By Michael Malaszczyk

Editor’s note: Part two in a two-part series.

It’s called Strong Island for a reason.

The toughness and tenacity of Long Island fighters is something Joe DeGuardia picked up on during Star Boxing’s earlier days in the 1990s, when most cards played in New York City or in Westchester County.

The Pioneers of Long Island Boxing

One can’t avoid discussing Gerry Cooney, Buddy McGirt, Jake Rodriguez and a few others when talking about Long Island fighters, according to Joe Higgins.

“Look at Bobby Cassidy,” Higgins said. “Man, look at Larry Stanton and Gerry Cooney, Buddy McGirt. All guys that I know, all friends that I watched come up from their very early days. Jake ‘The Snake’ Rodriguez and Willy Wise, they either became world champ or became very successful and maybe didn’t get the same credit that they should have because of where they were from.”

While the fighters noted by Higgins carried their heritage into the ring with them, it was the contenders and journeymen who fought on early Star Boxing cards that put Long Island on the map.

“We always had Long Island fighters [on our cards],” DeGuardia said. “Long Island had a pretty good boxing scene, I used to see, when I was training for the Golden Gloves years ago, when I was in law school on Long Island at Hofstra. I used to go to the gym, I thought they were good, they had some good fighters out there. I wouldn’t necessarily say that they have a certain style. But they are all tough. They will condition, they train, they work. We know Chris [Algieri] was always in great shape. Great conditioning, Joe Smith, great shape, great conditioning. Jamel [Herring], same thing.”

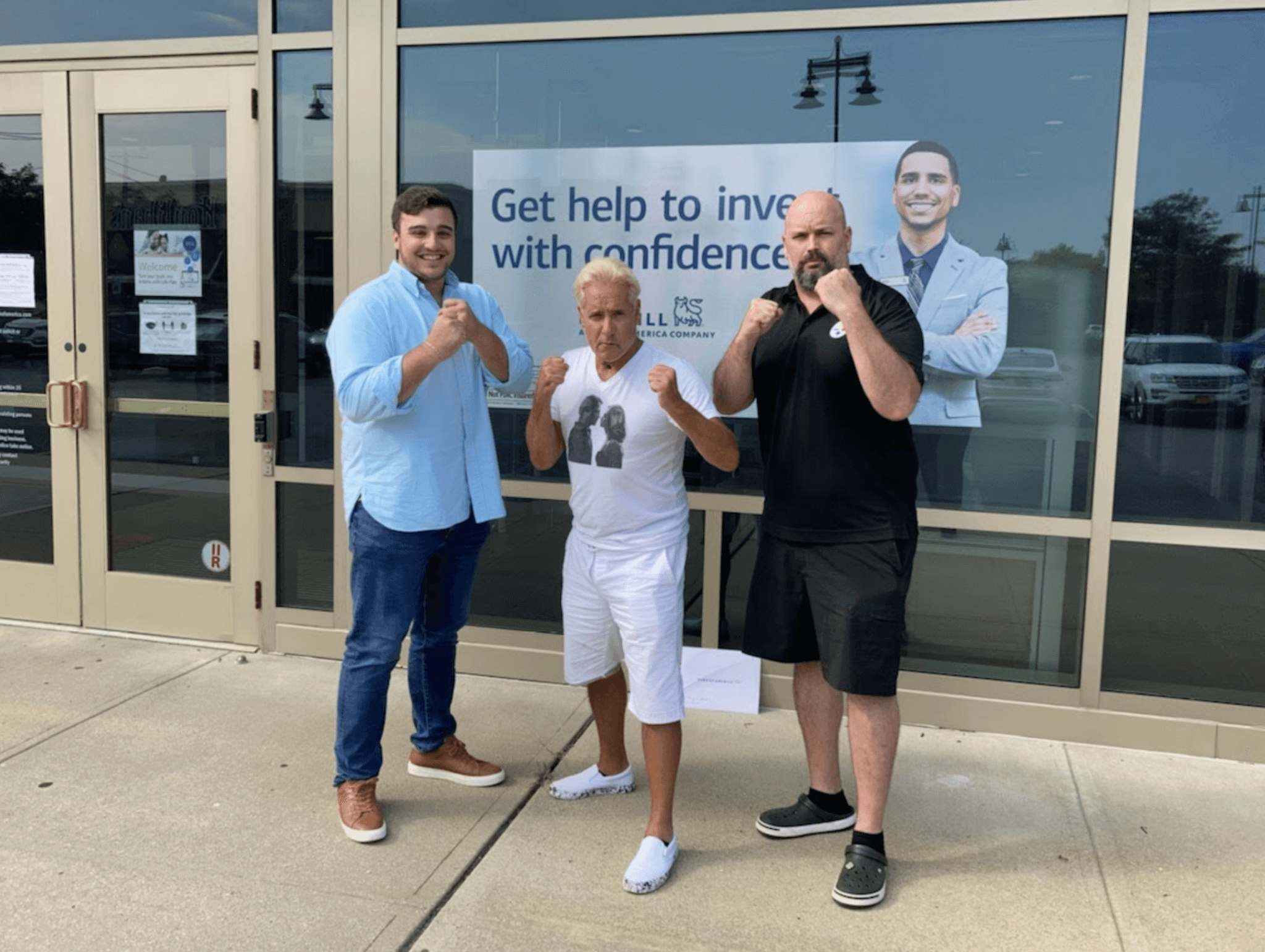

One particular fighter stood out: Michael Corleone, now 53, of Bellmore, who competed professionally from 1994 to 2005. Corleone shared the ring with several greats, including former welterweight world champion Yuri Foreman and former middleweight world champion Mikkel Kessler. Corleone was a fan favorite on Star’s cards.

“He had a great thing when he used to come in to the music of ‘The Godfather,’” DeGuardia said. “The fans would go crazy. It made us start keeping our ears to the ground for Long Island fighters.”

While Corleone himself, and many other earlier Long Island Star fighters, never fought at a sustained elite level, their ability to fill seats kept Star in the local market, which eventually led them to Algieri. The rest is history.

Corleone, like Higgins, was born in Brooklyn and moved to Bellmore. He joined the Navy after graduating high school, and after he got out, worked for his father’s garment business in Puerto Rico. It was there where he took up boxing at age 21, fighting several amateur bouts before being offered to fight back in the States, and eventually signed with Star Boxing.

“I was going for a run near a boxing competition, and some guys came out and asked me if I wanted to fight,” Corleone said of his Puerto Rico debut. “They had an amateur guy who needed to fight. I had never boxed before. They even said, ‘Don’t feel bad when you get knocked out.’ I said, ‘Ain’t nobody knocking me out.’ The guy gave me a bloody nose, so I clubbed him and won by knockout.”

Corleone founded Kayo Boxing, a West Hempstead gym, in 2004.

What Makes “Long Island Style?”

Asked what drove his own toughness, Corleone has a unique take. For a place that, according to Newsday, has a higher median income than the national average, it may be different than other places, he said.

“It has to come from within,” Corleone said. “I didn’t grow up poor, I grew up in an upper middle-class family. There was always food on our plates. We always had whatever we needed. So for me, I didn’t need to struggle so much. My struggle came from my desire to be great.”

It’s not a universal sentiment. Joe Higgins founded the Freeport PAL Gym because, he said, Freeport had issues with gangs and crime.

“I knew what a boxing gym can do for that situation,” Higgins said. “I know what boxing did for me.”

But Corleone and Higgins agree on another factor that drives Long Island’s toughness.

“We take fighters, we take the everyday person,” Corleone said. “We take people looking to lose weight, people who maybe aren’t so socially involved. We take them in, and we create our own family.”

The sense of community all over Long Island is strong, according to both.

“When you have a really good functioning boxing gym, it’s all about the community,” Higgins said. “That’s always been my drive, but for the other athletes, some of them just want to get in shape and feel good about themselves, and others want to get the highest levels they can in the sport. Some of them just want to compete in a fight to say they did it, you know, but everyone works equally hard.”

The toughness of the fighters, according to Alex Vargas, is also driven by the relationship between Long Island and New York City.

“We have that chip on our shoulder,” Vargas said. “We know that we’re going to fight these guys from the city with the political strength behind them, and the big names behind them and the hype around them, when we come in to fight them. We have to have that toughness to be able to get our name out there and beat these guys.”

It’s something Higgins agrees with.

“Don’t call me the stepchild of New York City,” Higgins said. “Don’t think we’re a bunch of punks out here.”

The Future For Long Island Boxing

The local boxing scene has grown. Rockin’ Fights cards continue to show at the Paramount and other venues. Higgins, Corleone and others continue to help shape the next generation of Long Island boxers.

But the sport has a long way to go. While Star Boxing has earned recognition for its work on Long Island, its monopoly means that fighters from the region must sign with them to have a home field advantage – and if they cannot, they are out of luck. And amateur boxers don’t have the varsity system backing them up like other sports do.

That’s why Long Island Boxing Charities was founded in 2018 by Rich “Boxer” Tintella. It was taken over by longtime fans and Long Islanders Matthew Pomara and Tony Palmieri. It aims to provide a bottom line for Long Island boxers, whether that’s donating gear to gyms or paying for a fighter’s hotel costs when fighting out of state.

“It’s come a long way, but if I were to give Long Island boxing a grade, I’d give it a C,” Pomara said. “There’s really only one promoter who’s active on Long Island, and that is Star Boxing. Star Boxing does a great job, but the fighters need options.”

LIBC’s long-term goal is simple: to no longer need to exist.

“I’m very proud of what we’ve done here, I’m very proud of LI Boxing Charities, and I’m proud to have my name associated with it,” Pomara added. “But it’s like shooting a pea at a tank. The problem is such a bigger problem. But I think the problem is fixable. I really feel like we can fix this problem, because what we need to do is we need to help the fighters get health care after their careers are over. We have to help them with health care after their career. You know, some people need counseling. And then some people also need some financial assistance.”

With that lack of a unified system for athletes like in other sports, education is another goal of LIBC. Tony Palmieri worked at Star Boxing from 2017 to 2024, and saw firsthand the kind of education fighters need.

“Knowledge is power, and I think that the first step is having a place, and this is something Matt and I have discussed, creating basically like a curriculum almost for fighters,” Palmieri said. “What does a contract look like? What makes a good manager, what makes a good promoter? These are all areas in which I think many fighters don’t ever discuss. And then all of a sudden, they’re in the whim of a negotiation or trying to sign somewhere or, or take a fight. And these are things that become overwhelming.”