By Scott Brinton

The soccer players, all 10- and 11-year-old members of the Panteras, or Panthers, started to assemble in a semi-straight line in front of the net before 5 p.m. for their 5:30 practice on a recent Thursday, firing furious shots on goal, conversing at breakneck pace in Spanish and occasionally screaming in delight when a ball, booted from afar, landed squarely at the back of the net.

It was a seemingly chaotic, yet perfectly organized scene on a back field at NuHealth’s A. Holly Patterson Extended Care Facility in Uniondale on this partly cloudy, 75-degree day.

All the while, parents and guardians pulled up in mini-vans and SUVs to drop off their kids. Some parked and sat cross-legged on the sidewalk at the edge of the unlined field full of clover, watching intently from beneath the shade of soaring oaks while chatting in Spanish on their cell phones.

Within an hour, all four soccer fields there were full of children, many first-generation immigrants from Latin America, laughing and huffing their way through their practices, all led by volunteer coaches.

This is where, week after week, the New York Soccer Latin Academy prepares for competition in the Long Island Junior Soccer League and any number of summer tournaments. The academy was founded in 2002 to give Hispanic boys and girls, ages 5 to 19, a safe place to learn the fundamentals of the game that, for decades, has captivated the peoples of Mexico and countries throughout Central and South America.

South of the U.S.-Mexican border, soccer, or fútbol, is more than a game; it is deeply ingrained in the culture of Latin America, said Francisco Guerrero, a NSYLA coach who founded the club and owner of the Sanzivar Auto Repair and Body Shop in Hempstead.

“We want to give our kids the best we can give them,” Guerrero, 54, said during an interview at his dimly lit office, whose walls are covered by NYSLA team photos. “Everybody who wants to learn, we’re going to give our time to teach them soccer.”

Registration is $400 for the year, divided in two payments, to cover the cost of LIJSL registration and uniforms. For players in need, their families pay what they can. No child is cut. In these respects, NYSLA is very different than many Long Island youth soccer clubs, where travel fees and expenses can run into the thousands per year, many trainers are paid, and players, particularly in the older divisions, can be cut.

Finding a footing in America

In Guerrero, players are learning from one of the best high school soccer players in Nassau County history. Guerrero, who took up soccer at age 6 or 7, emigrated from San Miguel, El Salvador to Hempstead in 1980, when he was 12 — in large part to escape the Salvadoran Civil War that had erupted only a year earlier and raged through 1992, with an estimated 75,000 civilians killed at the hands of government forces, according to the Center for Justice and Accountability. Children as young as 11 and 12 were kidnapped and forced to fight for the government or the guerrillas.

Soccer consumed Guerrero as a young man. In El Salvador, he said, the game “is everywhere — the mountains, the small [towns]. Everywhere, the kids want to play soccer.”

At Hempstead High School, Guerrero was named an All-American and racked up a cabinet full of other soccer honors, including the the Jim Steen Award in the fall of 1984 as Nassau’s top soccer player during his senior year. The county’s high school coaches vote on the winner. A photo of Guerrero in action on the field graced Newsday’s Sports Section when the award was announced.

Guerrero went on to play for two seasons for upstate Ulster County Community College, where he was also named an All-American, and for Club Deportivo Águila, a top-tier Salvadoran professional team in San Miguel, for three years.

Guerrero then joined the U.S. Navy, playing soccer in the military as well. He was sent to the Persian Gulf during Operation Desert Storm in early 1991 and served in the Navy for five years total before returning home to Hempstead and becoming a mechanic with the help of his family. A blue Iraq War veteran baseball cap sits atop a filing cabinet behind his desk at his shop.

Guerrero said he believes every child should be afforded the chance to play, regardless of ability, noting, “I saw that some kids were overweight but wanted to play . . . A kid is a kid. If they like it, they will learn, and they will put the effort.”

Over the past two decades, he estimated, some 7,000 young people have gone through the NYSLA program, most from Uniondale and Hempstead, though any child is welcome. NYSLA, Guerrero said, is his way of giving back to the community that has supported him for the past 42 years. “I had people who helped me when I came here,” he said. “I’m here because of soccer.”

A kid is a kid. If they like it, they will learn, and they will put the effort.”

Francisco Guerrero, NYSLA founder and coach

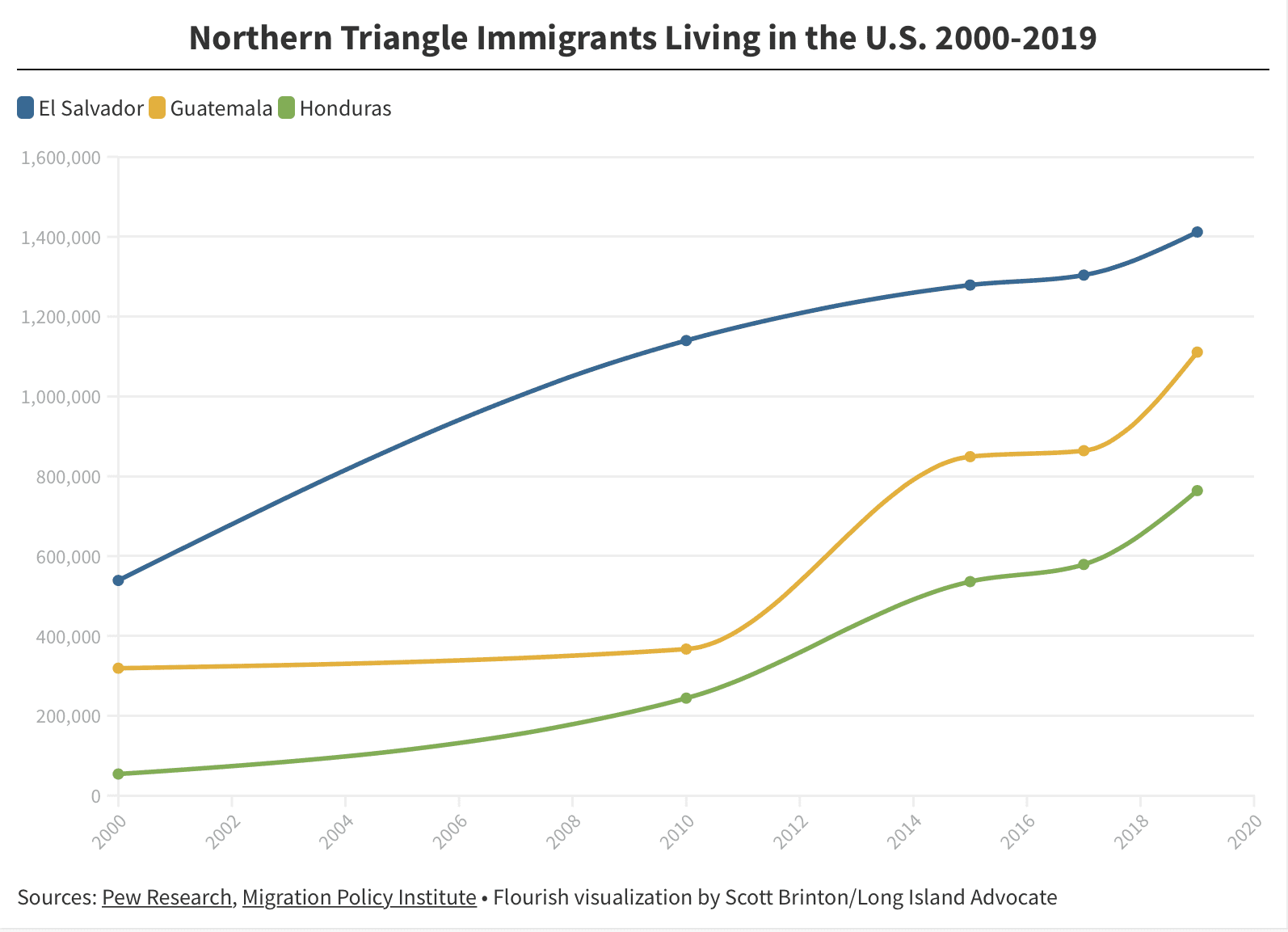

Not only does Guerrero know the game, but also he understands the difficult circumstances that many NYSLA players have endured at early ages. Many are from Central America, in particular the Northern Triangle, comprising Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, just south of Mexico. It is at once a beautiful, family- and neighborhood-centered region of the world, but because of civil wars, Cold War proxy fights, endemic poverty, gang warfare and narco-trade violence, millions of law-abiding refugees have been forced to flee for the relative safety of the U.S., Mexico and other countries over the decades, according to the United Nations. The Council on Foreign Relations estimates that 2 million have left the three nations since 2014 alone.

Ena Sanchez, 27, a NYSLA volunteer coach and the club’s secretary (its only paid position), arrived in Hempstead from Honduras in 2014, at 19, with her 3-year-old son, Kerlin. She spoke no English, but came to reunite with her mother and father, whom she had not lived with since she was 7. Her parents had come to Long Island to work as cooks in restaurants and save enough money to send for their son, two daughters and grandson. Ena had stayed with her grandmother most of the time during the 12 formative years that she was without her parents.

“There were many things we had to go through in life,” said Sanchez, who is now fluent in English. She noted that she has no memories of her parents growing up.

At first, she said, she was wary of coming to the U.S. As a single teenage mother, the journey through Guatemala and Mexico with a young child would be long and arduous, possibly dangerous. But, she said, she knew she had to seek a more stable life up north for her son, and in Hempstead, she said, she has found one. “We can do better than in our country,” she said. “All the opportunities, you can’t get that in our country — the school, the sports, the security.”

Finding friendship on the field

Kerlin, who is now 12 and attends the St. Joseph School on Franklin Avenue in Garden City, is a central figure on the Halcones, or Hawks, a NYSLA Boys-Under 12 team, for which he plays goalie and midfielder. “At first,” Kerlin said, “my mom convinced me” to play. “Then I started liking it. Then I loved it.”

Ena had played soccer since she was a kid, mostly for fun, and then for Hempstead High School for one season upon her arrival in the U.S. She also taught gymnastics in Garden City for four years.

Outside of NYSLA, Kerlin also takes part in the Olympic Development Program, an advanced soccer training program that requires a great deal of time. “Literally, every day, it’s soccer,” said Ena, who had studied at Queensborough Community College to become a medical assistant and is now taking law classes online through Universidad Politécnica de Honduras.

For many of the players, soccer is an escape. “It kind of relieves you of all your stress, and you forget about everything when you’re playing,” said Joel Guevara, 11, of Uniondale.

Joel Zuniga, 11, of East Meadow, said he joined NYSLA because of his father’s love of the game. “I watched soccer. My dad watched soccer. My dad always played soccer. I just decided” to join, Joel said.

For 12-year-old Victor Aguilar, a striker and midfielder and the Halcones’ top scorer, soccer is about the friendships. “It’s entertaining, he said. “If you’re bored, you can just play outside with your friends.”

“Sport,” Guerrero said, “takes you to the next level . . . It gives you commitment to life. It teaches you how to win and to lose.”

For more information about the New York Soccer Latin Academy, email nysla11550@gmail.com.