By Madeline Armstrong

Editor’s note: The following is part one of a three-part investigative series by Madeline Armstrong, who recently completed her master’s in journalism at Hofstra University. The series was her capstone project, which passed with honors.

Martina, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico, has lived on Long Island for 23 years. She made the journey to the Island in 2000 with her ex-husband and two young daughters because she had friends who had already immigrated and said that there were many job opportunities here.

“Unfortunately, they never told me any of the inconveniences that were going to happen to me once I arrived,” Martina said.

The biggest challenges for Martina were not being fluent in English and affording the high living cost of living.

“Between us, we had to work like three jobs to afford basic necessities like food, paying for rent and bills,” Martina said.

During her first decade in the United States, Martina’s ex-husband was deported four times for driving while drunk. The last time he was deported, Martina considered returning to Mexico because life in America was so challenging, but her daughters begged her to stay. They had spent most of their lives on Long Island and didn’t want to leave their friends, school and home.

“I decided to stay,” Martina said. “I had to get four jobs to pay the rent.”

Three years later, Martina was diagnosed with Stage IV cancer and was told she had three weeks to live.

“The treatments were going to be super expensive because I didn’t have any documentation or health insurance,” she said. In addition to having to pay exorbitant amounts of money to receive life-saving treatment, Martina faced discrimination in the hospital.

“Some doctors didn’t want to touch me,” she said. “Throughout my time here, I have felt discriminated against. The [the United States] is my home now, so it’s something I have to get used to.”

Martina’s treatment was a success, though, and she was deemed cancer-free. Ten years later, however, she is still thousands of dollars in debt.

“The most important thing to me is medical coverage,” Martina said. Due to financial constraints, she has not had any medical appointments in three years and is fearful of the cancer returning.

Martina currently lives in Riverhead and works as a housekeeper for two summer homes in the Hamptons. She works long, hard hours in the summer to be able to afford her year-round expenses. Martina pays taxes and has been a contributing member of American society for 23 years. She considers the U.S. her home and wishes that she could be recognized as a U.S. citizen.

“I want there to be a solution for folks like me to be able to attain citizenship,” Martina said.

The immigrant experience

Martina’s story is not unique. She is one of over 500,000 immigrants living on Long Island.

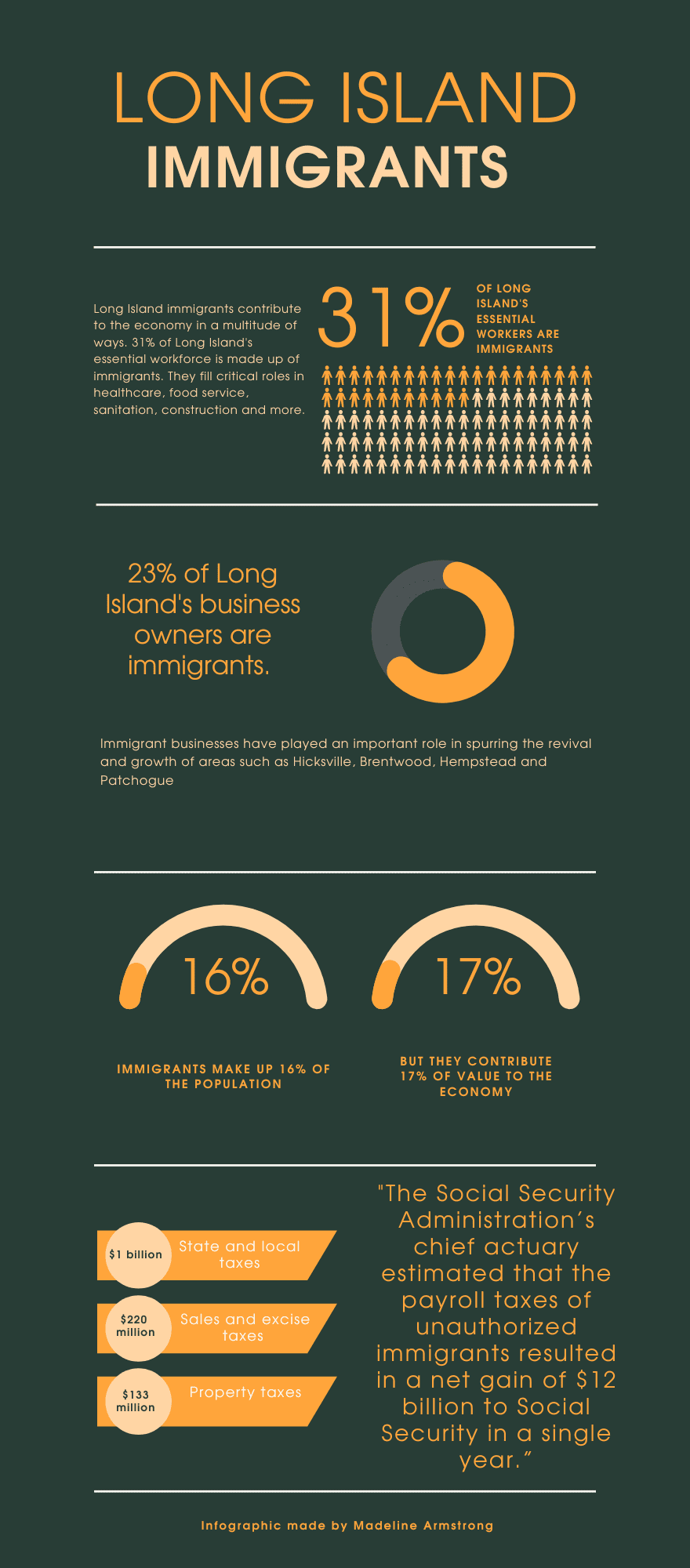

“The immigrants are almost a fifth of Long Island’s population, more than a fifth of its workforce, a fifth of its business owners,” said Patrick Young, director of organizing and strategy for the New York Immigration Coalition, an advocacy organization that represents over 200 immigrant rights groups in New York. “They are a vital part of Long Island, and it’s just very important that [they] not be neglected.”

Thirty-one percent of Long Island’s essential workforce are immigrants working in critical roles in construction, food service, healthcare, sanitation and more, according to an article titled Long Island’s Immigrants are Integral for its Economic Recovery written by Steve Bellone and published in the Long Island Press.

“If they were forced to leave, we could lose approximately $638 million in economic output and $373 million in annual spending,” reads the article.

Twenty-three percent of small businesses owners on Long Island are immigrants, according to a study published by the nonprofit, nonpartisan Fiscal Policy Institute.

“Immigrant businesses have played an important role in spurring the revival and growth of areas such as Hicksville, Brentwood, Hempstead and Patchogue,” reads the study.

Additionally, many undocumented immigrants pay New York taxes.

“The Social Security Administration estimates that roughly half of all unauthorized immigrants have payroll taxes withheld for Social Security and Medicare,” reads the study. “Because these taxes are paid using false Social Security numbers, among other reasons, unauthorized immigrants are highly unlikely ever to receive benefits.”

It is estimated that the taxes of unauthorized immigrants has resulted in a net gain of $12 billion to Social Security each year.

Although immigrants contribute economically and culturally to Long Island communities, they face a host of problems trying to survive on Long Island, including housing, language barriers and discrimination.

“Long Island has a tremendous affordable housing problem,” said Juana Torres, legal director at Sepa Mujer, a nonprofit organization that works to support immigrant women on Long Island. “For immigrants, you’re probably looking at either illegal housing or substandard housing.”

This means that immigrants are living multiple families in a house and in conditions that are unfit to live in.

“People are living in situations that are not good and they have no other places to go,” said Minerva Perez, executive director of OLA of Long Island, a Latino advocacy group in the East End of Long Island. “You could be living in a situation that you know isn’t great, but it’s the only situation that you have. These become scenarios that harm families, harm children.”

“Undocumented immigrants on Long Island almost invariably reside in the poorest areas with the worst housing conditions,” reads a report titled, Alternative Enumeration of Undocumented Salvadorans on Long Island by Sarah Mahler. “They occupy basements and overcrowded, often illegal, apartments because they are excluded from other areas and/or because they need to lower their housing costs. Due to their undocumented status, these individuals do not qualify for government-subsidized housing and other benefits to ease their burdens.”

Additionally, undocumented immigrants do not have access to homeless shelters on Long Island.

“You have a right to shelter if you live in New York City. It doesn’t matter your legal status. We do not have the same situation out here,” said Sister Janet Kinney, director of the Long Island Immigration Clinic, an organization that assists immigrants with their asylum cases. “Suffolk County Department of Social Services requires that they have a Social Security card.”

“The Social Security Administration estimates that roughly half of all unauthorized immigrants have payroll taxes withheld for Social Security and Medicare. Because these taxes are paid using false Social Security numbers, among other reasons, unauthorized immigrants are highly unlikely ever to receive benefits.”

Fiscal Policy Institute Study

Discrimination against immigrants has been proven to be rampant on Long Island.

“Latino immigrants in Suffolk County live in fear,” reads a report titled Climate of Fear: Latino immigrants in Suffolk County, N.Y.: A Special Report from the Southern Poverty Law Center, Montgomery, Alabama. “Low-level harassment is common. They are regularly taunted, spit upon and pelted with apples, full soda cans, beer bottles and other projectiles. Their houses and apartments are egged, spray-painted with racial epithets and riddled with bullets in drive-by shootings. Violence is a constant threat. Numerous immigrants reported being shot with BB or pellet guns, or hit in the eyes with pepper spray.”

Hope for immigrants

Many nonprofit immigrant advocacy organizations on Long Island are attempting to address the myriad of issues that Long Island immigrants suffer from.

“The limited reasons that we have in our region to serve immigrants are being spread even more thin than they have been in the past,” said Elise De Castillo, executive director of CARECEN (Central American Refugee Center), an organization based in Hempstead that provides pro bono legal services to Long Island immigrants. “In a region where we’re all functioning past capacity, there’s no way that we can meet all the needs of every person who comes to our door.”

While CARECEN’s focus is on providing legal support to Long Island immigrants facing deportation, they are having to broaden their approach to address the multifaceted needs of immigrants.

“We’re looking at the problem holistically, triaging needs to make sure we’re meeting the most urgent needs first,” Castillo said. “Oftentimes we think that access to an attorney is the number one need for immigrants facing deportation, but if you don’t have food on the table or a roof over your head, who is standing next to you in immigration court becomes much less important.”

Advocacy organizations agree that it will take a comprehensive approach to address all the needs of Long Island immigrants and ensure they have everything they need on their path to citizenship.

“The nonprofit sector really needs to work together to coordinate and make sure that the services that are needed are in existence in the places that are needed,” said Rebecca Sanin, president of the Health and Welfare Council of Long Island.

Martina pleads for a path to citizenship. Sitting with her legs crossed, hands shaking and tears streaming down her face, she talks about her love and dedication to the United States.

“I have faith that someday there will be some sort of immigration reform,” she said. “This is my home.”