By Madeline Armstrong

Book censorship has been a growing concern among freedom of expression advocates in recent years, including on Long Island, which has a long history of school districts banning books.

Classics such as “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee and “Of Mice and Men” by John Steinbeck have appeared on the American Library Association’s Most Challenged Books list as recently as 2020, meaning school and library officials around the country are pulling them off their shelves.

“We’re seeing a three- to four-time increase of what we would normally see in a given school year, so this is a crisis,” said Nora Pelizzari, director of communications for the National Coalition Against Censorship, speaking on banned books.

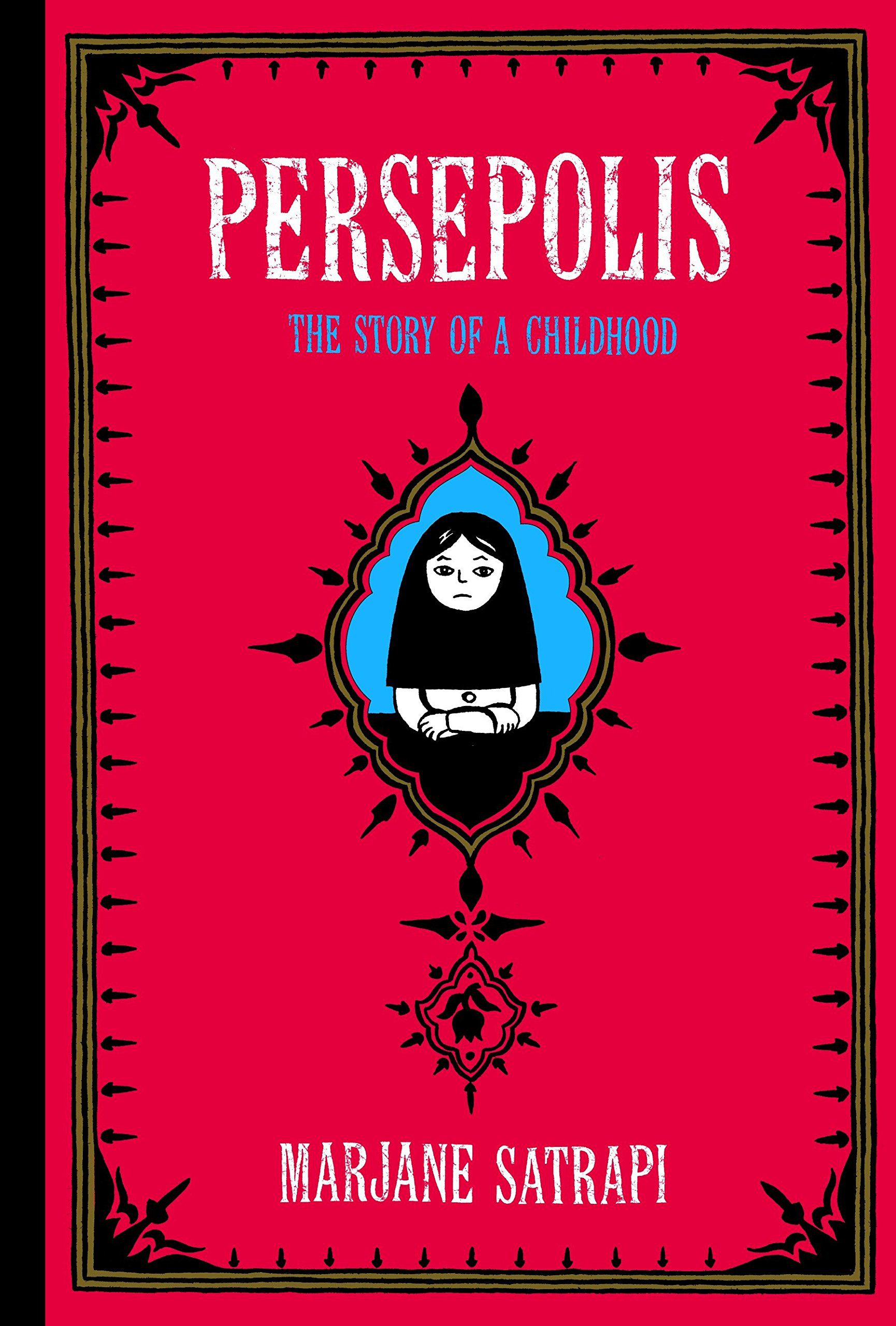

In June 2021, “Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood,” an award-winning comic-style book by Marjane Satrapi about an Iranian girl during the Islamic Revolution of 1978-79, was removed from the 11th-grade reading list by the Commack School District after officials there said it was not age-appropriate.

“You had people of South Asian background who said, ‘This is the only book we get to read where we appear,’” said Dr. Alan Singer, a professor of teaching, learning and technology at Hofstra University and an occasional Long Island Advocate op-ed writer.

Commack parents had reportedly complained about the teaching of Critical Race Theory, which examines racism within societal systems and history. School officials said the theory is not taught in Commack, according to Newsday.

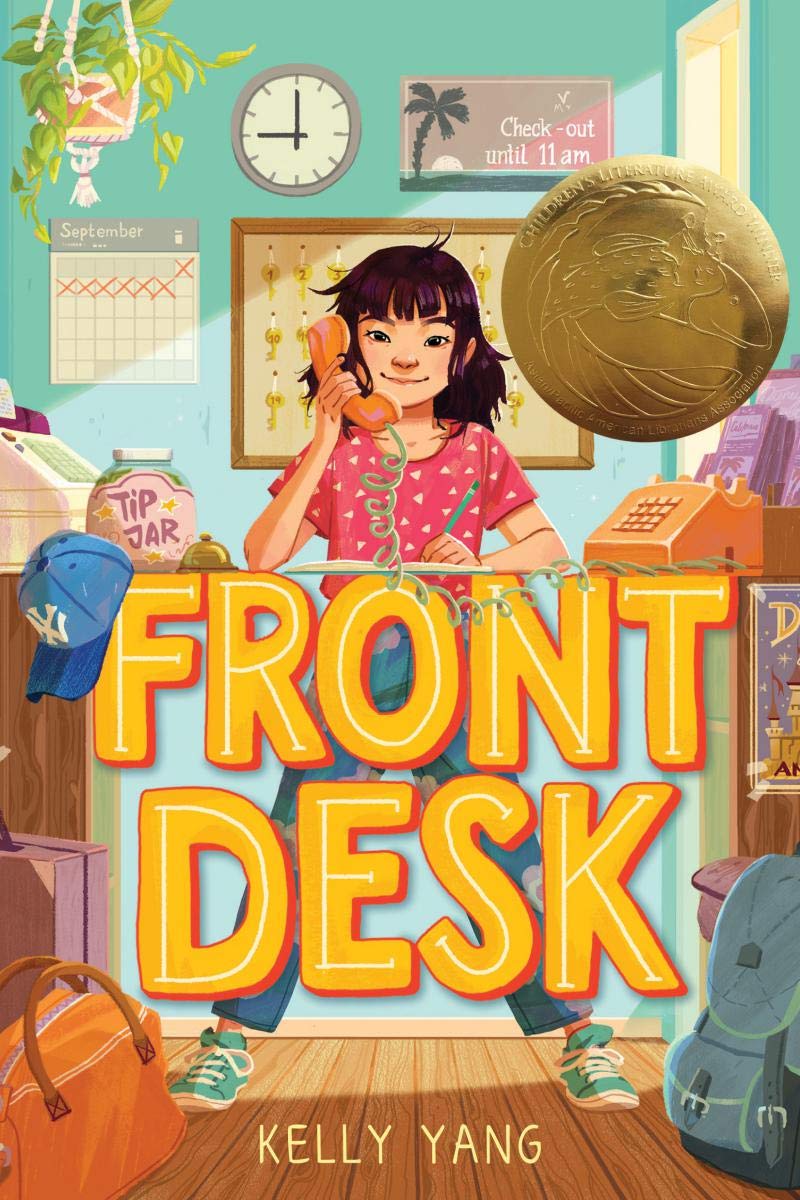

Last October, “Front Desk,” a middle-grade novel by Kelly Yang, was temporarily banned in the Plainedge School District after parents complained the book was “racially diverse.” In a letter to the school district, one parent said books that are taught in the schools should not address CRT or the Black Lives Matter movement. Some had complained that in “Front Desk,” a white officer’s false accusation of theft against a Black motel guest made law enforcement look bad. The book was later reinstated, but parents were given the chance to opt their children out of reading it.

“Front Desk” is largely about the Chinese immigrant experience in the 1990s.

Banning such a book “sends this message that certain topics and certain ideas can’t even be discussed,” Pelizzari said. “If you can’t have a book in the library about it, how can you have a conversation about it.”

Dr. Amy Catalono, a professor of teaching, learning and technology at Hofstra, said children of different backgrounds “need to see themselves represented in books, and they also need to be exposed to people and situations not familiar to them in order to learn to accept diversity.

“Censorship comes about when a group of people decide to inhibit all people from information,” Catalano continued. “If a parent feels strongly about their child not having access to the book, they can deny access to their child, but they don’t have the right to deny access to other children.”

The history of Long Island districts banning books dates back decades. In 1975, the Island Trees Board of Education received a complaint from a community group about nine books that they said were “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic and just plain filthy.” The district then removed them from the schools. A group of students, however, challenged the decision, and the case went before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1982. The court ruled in favor of the students’ First Amendment rights, and the case became a landmark decision.

“Even books with the most hateful concepts and ideas need to be examined,” said Jackie Farmer, senior program officer of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, a nonprofit that defends and educates students on their First Amendment rights. “There’s a reason why in political science classes you end up reading ‘Mein Kampf’ and excerpts from books like that. It’s because they played a major historical role.”

“Mein Kampf” is the 1925 autobiographical manifesto of Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler.

Pelizzari argues that removing books from schools and libraries is counterintuitive and is a disservice to students. “The whole point of education is to be challenged, to encounter new things,” she said.

“It’s the job of the school to teach the culture of the community, and the books we offer should reflect that,” Catalono said. “That includes books about gay and trans families, families who may have a parent in prison, and families of diverse backgrounds and colors and religions.”

Dr. Andrea Libresco, a professor of social studies education and civic engagement at Hofstra and a board member of the Nassau County chapter of the New York Civil Liberties Union, said most book censorship goes unnoticed or unreported. “Only a fraction of the censored [books] are ones we find out about,” she noted.

“Books are disappearing very quietly and quickly in a lot of places,” Pelizzari said. “A lot of times censorship succeeds when it happens in silence.”

Singer said he believes decisions about which books to include in libraries and school curricula should be left to education professionals instead of parents. “We have to stand up for the freedom for kids to learn,” he said.

NCAC has been around for 50 years and has many resources for people who are dealing with book censorship in their schools and communities, including the Kids Right to Read Project and the Book Banning Hotline. Through the hotline, people can report censorship, and then NCAC will start an investigation and provide freedom of expression advocates with resources.

“We work with school districts to try to improve and strengthen their policies around book selection, book review, material review and also work with them to navigate book challenges when they arise to make sure that they’re protecting students’ expression and right to information,” said Pelizzari, whose group is a coalition of more than 50 nonprofits.

Pelizzari said she believes the recent increase in censorship is a “politically motivated attack on students’ ability to access information,” and she said there is a trend in the types of books that are being challenged, including books about racism, sexuality and LGBTQ.

“Most of the books being challenged or banned tell stories of people who have traditionally been underrepresented on library shelves,” she said. “There are a lot of students out there who have had a harder time finding books that tell their stories or that tell stories that they can relate to and that they connect with.”