By Charles Shaw

Editor’s note: The following story was written as part of the graduate-level Advocacy Journalism class.

Last December, the New York City Health Department reported that the first two Overdose Prevention Centers operated by OnePoint NYC had prevented 59 deaths in their first three weeks, and that the centers had been used more than 2,000 times in that time, showing promising results for such harm-reduction programs.

Harm reduction is a set of principles and practices aimed at reducing the risks associated with drug use. It includes access to sterile syringes, fentanyl test strips and naloxone, a medicine capable of immediately reversing an opioid overdose.

These services could benefit Suffolk County, which will receive $26 million from New York’s legal settlement with opioid makers, with more funding arriving in the future, according to a statement by New York State Attorney General Letitia James. Task forces were formed in the county to determine where the money will be spent, including education, prevention, drug treatment and intervention. The exact details of where the money will go and how it will be spent remain vague, but harm reduction should be considered for funding, experts say.

“The deaths on Long Island have really cut through any stereotype that people may have had about who is at risk or who is affected.”

Tina Wolf, Executive Director, Community Action for Social Justice

“The deaths on Long Island have really cut through any stereotype that people may have had about who is at risk or who is affected,” said Tina Wolf, executive director and co-founder of Community Action for Social Justice, a not-for-profit that has been Long Island’s only syringe exchange program since 2016.

Wolf said she believes Long Island should expand on low-threshold harm-reduction services. This means providing minimal demands, such as fentanyl test strips and naloxone, and offering rehab and counseling to drug users who desire it, instead of forcing it on them.

Wolf noted that more resources are needed, and she hopes the opioid settlement funds will provide an opportunity to address the issue of drug overdoses in new and creative ways.

“I would hate to see the opportunity that this money represents get pilfered away in more of the same,” Wolf said. “Clearly, we need help. We’re losing lots of people, and we need to do significantly more than what we are doing right now.”

Harm-reduction programs prevent hepatitis-C and overdoses, said Marilyn Reyes, a board member at Brooklyn-based Vocal-NY, a grassroots organization that advocates for universal access to harm-reduction services.

Reyes’s organization is a New York State Licensed Syringe Exchange Program, which means it offers sterile injecting equipment to drug users for safer injections. The program also offers to dispose of used syringes, ensuring that users do not inject themselves with contaminated needles. Vocal-NY also provides care connection services, such as referrals to drug treatment centers, housing assistance, and medical and mental health services.

The group “treats the whole person,” Reyes said.

Harm reduction is a welcome alternative for people who face discrimination because of their drug use, the stigma of which could prevent users from receiving proper care.

“The minute they disclose that they use substances,” said Steven Hernandez, chief of staff St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction, a Bronx-based multi-service agency that offers syringe access and disposal, “the provider might instantly be looking to get them into treatment, or not even give them a level of care that they would for someone who is not using substances.”

According to Hernandez, it is important for people who use drugs to decide to seek treatment. “It’s a lot easier when someone comes to that conclusion themselves, as opposed to it being hoisted on them,” she said.

A report in 2017 by the Manhattan-based Fiscal Policy Institute concluded that the opioid crisis had cost Long Island roughly $8.2 billion in economic damage that year, which was roughly 4.5% of the Island’s gross domestic product. Additionally, Suffolk County’s opioid burden, which accounts for deaths, non-fatal outpatient visits, and hospital discharges involving opioid overdoses, abuse and dependence, ranks as one of the highest in New York, according to the 2021 New York State Opioid Annual Report.

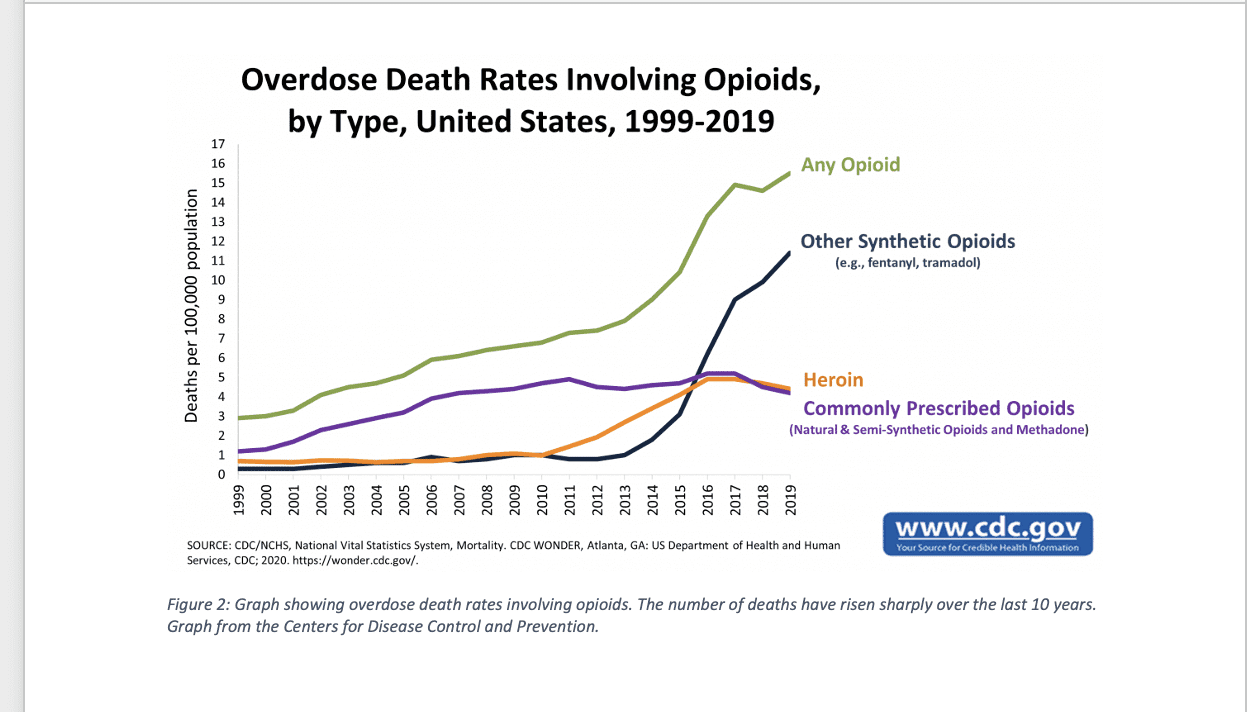

Drug overdoses do not discriminate, and can affect anyone.