By Jillian Tkaczyk

Editor’s note: Part two in a series looking at segregation on Long Island.

“Hempstead? No, you don’t want to go there . . . You don’t want to see houses there.”

These were the words that a realtor reportedly told Jessica Mannhaupt, a Hofstra University publishing studies major from Massapequa Park who graduated in May, when she was looking for off-campus rental houses while still a student.

“It was a little strange,” Mannhaupt said. “I wanted to keep my options open and didn’t plan to lock myself into one area. The realtor put up a fight to show mainly houses in Garden City, as he said they were ‘better than what I’d find in Hempstead.’”

“The realtor put up a fight to show mainly houses in Garden City, as he said they were ‘better than what I’d find in Hempstead.’”

Jessica Mannhaput, Hofstra student

Mannhaupt said she had no preference between the two villages, noting that renting in Hempstead would be more budget-friendly for her, yet the realtor appeared reluctant to tour listings in Hempstead.

The realtor may have been trying to “steer” Mannhaupt, who is white, away from the racially diverse Hempstead, where Hofstra is located, to the nearly all-white Garden City nearby. Steering is, experts say, one way that real estate agencies continue “redlining” communities, or cordoning them off by race.

During the 1930s, banks drew red lines on maps around communities of color to delineate them as “hazardous” and at “high risk” of defaulting on their loans, often simply because people were not white, and then the banks would deny people there home loans because they were considered “high risk,” according to The Washington Post. The practice was among the key factors that perpetuated segregated neighborhoods, particularly in suburban regions like Long Island, forcing people of color to stay put in their neighborhoods when they might have wanted to move out and on. Home ownership, a key to wealth building, was often denied to people of color, and communities of color have yet to build the levels of home equity seen in largely white communities today.

And segregated communities persist today.

Redlining was outlawed in the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968, but the practice continues in more subtle ways today, including racial steering by real estate agencies. Federal regulators, though, are considering the first changes to the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 in decades, with the aim of increasing home lending to people of color, which would afford them a greater ability to buy into the neighborhoods of their choice, according to a May 5 article on the CNBC website.

“The CRA is one of our most important tools to improve financial inclusion in communities across America, so it is critical to get reform right,” said Lael Brainard, the Federal Reserve Board vice chair.

Big banks, however, are pushing back, saying any changes to the CRA could increase lending costs.

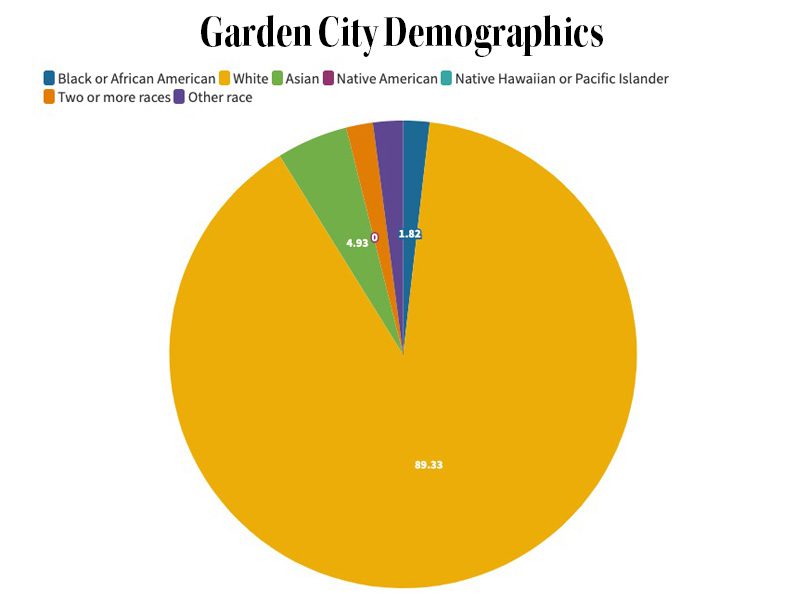

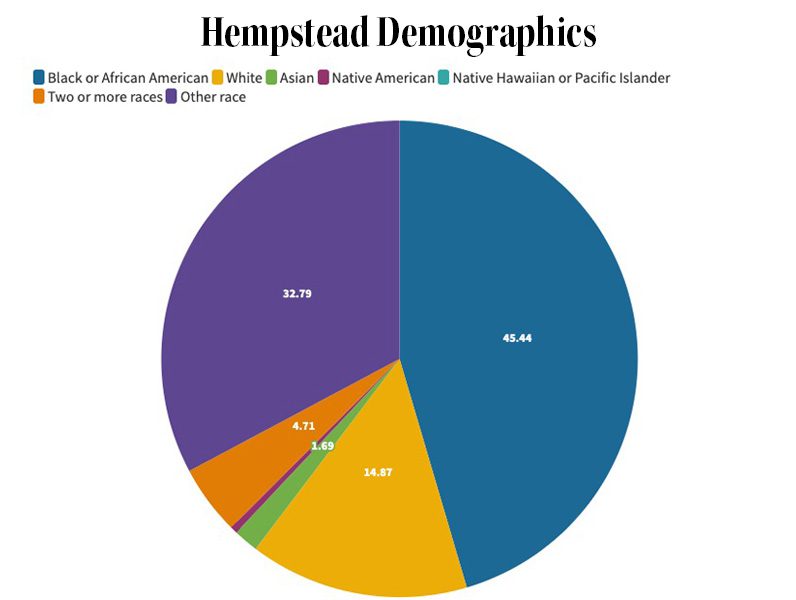

Garden City and Hempstead, two villages that sit side by side to each other, illustrate just how segregated Long Island remains. Garden City, with a population of about 22,400, is 89% white, 2% Black and 9% other, according to census data. Hempstead, with a population of nearly 59,000 people, is around 45% Black, 33% Hispanic, 15% white and 7% other.

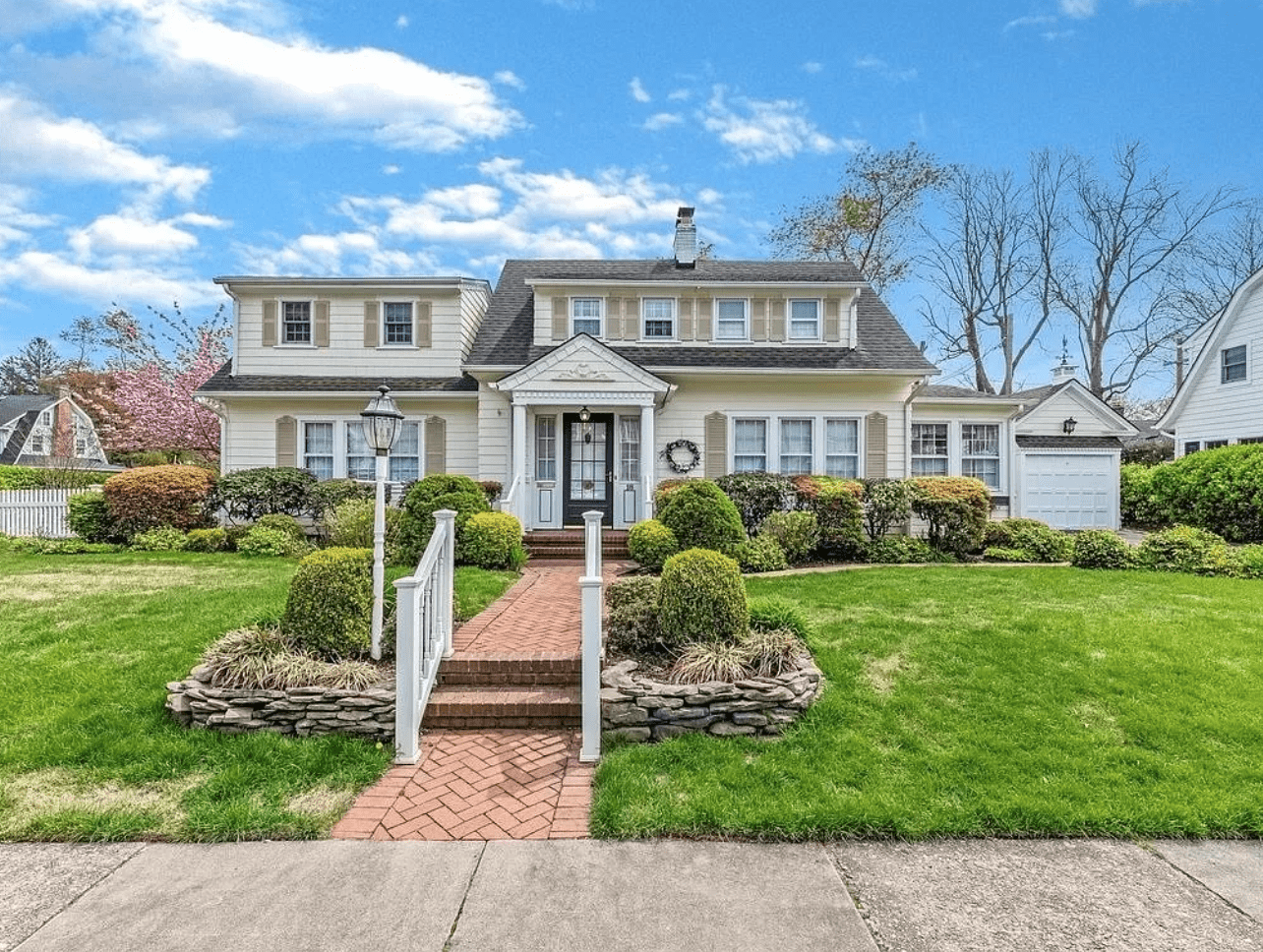

Home values are significantly higher in Garden City, according to a Zillow search of local properties. A recent quick search of homes for sale in the village yielded several large homes with green lawns and built-in garages. The majority of the houses’ exteriors were recently done. Most homes went for more than $1 million, with a few in the $800,000 to $900,000 range.

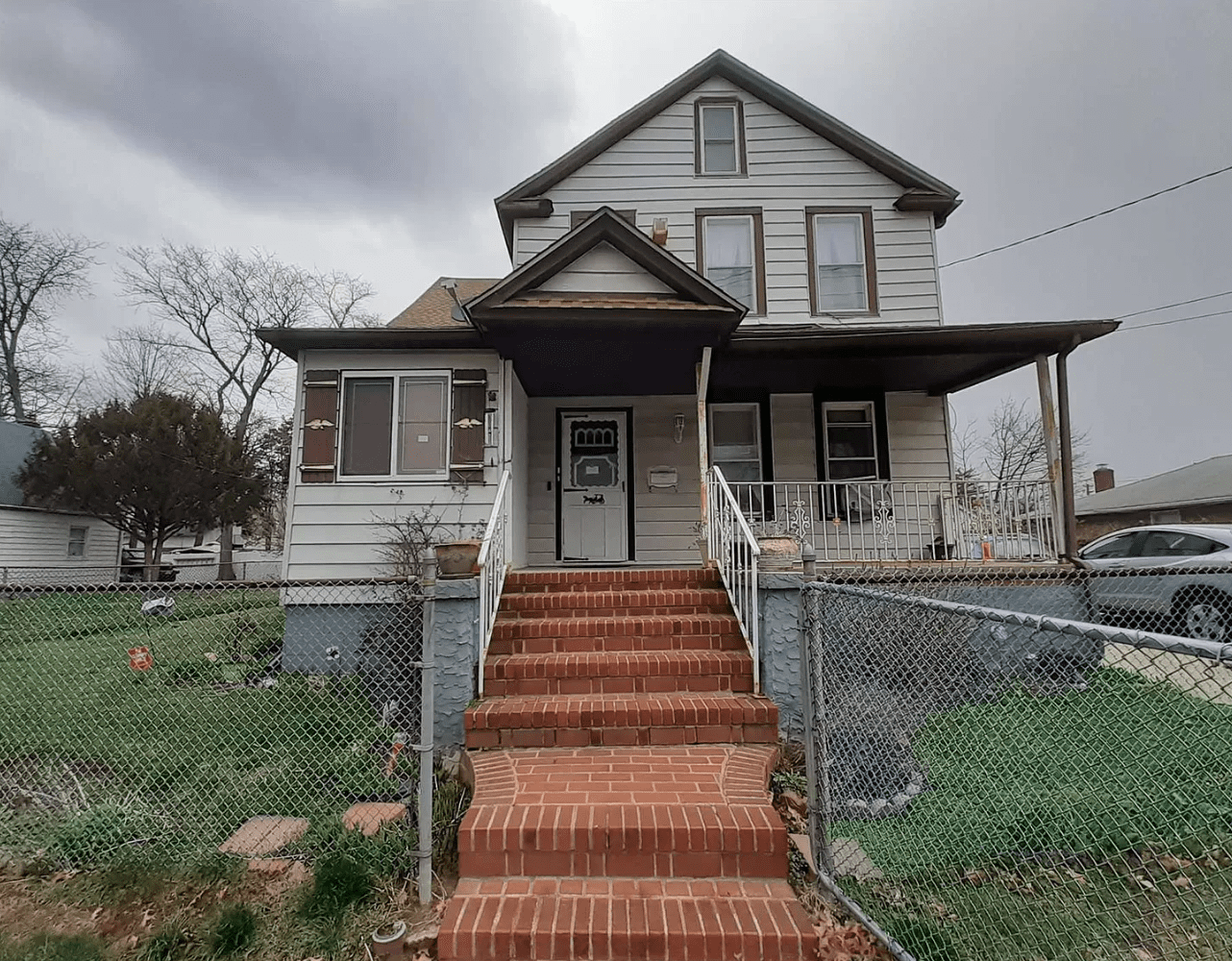

A search of houses for sale in Hempstead yielded many single-story houses, with the median price in the $300,000 to $400,000 range.

The average cost to rent a three- to four-bedroom house in Garden City was around $5,000, compared to Hempstead’s $3,000 per month.

Hofstra University student Gina Laramore-Jones had a similar experience as Mannhaupt when she was hunting for a house to rent this past spring for the fall semester.

“A realtor showed us a big house in Garden City that had just been built the year prior,” Laramore-Jones said. “It felt really luxurious, and they even mentioned monthly maid services included in the rent.”

Laramore-Jones, who is white, noted a pattern in the showings — those shown in Garden City were considerably larger or recently built, while those in Hempstead were less maintained.

The realtor commented how Laramore-Jones and her roommates were less likely to damage the house because they were women, but if they wanted a party house that could be torn up, they should choose Hempstead.

“What really shocked me was how transparent the realtor was about the difference between the villages,” Laramore-Jones said. “He plainly told us that this was a nice, new home, not a ‘party house.’ He pointed in the direction of Hempstead and said he had houses there that we could tear up.”

“He plainly told us that this was a nice, new home, not a ‘party house.’ He pointed in the direction of Hempstead and said he had houses there that we could tear up.”

Gina Laramore-Jones, Hofstra student

Seven Garden City and Hempstead real estate agents called by The Advocate declined to comment for this story or hung up.

Another key difference between housing in Garden City and Hempstead is the number of affordable-housing complexes in each of the communities — Garden City has but one, while Hempstead has 19, the most in Nassau County. And there are plans to increase the number of affordable complexes in Hempstead. The Carman Place project and the Estella Housing project, located across the street from each other, are currently in the works. Combined, they will add 324 affordable units to the area.

Ralph Fasano, of Concern for Independent Living, one of the developers constructing the Estella, told Newsday that building affordable units “is the right thing to do, and eventually, you find a way to do it, even when sometimes it takes elections to change things.”

Beyond affordable housing, Hempstead officials are looking to increase the village’s stock of market-rate housing. Speaking at the Long Island Smart Growth Awards in Woodbury June 10, at which the Estella project was honored, Hempstead Mayor Waylyn Hobbs Jr. said, “We’re looking for market rate . . . We love granite top, too.”

Scott Brinton contributed to this story.