By Robert Traverso

Editor’s note: This story first appeared in PULSE, which is published by the Lawrence Herbert School of Communication’s Magazine Production class for Hofstra University students and residents of surrounding communities.

The pandemic changed everything he did on a day-to-day basis.

“No gyms, no places of worship… You can’t go see friends or family… You can’t work on oneself or get a haircut or a shave… We were trying to help him find new things to do and healthy ways to cope, but everything we thought of was closed,” said Kathleen Alvino, a substance abuse counselor at Confide Counseling Center, a non-profit organization based in Rockville Centre, describing how Covid-19 has upended the life of one of her clients in recovery.

“The only thing he could find to do was go to the grocery store… Well, the grocery stores sell alcohol, too, and that led him to relapse,” Alvino said. “He was forced to be alone at a time when he needed to be with others the most. There was basically nothing to do but be alone.”

The isolation and social-distancing measures put in place to stem the spread of the coronavirus have had a profound effect on Long Islanders who struggle with substance abuse disorders, experts say. The isolation has led to a resurgence in overdoses and substance abuse to cope with mental health issues and economic angst amid the pandemic.

A July 2020 study found that 75,000 nationwide “deaths of despair” — caused by drug misuse, alcohol and suicide — can be attributed to the high levels of stress, isolation and unemployment brought by the coronavirus pandemic.

“The pandemic made it easier for individuals to get alcohol and drugs and made it harder to access treatment,” Alvino said. Overdoses on Long Island rose from 2020 to 2021, and alcohol sales have risen across the country since the pandemic began.

By 2019, the worst of Long Island’s opioid epidemic, dating back more than a decade, appeared to be waning. Opioid-related deaths had started to fall in 2017, a trend that was expected to continue.

Adrienne LoPresti, executive director at YES Community Counseling Center, a Nassau-based non-profit that works to prevent and treat substance abuse, said YES has experienced an uptick in requests for services. She also noted that the Nassau County Police Department alerted YES to a 55 percent increase in non-fatal overdoses in January compared to the same month a year before.

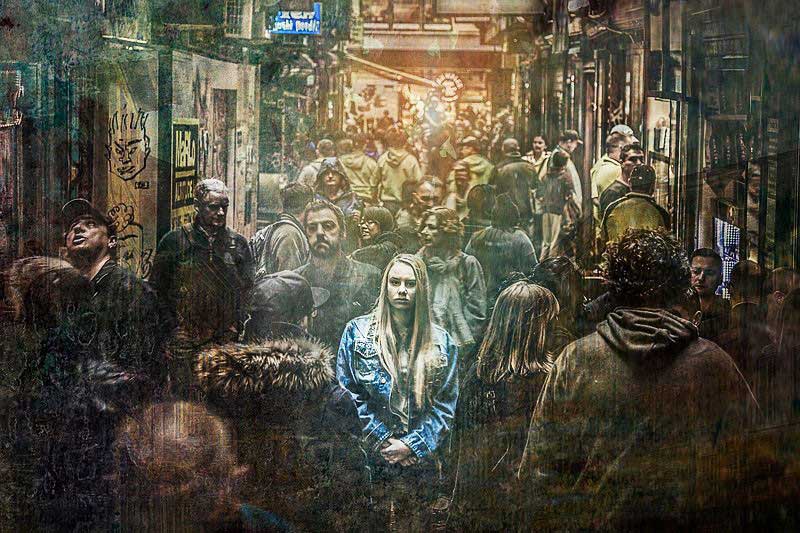

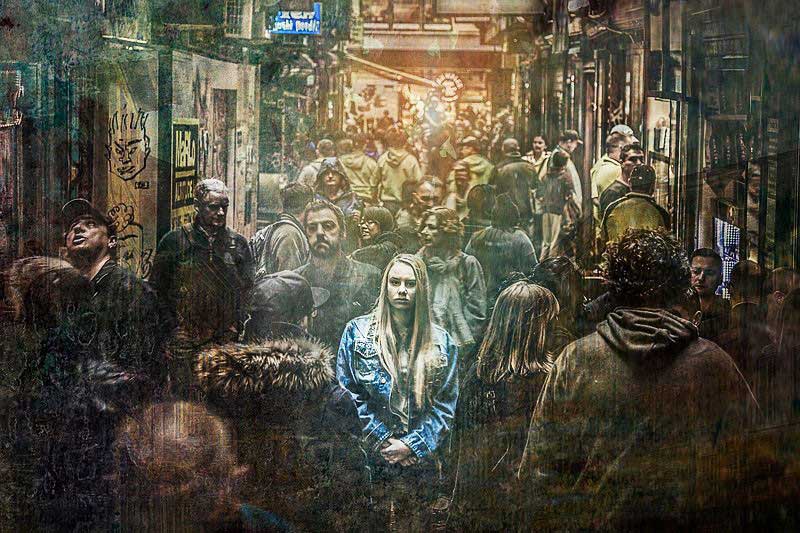

The impact of isolation

Local experts pointed to isolation as the number one factor that has led to the rise in overdoses. “People have been stuck home and some all alone… The isolation leads people to think about using, and for many, they have relapsed over the last year. Holidays spent alone because of restrictions on gathering… all of these things lead to depression,” Alvino said.

Tricia Ragusa, a certified peer recovery advocate at YES and a teacher, has been sober for five years, following a decade-long struggle with opioid addiction. She said a SUD often tempts individuals to isolate from society, which becomes their chance to abuse substances — this, she said, makes the mandated isolation from the pandemic problematic.

Ragusa said many YES clients, lacking pre-Covid stress-relieving outlets and activities, tell her it is hard not to abuse substances at home.

“All the ways we would encourage them to cope are not allowed… The outlets that people normally have don’t exist,” said Cindy Wolff, executive director at Tempo Group, a Nassau family-oriented addiction prevention organization. “For those who struggle with SUDs, “the impact of Covid is more profound… It’s just the reality of dealing with what is, for all intents and purposes, a mental health disorder during a time when what we’re being told to do is isolate and distance,” Wolff said.

Epidemics lead to increased stress because of loneliness and other factors; this often leads to depression, anxiety and low self-esteem. In fact, more than one in every four adults with a serious mental health condition also has a substance abuse disorder.

Individuals who struggle with substance abuse disorder are hypersensitive to stress, often leading to relapse or the use of substances to cope. “People are just very fearful, and drugs and alcohol are a way to numb that,” Ragusa said.

“The pandemic has increased a sense, for many, of fear,” LoPresti said. “For those perhaps already at risk for depression and anxiety, all the factors around the pandemic have compounded that… The desperation of community members, the intensity of needs, the level of distress has increased.”“He was forced to be alone at a time when he needed to be with others the most. There was basically nothing to do but be alone” — Kathleen Alvino

“Emotional health is intrinsic to the physical health of our people and community,” she said.

“When you’re in recovery, just being able to have control over your day is one of the foundations to how people stay sober… For many, they got to a place where things in life are good and they have managed to learn how to stay sober in the world. Then this pandemic came and took all that away, leaving people scared and alone and with limited resources for help,” Alvino said.

The lack of group meetings, due to social distancing requirements amid COVID-19, has made it harder to treat SUDs. // Photo courtesy of Baker131313/Wikimedia Commons

“More people are suffering from depression and anxiety than before due to this pandemic,” she added.

Lost connections

For many, the key to recovery from both SUDs and opioid addiction is group meetings and in-person interaction with others, but the pandemic has put a pause on so much of this. “There’s just so much relapsing happening because of the isolation,” Ragusa said.

One reason why, she said, is the end of in-person group meetings. “People don’t feel as connected on Zoom.” Isolated at home, many people are unable to interact with organizations that could provide help.

“When people are isolated in their homes, they can’t reach out for help… they don’t have a safety net outside of their home to identify that they need help,” LoPresti said.

This has led to desperation and loss. “I’ve never lost this many friends before recovery… So many people are dying,” Ragusa said, adding, “especially earlier in the pandemic when there was no access to in-person meetings.”

Group meetings are an integral part of the recovery process. “One of the most long-standing traditions in SUD treatment is self-help meetings… and a big part of that is the group experience, the power of the group… and during Covid, it’s a very different environment,” Wolff said, noting that isolation is the number one issue for people with SUDs during the pandemic.

“Even with telehealth services, which saves lives, for people who were already struggling, it’s not the best substitute for in-person services,” Wolff said.

Meetings over Zoom have not met this fundamental human need. “People need human interaction… Not having these things [has] a negative impact on everyone,” Alvino said. “Most of us have been in a situation where we were down, and someone smiling at you just makes you feel better for a moment. These little things that help are now gone, and that makes it harder to get out of that negative space,” Alvino said.

“The antidote to addiction really is connection,” Ragusa said. “When we get outside of ourselves and really connect with and help others, things really start to change.”

Addiction after Covid-19

“People who may not have recognized SUD as a problem in their life previously are now recognizing it,” Wolff said. “We were getting calls from people seeking services who were really more along in their illness than normally.”

Local experts fighting substance abuse on the ground predicted a challenging future for Long Islanders. “I think everyone’s mental health has taken a battering… and we’ll see an increase in self-harm, suicide, overdoses,” Wolff said.

Despite the dire situation, New York State and Nassau County instituted a 20 percent cut in substance-abuse resources during the first quarter of 2021, in addition to holds that were placed on resources in 2020. LoPresti called the move “shortsighted.”

New York and Nassau are yet to reveal if the cuts are temporary or permanent. She expects both the individuals affected and Long Island’s economy and society to feel the effects of this double crisis for a long time. “That’s what we’re very worried about — the long-term ripple effect of this pandemic,” LoPresti said.

Mental health concerns

Of more concern is the effect it will have on the life trajectory of those who struggle with SUDs and addiction in the long term. LoPresti worries that individuals coping with substances may not be able to return to a higher level of day-to-day functioning once society returns to normal.

“When the world opens back up and they’re told they have to go back out there into the world and negotiate the social pressures and the dynamics of the world they live in,” LoPresti said, “it’s likely they’re not going to have the tools and the skills to do that.”

“The more sober time you have under your belt,” Ragusa said, “the more sober references you have, the more tools you have in your toolbox, the easier it is to maintain long term sobriety.”