, said Karen P. Fernbach, a visiting professor at the Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University and former regional director of the National Labor Relations Board in Manhattan. “There is a whole process of collecting money judgments,” she said. How long that might take is uncertain.

Santos Morales, who now resides in Elmont and was a food preparer at Nick’s, received the letter from the DOL this past March, Asencio said. It was dated Aug. 10, 2021, and written in English, informing Morales that a judgment in the case had been won. The letter asked him to “please tell us if you know of any assets or bank accounts owned by your employer, which would help us try to collect the money they owe.”

It continued, “We will take steps to collect the money owed to you. However, if we cannot find their assets or bank accounts of your employer, we cannot collect.”

If the state were to secure any money, it would send it to Morales, the letter stated. “Otherwise,” it concluded in bold, italic type, “this is our final action in your case.” Heather Labunski, supervising labor standards investigator, signed it.

Asencio and Bernal said they never received such a letter. They would not have known the case had been won if Morales hadn’t called Asencio, who informed the rest of the workers.

“We will take steps to collect the money owed to you. However, if we cannot find their assets or bank accounts of your employer, we cannot collect.”

Heather Labunski, New York State Department of Labor

Both Asencio and Bernal said it would be a “blessing” to finally receive the tens of thousands of dollars in back wages that they are each owed, allowing them to pay off their debts and better provide for their families.

This case, Fernbach said, “is a perfect example of why we need immigration reform.” With a “path to citizenship, or at least legalization,” she said, undocumented workers would feel a greater sense of security about speaking up when faced with workplace abuses.

Some 10.5 million undocumented immigrants reside in the U.S. — nearly a quarter of all immigrants, according to the Washington, D.C.-based Pew Research Center. Roughly 100,000 are on Long Island.

An ongoing fight

The threat of deportation — whether overt or implicit — has long loomed large over many, if not most, undocumented workers, so they often say nothing about the abuses that they face.

Nadia Marin-Molina is co-executive director of the National Day Laborer Organizing Network (NDLON), where she has served in a variety of capacities for 12 years, including staff attorney. “In the past, we’ve seen that there’s been an imbalance where immigration status is used against workers who are trying to enforce their rights,” Marin-Molina said at the July organizing meeting. “It’s used to threaten workers to make sure they don’t file claims.”

In a three-page memorandum last Oct. 12th, Alejandro Mayorkas, the Cuban-born U.S. secretary of homeland security, directed Immigration and Customs Enforcement to develop plans to “mitigate the fear” of deportation that many undocumented workers feel when they consider reporting abuse by employers (see memo at the end of this story).

“Unscrupulous employers harm each worker competing for a job,” the memo read. “By exploiting undocumented workers and paying them substandard wages, the unscrupulous employers create an unfair labor market. They also unfairly drive down their costs and disadvantage their business competitors who abide by the law.”

A month later, in November 2021, the National Labor Relations Board offered further guidance in an 11-page memo penned by the agency’s general counsel, Jennifer Abruzzo, who noted that undocumented workers’ rights are protected under the National Labor Relations Act.

“In order for all workers to be able to exercise their rights under the act,” Abruzzo wrote, “we must zealously guard the right of immigrant workers to be free of immigration-related intimidation tactics that seek to silence employees.”

“Unscrupulous employers harm each worker competing for a job. By exploiting undocumented workers and paying them substandard wages, the unscrupulous employers create an unfair labor market.”

Alejandro Mayorkas, Secretary of Homeland Security

For eight months between November last year and this June, NDLON’s DALE (Deferred Action for Immigration Enforcement) campaign called on the Biden administration to offer greater protections for undocumented workers who report workplace exploitation, including deferred action, which would allow them to remain in the U.S. and continue working while their cases are adjudicated. Among other measures, NDLON formed a Blue Ribbon Commission comprising workers and immigrant-rights groups, which organized demonstrations and public hearings, including one in Washington, D.C.

An integral part of the U.S. workforce

According to the Pew Research Center in Washington, D.C., undocumented immigrants represented 5% of the U.S. civilian workforce in 2014, including 9% of all service jobs. About a third of unauthorized workers are employed in the service industry, compared with 17% of U.S.-born workers.

According to Pew, undocumented workers account for:

- 20% of cooking machine operators.

- 19% of dishwashers.

- 18% of butchers.

- 16% of cooks.

- 14% of bakers.

- 14% of dining room attendants and bartenders.

- 13% of chefs and head cooks.

- 12% of food preparers.

––Madeline Armstrong, Long Island Advocate

On July 6th, the U.S. Department of Labor announced a memorandum of understanding with the Department of Homeland Security, allowing undocumented workers who report abuses to seek deferred action under what officials call “prosecutorial discretion.”

For the federal DOL “to effectuate the laws under its jurisdiction, regardless of immigration status,” a department FAQ sheet reads, “workers must feel free to participate in … investigations and proceedings without fear of retaliation or immigration-related consequences.”

The Department of Homeland Security decides whether to grant prosecutorial discretion, though the DOL can offer a statement of support to an individual. It is granted on a case-by-case basis, according to the DOL. A temporary measure that could change with a new administration, it also does not confer lawful status, nor does it provide a path to legal residence or citizenship.

Still, it does, for now, provide greater protection for undocumented workers, and that is why NDLON is working to get the word out to them about the new policy through meetings like the one in July.

The acronym DALE has two meanings. In addition to Deferred Action for Labor Enforcement, it can also stand for Desde Abajo Labor Enforcement, or Labor Enforcement from Below — that is, at the workers’ level, Marin-Molina explained.

Labor enforcement agencies, she said, “really need workers to be their eyes and ears … They rely on them as witnesses.”

“We’re here, and we’re going to keep fighting for the other workers who don’t know what to do, who are in a limbo,” Oliva said of the eight Nick’s Pizza employees in July.

Miguel Alas Sevillano, the Workplace Project’s assistant director, said workers come to the nonprofit agency every week seeking help to fight for wages that they are owed. “Their human rights, their dignity, their human dignity, must be observed,” he said.

Current Workplace Project Executive Director Lilliam Juarez said the Nick’s Pizza case is unusual because the amounts owed are large, but many immigrant workers are owed $3,000 to $10,000 by their employers, and they, too, struggle to collect.

Government officials, Juarez said, must enforce workers’ rights. “If they can’t enforce them,” she noted in Spanish, “it’s as if they don’t exist.”