By Sarah Ng

Walking into a classroom, students can be seen staring intently into the bright light of the computer screens that illuminate their faces, with the faint sound of fingers tapping keyboards in the background. It is a common scene in an education setting, but these students are using ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence chatbot, to answer questions. This is learning in the digital age.

“I don’t mind it. I embrace it,” said Roberto Joseph, an associate professor of teaching, learning and technology at Hofstra University, on the inclusion of technology in the learning space.

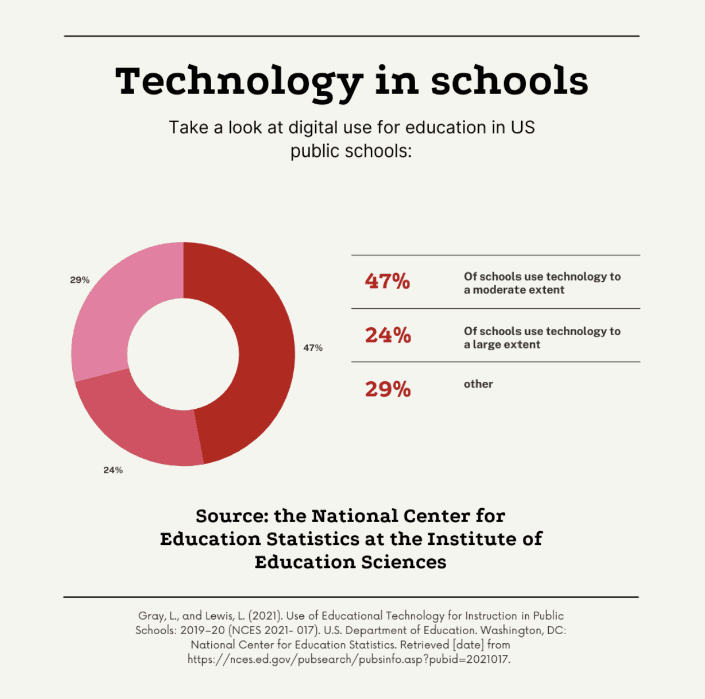

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, a 2020 survey of 1,300 public schools in 50 states found that 70% made regular use of technology in the classroom. Of those, 47% of respondents said they used technology to a moderate extent and 24% to a large extent.

Artificial intelligence platforms like ChatGPT, once the domain of computer engineering labs, are now readily available to the public. The use of ChatGPT poses a problem for academic integrity, as students can submit the answers that the language-based chatbot gives them for their homework assignments, including whole essays.

“There are a lot of kids who abuse AI a lot,” said Yvani Lopez, a senior at Uniondale High School. “People use [AI] as an excuse to go on their phones.” And, Lopez said, they “lie” about their assignments.

Some students are against the use of this technology, saying it hinders learning. “It feels weird because we’re paying for an education and then you’re using that,” said Madison Turner, a sophomore speech, language and hearing sciences major at Hofstra. “I think some people rely on it too much.”

Before the pandemic, technology “was not supplemental; it was adding” to the student learning experience, Turner said. “I think [AI] will be beneficial in certain aspects . . . as long as it is meant to support what we’re actually doing in the classroom.”

But, Turner quickly added, “When it’s replacing a teacher teaching or replacing collaborating with people, I think that could be more harmful.”

Technology is “moving us in a way that we may not be ready for… but now is the time to get ready for it,” Joseph said. “We need to be asking better questions, higher-order thinking questions.”

The professor noted that AI does not answer “why” or “how” questions, but rather provides basic facts. Educators thus must frame their questions in more complex ways to elicit deeper responses, developing critical-thinking skills.

With platforms such as the trivia competitions Kahoot and Nearpod, there has also been a “gameification” of education, which may soon be incorporated into AI chatbots, Joseph said, adding, “It’s another tool in the teaching arsenal.”

“ChatGPT doesn’t have to be our enemy,” said Janice Koch, Hofstra University professor emerita of curriculum and teaching. “Technology can be a very exciting tool for learning. It can give students different points of view, but most importantly we want them to have the capacity to determine what is good evidence. How do we know what we know?”

Koch said technology offers “simulations, modeling [and] augmented reality” to “enhance understanding,” including modeling what is too small for the eye to detect, like a DNA molecule.

Technology is “moving us in a way that we may not be ready for… but now is the time to get ready for it.”

Roberto Joseph, Hofstra University Professor of Teaching, Learning and Technology

William Cheung, a sophomore chemistry major at Hofstra, said he uses ChatGPT to figure out what he does not know about a subject, and then he finds an expert with whom he can discuss a topic to dig deeper. ChatGPT “can make up for deficiencies in terms of vocabulary,” he said.

He also said the writing produced by ChatGPT is “not that good” compared with student writing.

“I feel like [AI] is way better for social studies and English,” said Lopez, who prefers to visualize and learn math away from the screen.

AI can also help with digital literacy. “You can take from [technology] instead of using it directly” and learn about the limitations of AI, said Raul Moran, a freshman at Uniondale High School.

The coronavirus pandemic highlighted the need for technology to be accessible for all students who might be learning remotely. According to the nonpartisan, Washington, D.C.-based Pew Research Center, 20% of parents said it was very or somewhat likely that their children did not complete schoolwork during the pandemic because they lacked access to a computer.

“We’re always going to have an access issue, as long as you come out with something new,” Joseph said. “We’re always going to be talking about digital divide until the school district puts their money where the technology is.”

During the pandemic, “parents that live in poorer neighborhoods would take their students to parking lots in Walmart or Target just to get their Wi-Fi because they could not afford broadband access,” said Koch, who also noted that not all students returned to school after the pandemic.

“We have to level the playing field . . . We need access for all students,” she said, proposing the need to improve internet infrastructure along with providing devices to remedy the digital divide.

Whether ChatGPT will put teachers’ jobs in jeopardy, Koch said, “Even though you can certainly have relationships with chatbots, in teaching and learning, the relationship you have with the teacher, the exchange of ideas, is paramount and very important. I don’t think AI can substitute for that.”