By Dorothea Armijos

Hofstra University’s Guthart Cultural Center Theater was filled Nov. 28 with a sense of community, with many audience members exchanging hugs, creating a warm and welcoming atmosphere. They had come to view the documentary film “Aftershock,” about the maternal mortality crisis in Black and brown communities across the United States. Many shed tears during the film, but someone was always there with a spare napkin and comforting presence.

The Cultural Center collaborated with the Women’s Diversity Network to present an emotional viewing of and panel discussion on “Aftershock.”

Premiering this year, “Aftershock” follows the families of Shamony Gibson and Amber Rose Isaac. In October 2019, Gibson, 30, died 13 days after giving birth. In April 2020, Isaac, 26, died after an emergency C-section.

Two weeks after Amber’s death, Shamony’s partner, Omari Maynard, reached out to Amber’s partner, Bruce McIntyre. Together, the two formed a bond amid their shared grief and began to fight with their families and communities for justice for their partners.

“We’re supposed to be the most advanced country in the world, but the racial disparities are becoming more and more evident each day,” McIntyre said in the film.

The film documents the long journey of Maynard, McIntyre and Shawnee Benton Gibson, Shamony’s mother. “Aftershock” shows the two families becoming strong social-justice activists fighting for equal maternal health care and legal protections for Black and brown women. The film emphasizes medical accountability, community and the power of art. The documentary introduces audiences to a multitude of people and follows the work of midwives and physicians fighting for institutional reform.

“Midwives existed in all nations and cultures of the earth. Midwives knew the feminine secret. Midwives were abortion practitioners since the beginning of time, helping women control fertility and control the use of their wombs,” said Helena Grant, NM, director of midwifery at Woodhull Medical Center in Brooklyn. “That’s a lot of power. In spaces where women have power, some men have a problem with it.”

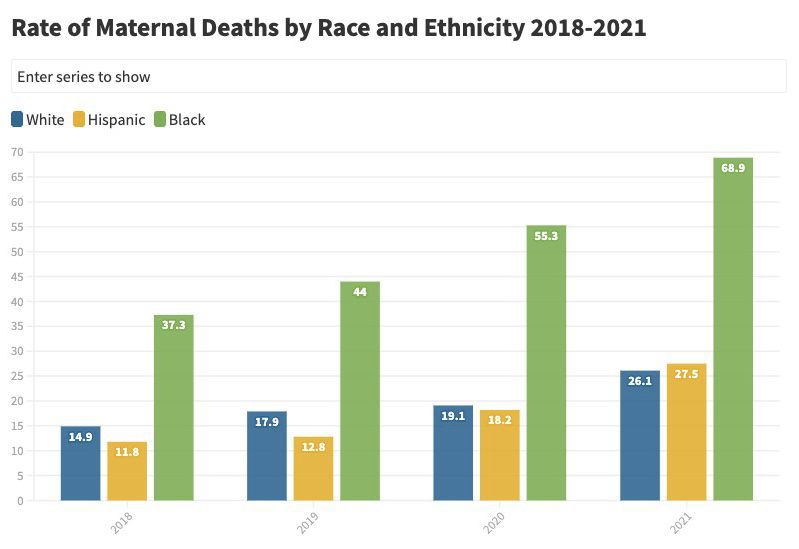

2018 was the first time the government started to track maternal mortality rates more systematically. In the film, Dr. Neel Shah, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Harvard School of Medicine, saw trends in the explosion of C-Section rates, noting that the procedure is performed 500% more than in the 1970s.

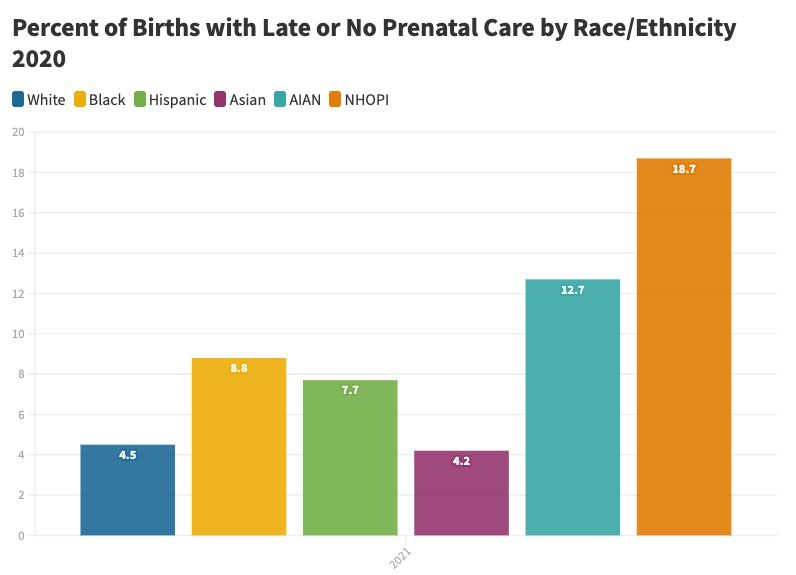

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that Black women are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than White women. “Aftershock” and the CDC both attribute the disparity to structural racism, implicit bias and variation in quality healthcare, preventing many women from racial and ethnic minority groups from receiving equal opportunities in economic, physical, and emotional health.

The panel featured two subjects of the film, Omari Maynard and Benton Gibson, along with doula Stephanie Henriques and midwife Dr. Heather Hines. Hofstra University Professor Dr. Martine Hackett, the Population Health Department chair and co-founder of the organization Birth Justice Warriors, moderated.

During the discussion, Maynard shared the responses he received after the film debuted. The documentary provides people with a voice and makes the community feel heard, he noted.

“It provides people with the understanding that just because you go into a hospital, and they tell you, doesn’t necessarily mean it’s gold,” Maynard said.

In the film, Neel said that in a hospital, the cost of doing a C-section is lower than the cost of a natural birth, and the shorter the labor is, the less it will cost. The hospital receives 50% more in insurance payments if a patient has a C-section.

Maynard shared the beauty of art he was able to find in his grief after his loss. He painted before Shamony’s death, but art became a cathartic space for him. Two months after Shamony died, Maynard said he painted seven or eight pieces of her. As his way of expression unfolded, he created a piece of Amber for McIntyre and other families who lost their partners in similar circumstances.

“Midwives existed in all nations and cultures of the earth. Midwives knew the feminine secret. Midwives were abortion practitioners since the beginning of time, helping women control fertility and control the use of their wombs.”

Helena Grant, Midwifery Director, Woodhull Medical Center

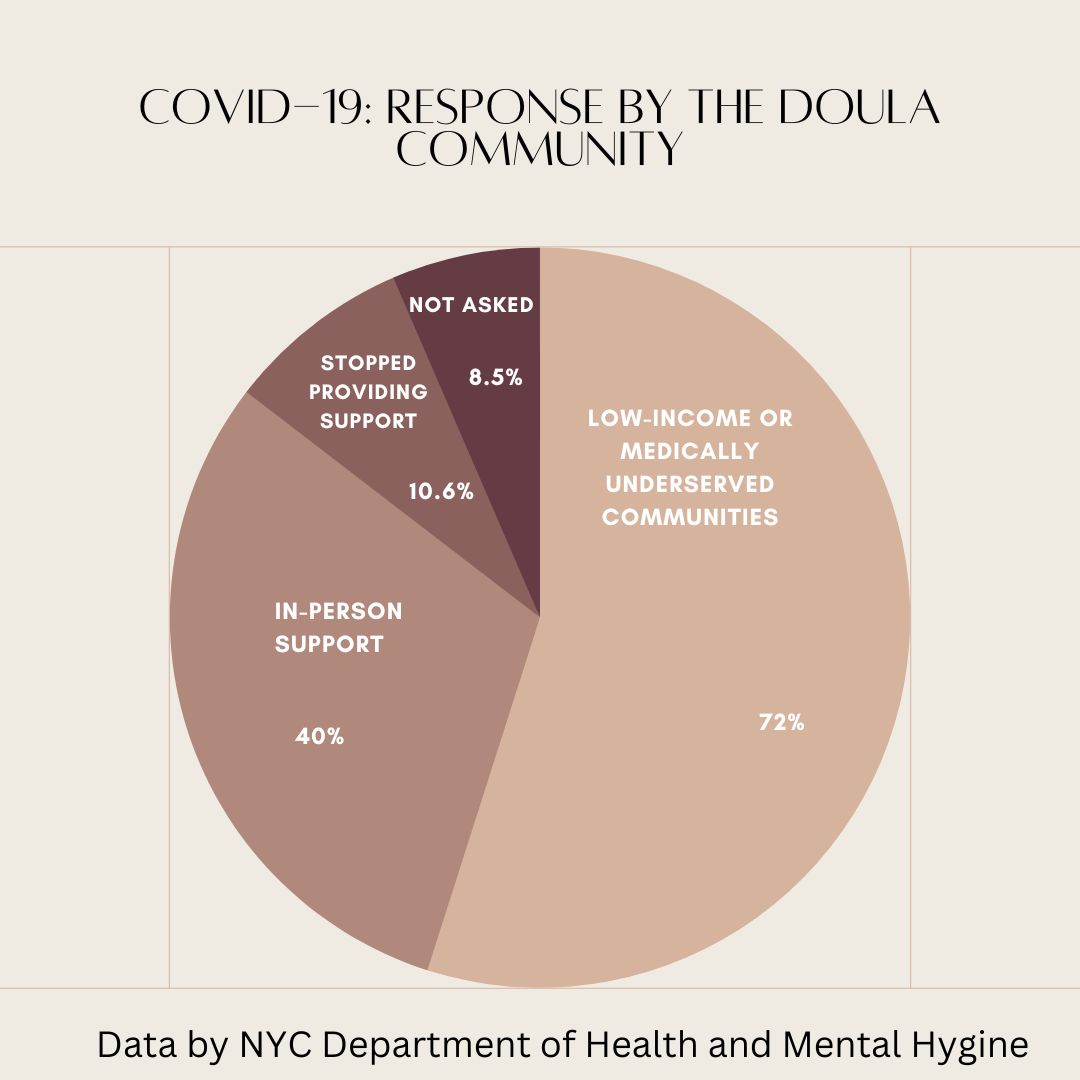

One of the last two subjects the panel touched on was the importance of midwifery and doulas.

Hines explained that midwifery comes from the Caribbean, but when she first arrived on Long Island, she found the majority of midwives were White, and only one hospital offered midwifery.

“As midwifery comes from the Caribbean and it’s cultured in the community, and here you are trying to establish community and don’t have mentors who look like you, it takes community out of the community,” Hines said.

Hines explained that nursing became the “end road” for those who wanted to become midwives. People went to school and received an advanced education to be able to serve their communities. But Hines said that most people who return back to school for higher education do not necessarily “have the funds, don’t have the support system,” and people of color often are not supported in higher education.

Henriques is a community doula in Brooklyn and on Long Island who helps clients be seen. Doulas have extensive training on how to access care that many expectant mothers may not. “When we walk into hospitals, there’s automatically going to be a power dynamic that’s going to exist,” Henriques said.

Doulas are birthing advocates. They use their knowledge to leverage and serve their clients. While doulas make sure their clients are “seen, heard and loved,” they also make space for them, repeat information, allow clients processing time, help them think through informed decisions and provide them with emotional support.

“Doulas have the time that sometimes doctors don’t have to spend with their clients, and they spend the time being able to fill in those gaps,” Henriques said.