By Blake Waldron

On Dec. 28, 2018, 28-year-old Kevin Rollins, an inmate at the Nassau County Correctional Facility in East Meadow, died of a fentanyl overdose after he was found in cardiac arrest in his cell, where he was awaiting sentencing after violating the terms of his deal with Nassau’s Drug Treatment Court following a 2016 arrest.

Rollins’ death trigged a New York State Commission of Correction investigation. In a Jan. 5 report on Rollins’ death, the agency found there had been 237 drug contraband seizures at the Nassau County jail in a 45-month period from the start of 2016 to the summer of 2019.

The NYSCC also found the jail’s search-and-seizure policy before Rollins’ fatal overdose was lacking. “The Medical Review Board has found that, due to inadequate facility policies for searches, the facility failed to take adequate precautions to [ensure] the elimination of contraband in the building that housed Rollins prior to his death,” the NYSCC report stated.

Despite the large number of drug seizures and the death of an inmate, there is currently no pending legislation that would force a policy change at the jail, according to Christine Geed, communications director for County Executive Laura Curran, a Democrat from Baldwin.

“The fact that you’re finding contraband doesn’t mean that you have a contraband problem,” said Michael Golio, a captain in the Nassau County Sheriff’s Department.

Correctional facility officials conduct searches at least twice a year and are required to conduct a search following the death of an inmate. According to Golio, additional searches are at the discretion of a supervisor.

“We’re finding contraband because we’re aggressively and actively searching for it, and I think that people should take some comfort in that,” Golio said.

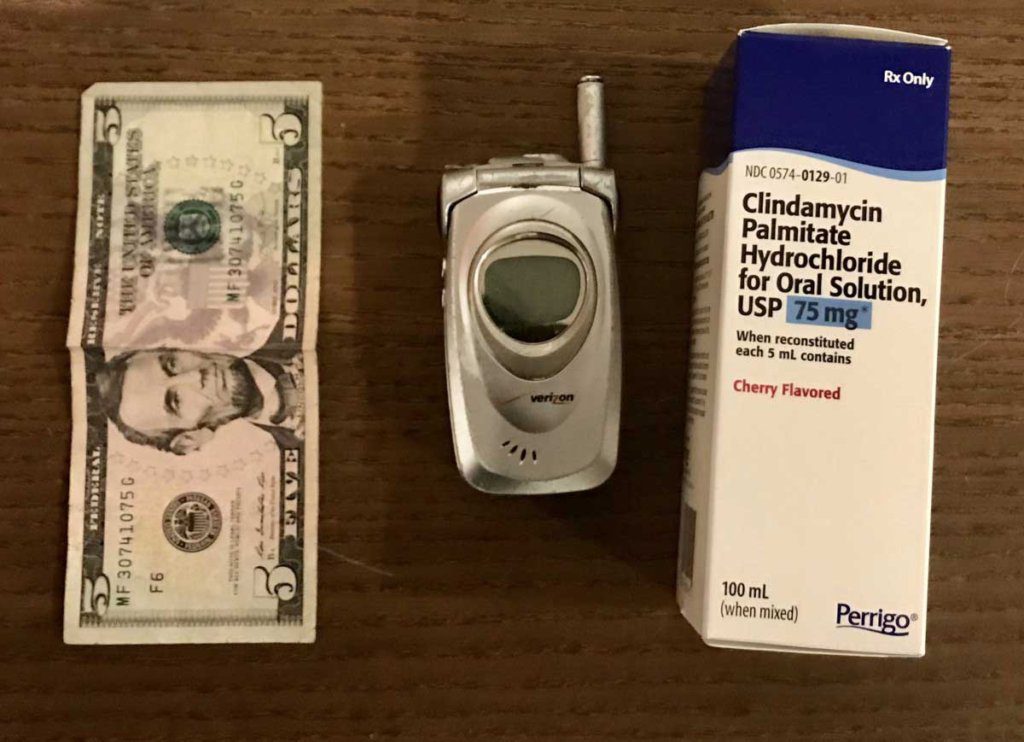

Paper money, a cellphone and prescription medicine are all considered contraband, according to the jail’s website.

Tek84 intercepts, inmate body scanners, were recently purchased for the jail. The scanners, which can conduct a full-body scan in 3.8 seconds, allow one staff member to scan up to 180 people an hour, according to the Tek84 website.

Ron McAndrew, a former Florida state prison warden and current corrections consultant, helped run prisons for more than 40 years. He says a small number of corrections officers bring contraband into jails.

“Ninety-five percent of the people working in prisons are incredible people,” McAndrew said, “but there is that small amount that fall through the cracks. In that 4 to 5 percent I’m talking about, they see these opportunities to turn it into a business, where they can make more money smuggling quaaludes.”

He noted that controlling contraband begins at the top of a jail’s administration.“It’s something that the wardens have to control. They’re in charge of the institution,” he said.

One reason an inmate may resort to contraband is mental illness. According to the Treatment Advocacy Center, an Arlington, Va. organization dedicated to providing community-based mental health treatment, about 20 percent of inmates in jails suffer from serious mental illnesses. As of May 5, there were 188 inmates at the Nassau County jail, which means that using the advocacy center’s estimate, around 38 of the facility’s inmates could have a serious mental illness, which does not include those who might develop mental illness during their time behind bars.

This often leads to a path of drug addiction while imprisoned as a way to cope with their experiences in jail.

Some advocates, including Jayette Lansbury, the National Alliance on Mental Illness chair, say anyone who has been incarcerated will have a type of trauma. “If you’ve ever been locked up, it’s called PTSD: post-prison traumatic stress disorder. The trauma and the stress of being inside, if you have family outside, [it’s] worrying about your family and worrying about your future,” Lansbury said.

She said she believes the system needs to change to rehabilitate those in need. “We know it’s not the best place for people. Those with mental illness deserve treatment, not jail. We believe in help, not handcuffs,” Lansbury said.

Barbara Allen, the founder of Prison Families Anonymous, a non-profit organization based in Hauppauge, in Suffolk County, shares that sentiment. “They make visiting hours very difficult, so it is hard for us as families to see our loved ones. So losing that kind of support can be very draining and make these people act in a way that they may not under usual circumstances,” Allen said.

Allen said there used to be a garden and an educational program run by East Meadow teachers at the Nassau County jail. Neither has existed for a number of years. Allen does not know for certain why they were cut, but thinks it’s because the correctional center’s culture has hardened over the years.

“They’d rather completely isolate those that are inside from those on the outside,” Allen said.

The executive director of New Hour for Women and Children-LI, Serena Ligouri, said that before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, her group was close to beginning programing at the correctional center. When the pandemic is over, Ligouri said she is excited to work with the sheriff’s office in returning programming to the jail.

“I think it’s going to be a huge cultural shift that I’m hopeful will happen in the Nassau jail right now,” Ligouri said. “I’m hopeful that when we’re able to go in and provide a pathway to work together with the Sheriff’s Department.”

Ligouri said that opting for a system of support and understanding, rather than the culture of discipline, could make a positive difference for all parties in the future.

“There is such a sense of relief,” she said. “The look on their face when they see that you’re there to help them. I think it’s a misnomer that people who end up incarcerated don’t want positive futures and that they aren’t trying hard to create safe spaces for themselves and their families. We just need to give them the opportunity to do it together.”