By Alexandra Whitbeck

Editor’s note: Certain names within this story have been changed to protect their identities.

James McHugh started using marijuana, alcohol, and cigarettes with his older brother and friends when he was 12 years old, and at 26, he still has not given up these habits. Dropping out of school in 10th grade in 2009, he left his mother’s home at 15 to work odd jobs throughout his teenage years to support himself, and his drug use.

He wasn’t interested in school, and he wanted to earn money to buy his freedom. Experimenting with drugs was another alluring factor in his decision to drop out and leave home. His parents resisted his choice, but he was tenacious, and they knew he would do it, whether or not he was granted permission.

Once on his own, McHugh began to dabble further in drugs, laughingly saying, “It’s easier to tell you what I haven’t done.” Among the drugs that he has abused are fentanyl, oxycodone and crack cocaine, with a smattering of other substances in between.

The opioid crisis

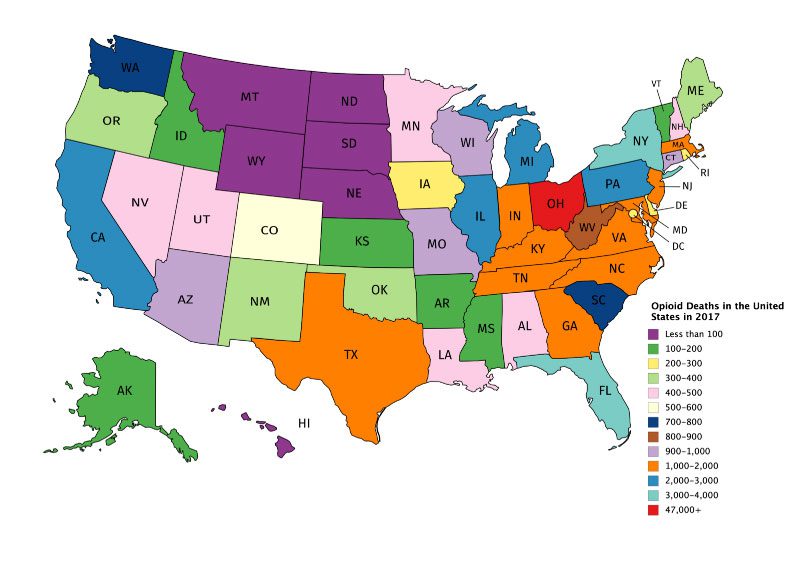

Opioids like fentanyl and oxycodone have killed more than 700,000 people across the United States since 1999, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid use in the U.S. surged over the past two decades owing to a push by pharmaceutical companies and physicians that began in the 1990s under the mistaken belief that the painkillers were non-addictive.

It is now clear that opioids are highly addictive, and have a long-term impact on the academic and social life of children when they are exposed to substance use at a young age. “Addiction to prescription pain medications has had devastating effect on families,” wrote Dr. April Dirks, an associate professor of social work at Mount Mercy University in Iowa, in her article, “The Opioid Epidemic: Impact on Children and Families,” which appeared in the Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders in 2018.

Children are forced to grow up in and learn from the environment they are given. If their home life is filled with drug use, the trajectory for their adult life may follow suit. People who are exposed to illicit familial drug use during adolescence are at an increased risk of drug use later in life and can develop pre-conceived concepts about the normality of drugs. The American Addiction Center states, “In homes where one or more adults abuse alcohol or drugs, children are approximately twice as likely to develop addictive disorders themselves.”

At 16, McHugh got his opioids from street dealers, or he stole bottles of pills from local supermarkets and his stepmother’s medicine cabinet. He met dealers through his brother and worked as a golf caddy and a shoe shiner, and was employed at a pizza shop, to obtain money to support his drug abuse.

Due to his close relationship with his brother, who introduced him to drugs, and the frequent use of pain relievers by his stepmother, drugs seemed normal to McHugh. He began using at a young age because drugs were prevalent in his life and accessible.

McHugh, who grew up in rural upstate New York, said he found life there boring. He joked about how there is nothing to do up there but drugs. The opioid crisis affects communities across the nation, particularly striking small towns like the one where McHugh grew up. Albany County saw a 71 percent rise in chronic drug use and overdoses from 2010 and 2015, according to the Addiction Center in Albany.

Long Island is experiencing high rates of opioid use, with CBS Local estimating that more than 45,000 people here were addicted to opioids in 2019. In Nassau County alone, 1,300 have died due to the opioid crisis since 2010.

The American Academy for Pediatrics projects that 8.7 million children under 18 in the U.S. have a parent who suffers from a substance abuse disorder. That’s roughly 12 percent of the 74 million children living in this country.

The effect on children

What happens to the children who are separated from a parent who has a substance abuse disorder? More often than not they are relocated into state childcare systems. There is a correlation between rates of children in foster care and periods of high opioid deaths. The American Psychological Association identifies “the increase in demand for foster care comes at a time when opioid deaths have surged,” resulting in children being “indirect victims of the crisis.” The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a 2016 report that child placement in foster care systems is increasing due to parental opioid use.

Mothers are one of the highest concerns in the opioid crisis. Women are becoming addicted to opioids more rapidly than men, according to Suzanne C. Brundage and Carol Levine in “The Ripple Effect: The Impact of the Opioid Epidemic on Children and Families.” Brundage and Levine discuss the effects on pregnant women, specifically as “both SUD [substance abuse disorder] treatment facilities and women’s health providers are, in general, under-equipped to care for pregnant women and mothers with SUD’s.” The Children’s Defense Fund found that between 14 to 22 percent of pregnant women fill an opioid prescription nationwide.

Infants suffering from opioid withdrawal face a variety of medical issues, perhaps throughout their lives. Dirks discusses in her article the increasing number of babies born to opioid-addicted mothers. If during her pregnancy, the woman used prescription or non-prescription opioids, there is a potential for the baby to suffer from neonatal abstinence syndrome, which can result in birth defects and withdrawal symptoms at birth. Depending on the severity of the mother’s opioid use, the infant may develop long-term delays and learning disabilities.

Dr. Jeffrey Reynolds, president of the Family and Children’s Association in Mineola, said, “By virtue of having a parent who’s addicted, they’re exponentially more likely to develop an addiction over the course of their lifetime.” Reynolds identifies children between the ages of 5 and 12 who have addicted parents.

The FCA is tackling issues that face the children of Nassau County through treatment facilities, recovery centers and mental health programs at 10 locations. The programs are helping traumatized children cope within the opioid crisis and many other issues present in their lives.

Within the mental health programs offered, FCA reaches out to those affected by the opioid crisis through concerned family members, as the organization is active in the community and reachable.

Reynolds believes “the thing about the opioid crisis is it forces us to work together.” This is seen in the organization’s involvement with the North Shore Child Family Guidance in Roslyn and Central Nassau Counseling and Guidance Services in Hicksville. Organizations like these are collaborating on the best avenue of recovery, treatment and therapy.

The FCA also operates shelters. A safe house in Wantagh called The Haven provides beds for abandoned and runaway children fleeing homes ravaged by opioids and unstable environments. The Haven houses up to 12 children, and typically has each room filled.

Reynolds and the FCA are currently conducting research into the siblings of opioid users. Reynolds is looking to focus on the child who may not be using, but is affected by the levels of attention given by parents to the child who is abusing drugs.

“I worry that the needs of these kids are going unidentified and unmet,” said Reynolds, who said children can be swept up in their siblings’ drug use, as McHugh was as a teenager.

The FCA has aided roughly 10,000 children in both Nassau and Suffolk counties, as “kids are the heart and soul of what we do,” Reynolds said.

The FCA also seeks to prevent drug use. Teaching children about the dangers of drug abuse is key.

The Bellmore-Merrick Central High School District has informational programs that are intended to prevent drug abuse. From 2014 to 2017, the leading cause of death was overdose in people ages 18 to 35 years old, according to the Nassau County Health Assessment Report, so discussing the dangers of opioids is essential for schools.

The district works closely with Wendy Tepfer, director of the Community Parent Center, which is located in the BMCSHD’s main office in North Merrick. The organization teaches Bellmore-Merrick students in grades seven to 12 about drug use. It brings guest speakers into the classrooms to discuss the dangers of abusing opioids, among many other drugs.

The Parent Center is part of a coalition of local organizations working to stop drug abuse among young people, according to Eric Caballero, the director of physical education, athletics, driver education and health for the Central District. The coalition comprises school district staff, lawmakers, emergency service personnel and local residents, all working “to ensure that we are providing the type of information our community needs to be aware of,” Caballero said.

In making this information universal for all ages, he said, “Members of our component districts that also attend the coalition meetings are able to turnkey that.” Among the component districts are the Bellmore, Merrick, North Bellmore and North Merrick elementary districts.

BMCHSD staff are trained annually in administering Narcan, an opioid antagonist that can reverse the effects of an overdose; however, the district has never had to use it, officials said.

There is also a yearly Drug Take-back Day in October, sponsored by Nassau County, the BMCHSD and the Parent Center, at which unused medications and sharps are collected for proper disposal by Nassau County police.

McHugh’s story

McHugh’s high school did not have such preventive programs, he said. He was navigating the newly introduced world of drugs at 16. He was using a variety of drugs at a steady rate until he was 19, and the severity of use kept increasing.

“If him and I didn’t start dating, he would be dead,” said his girlfriend of six years, Kelly. “He was really bad.”

McHugh was doing cocaine and taking painkillers, all while drinking.

“I think what woke him up was when we almost died,” Kelly said. James was 19 and drunk, driving 120 mph when he flipped his car. Kelly was a passenger in the car. She broke vertebrae in her back.

McHugh now lives with Kelly and her two daughter upstate. He is opioid-free, but not entirely drug-free.