By Madeline Armstrong

Editor’s note: The following is part three of a three-part investigative series by Madeline Armstrong, who recently completed her master’s in journalism at Hofstra University. The series was her capstone project, which passed with honors.

Long Island immigrant advocacy organizations almost unanimously agree that access to legal representation is the biggest barrier that undocumented immigrants face. In criminal court, everyone is entitled to a lawyer, and if they do not have one, the state will provide them with one.

However, since undocumented immigrants are not U.S. citizens, they are not entitled to legal representation. They must either pay out of pocket for a lawyer or represent themselves in immigration court.

“No one gets free counsel in immigration proceedings,” said Alexandra Rizio, managing attorney at Safe Passage Project, an organization that provides free legal services to unaccompanied minors. “In immigration court, the matters are really life and death. People have fled here because they fear for their lives. They still can’t get an attorney in immigration court if they can’t afford one.”

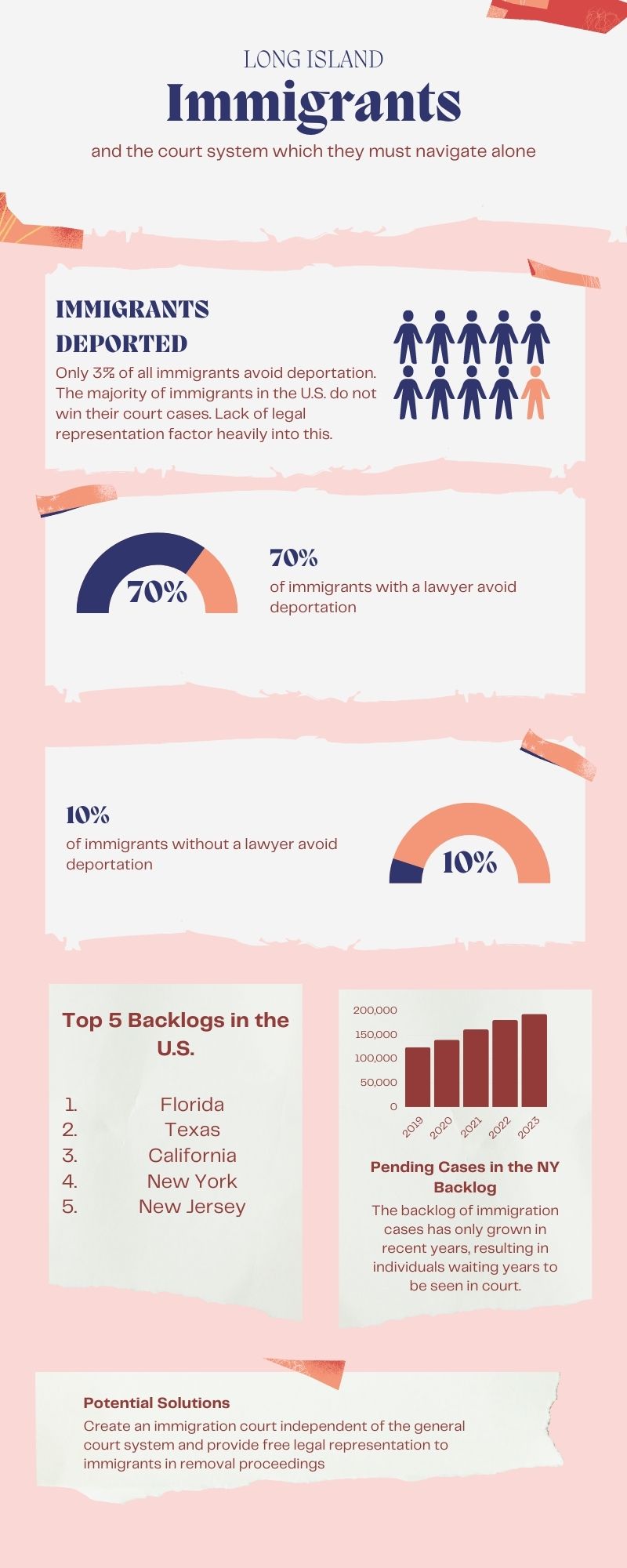

The U.S. court system is too complex for immigrants to represent themselves, according to experts. “There’s no one who is in a complicated court system who can represent themselves adequately,” said Patrick Young, director of organizing and strategy for the New York Immigration Coalition, an advocacy organization that represents over 200 immigrants rights groups in New York. People who have a lawyer typically win about 70% of the time, and if you’re unrepresented, you win maybe 10 or 15% of the time.”

Shayna Kessler, advocacy manager for Vera’s Advancing Universal Representation initiative, said the initiative advocates for expanding access to publicly defended deportation representation for undocumented immigrants.

“We really see it as a promising immigration policy to support people confronted with a really harsh and complex system,” Kessler said.

In the meantime, many organizations are providing pro bono services to undocumented immigrants needing representation. However, according to Rizio, there are not enough immigration lawyers to meet the need.

“We don’t have sufficient numbers of attorneys,” she said. “We don’t have sufficient numbers of interpreters, social workers, etc. because the federal government has decided that it is not a criminal case so there is no constitutional requirement that attorneys be provided, and I think that it is just morally wrong, and I think that it’s not serving anybody in the court system.”

“There’s no one who is in a complicated court system who can represent themselves adequately.”

Patrick Young, New York Immigration Coalition

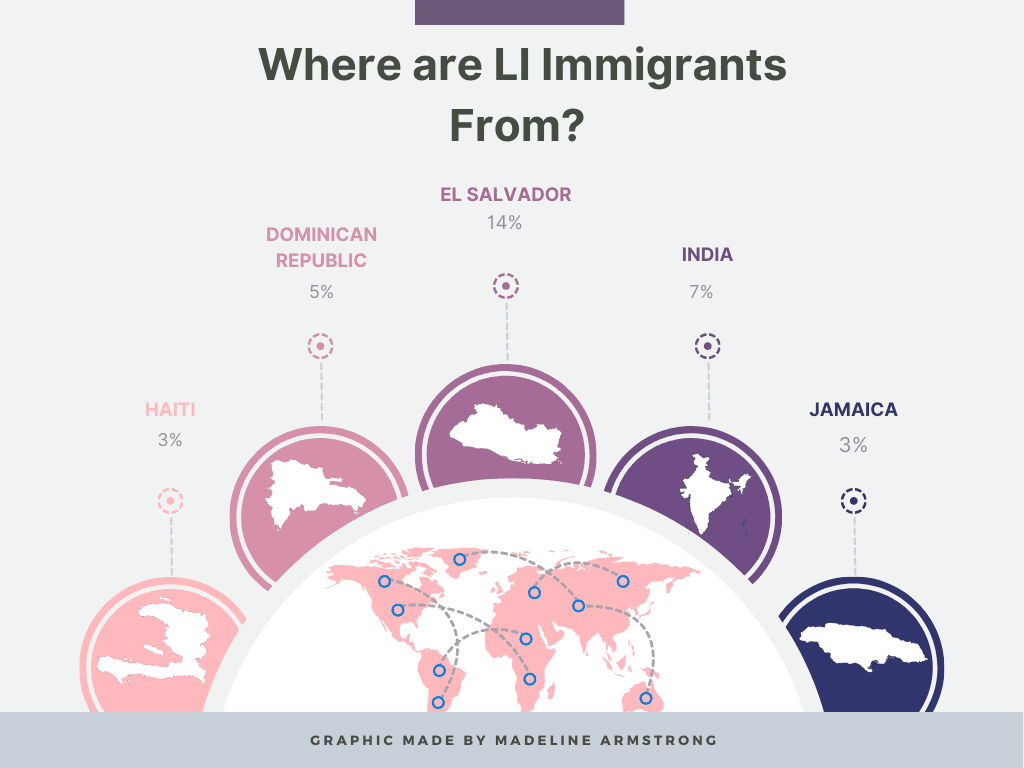

Elise De Castillo, executive director of the Hempstead-based CARECEN (Central American Refugee Center), which provides pro bono legal services to Long Island immigrants, said that in addition to free legal representation, an overhaul of the immigration court system is overdue. New York state has one of the largest case backlogs in the country.

“Currently, we are seeing heavily impacted dockets in the multiple New York immigration courts, with 189,798 cases in the backlog as of Dec. 31, 2022,” said Mimi Tsankov, president of the National Association of Immigration Judges. “This is the fourth-largest backlog in the country.”

This means immigrants are waiting years to be seen in court. This is due in part to the sheer number of immigrants arriving in New York but also the lack of immigration judges and interpreters, as well as clerical errors.

“Justice delayed is justice denied,” Tsankov said. “They are in a legal limbo, waiting to understand how the court views them, how the justice department and the executive branch views their status in the United States.”

The dysfunction of the immigration court system can be seen at 7 a.m. with immigrants lined up outside the building waiting to be seen.

“People are lining up outside the immigration court at three, four in the morning to try to go to their [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] check-ins,” Rizio said. “ICE overschedules people and then doesn’t let everyone go into the building. If you don’t go to your ICE check-in, that can result in ICE recommending that you be deported.”

Many immigrant advocates said an independent immigration court is a possible solution. “One of the enduring solutions that we proposed and that the last Congress looked at very closely through hearings and the introduction of a bill in the House of Representatives was the creation of an independent immigration court,” Tsankov said, “and we continue to think that is a very good solution for the backlogs and the ability for the respondents who are appearing to court to have better access to justice.”

Until these changes are made, immigrants will continue to wait years to defend themselves in a court system that they don’t understand, have to wait even longer due to clerical errors and lose their case because they did not have access to legal representation.

“Immigrants are essential to the fabric of our state,” Kessler said, “so investing in supporting their ability to navigate these really complex proceedings with a modicum of fairness and access to counsel of their side is really a bare minimum in a daunting and challenging system.”