By Paola Cardenas

Editor’s note: Part one in a series on Long Island housing.

New York State Gov. Kathy Hochul spoke on details of her 2024 fiscal year budget during a news conference in Patchogue March 12. When discussing her Housing Compact, she reminisced on her parents’ many homes, explaining they started in a trailer park, then graduated to a two-bedroom apartment, which eventually led them to Sears kit home. As more children were born, her parents upgraded their homes and continued to do so after their children had moved out. Her desire, she said, is to ensure that all New Yorkers can afford a place to live.

Much of the governor’s proposed housing plan, which she proposed last January, was removed from the 2024 state budget, however. Among the provisions that remained were $391 million for an Emergency Rental Assistance Program and $50 million for low-income families to repair their homes, as well as funds for lead removal in homes built before 1980.

Long Island was once considered by many to be an affordable region of the state to purchase a home with a yard. Unlike New York City during the 1960s, there was room to breathe, activities to relax, quality K-12 education and roadways for easy travel. Today, much of this is still true, but one of Long Island’s most pressing challenges is housing affordability. The cost of renting or owning a home has become prohibitive for many.

Some 51% of New York renters are “rent-burdened,” meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on rent. Meanwhile, housing and rent prices have increased anywhere from 40% to 80% since 2015.

Hochul, a Democrat, noted that in the past 10 years, New York created 1.2 million jobs, but only 400,000 new homes were built. In her 2023 State of the State address, Hochul said she wanted 800,000 new homes constructed over the next decade to fill the housing shortage and potentially mitigate housing prices. The plan included:

- Statewide housing targets.

- Infrastructure and planning funds.

- Transit-oriented development.

- The removal of obstacles to housing approval.

- Incentives to build and rehabilitate housing.

- A program to reduce lead exposure in high-risk areas.

- Greater control for local governments of dangerous abandoned properties.

- Financing for home repairs in communities that have high levels of low-income homeowners of color and homeowners who are in distress.

- Increased funding for the state’s Tenant Protection Unit to open additional satellite offices.

The governor’s plan sparked controversy among Long Island officials who are figuring out how to tackle the housing crisis. Town officials, non-profit leaders, state Assembly members, social service workers, water and fire officials, school board trustees, and other local elected leaders publicly addressed their support or concern over the plan for a range of reasons.

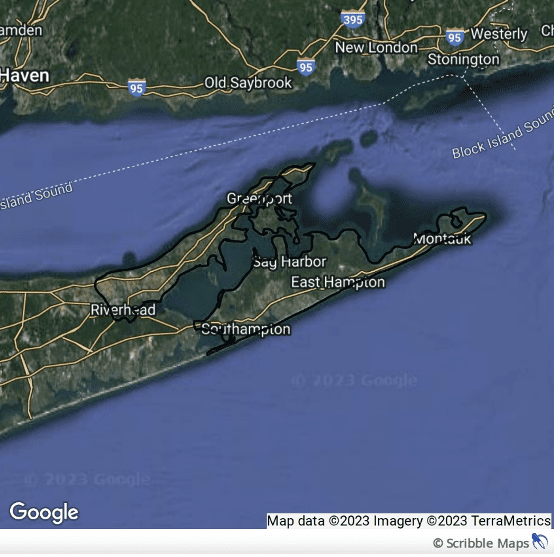

Michael Daly, a real estate agent at Douglas Elliman and founder of East End YIMBY, advocates for affordable community housing on Long Island’s East End, which includes East Hampton, Shelter Island, Southold, Riverhead and Southampton, among other areas on the North and South forks. YIMBY, which stands for Yes In My Backyard, uses social media and public rallies to promote awareness about the housing crisis and to educate the public on critical housing issues.

A common misconception, Daly noted, is that East End communities do not struggle with housing affordability, as many areas are considered affluent. In reality, he said, many local people are being priced out of the housing market.

“I felt like the most beneficial thing about [Hochul’s housing plan] was it was going to empower cities, towns, villages to rethink their zoning, which is primarily focused on single-family housing,” Daly said. “It was going to give them an opportunity to rethink their zoning in order to accommodate to the type of housing that people are looking for today.”

For 25 years, Daly has worked as a real estate agent, renting and selling houses. Ten years ago, he noticed something started to change in the local housing market. The East End’s heritage industries of farming, fishing and tourism by the Shinnecock Nation First Peoples were jeopardized by the housing market. Locals started to leave their communities for ones where they could find affordable housing.

“If we only leave our development to market forces and don’t step in and protect our local community, culture and heritage, it’s going to die,” Daly said. “The very thing that attracts people to come here, if we lose that, it will have a terrible impact.”

Ian Wilder is executive director at Long Island Housing Services Inc., an organization that serves as Long Island’s private fair housing advocacy and enforcement agency for Nassau and Suffolk counties. Wilder supported the governor’s plan, as he saw it as a step in the right direction toward solving the housing crisis. The plan caused an uproar over a variety of disagreements, though, which Wilder said was mainly over methodology or ideology.

After earning his bachelor’s in business administration from Hofstra University in 1987, he did social justice work with his wife during his free time, which led him to housing counseling work at Long Island Housing Services. “The ability to come here allowed me to merge my interest in social justice with my work life,” he said. “That’s why I came here to work and dedicated to the mission.”

Mike Florio, CEO of Long Island Builders Institute, a trade association that represents builders, suppliers, tradespeople and developers, agreed with the governor’s Housing Compact, saying, “The building industry understands the dire need for more housing on Long Island, especially affordable housing.”

Laura Harding, president of the Syosset-based ERASE Racism, an organization whose mission is to expose racial issues and advocate for equity and inclusion, agreed that affordable housing is needed, in part to help break the Island’s longstanding cycle of segregated housing.

“We feel it could have gone a long way in focusing more on affordability and providing more money to infrastructure,” Harding said, “but we did feel that it would be a start to ending exclusionary zoning, which led to Long Island being the 10th most segregated place in America.”

“If we only leave our development to market forces and don’t step in and protect our local community, culture and heritage, it’s going to die. The very thing that attracts people to come here, if we lose that, it will have a terrible impact.”

Michael Daly, Founder of East End YIMBY (Yes in My Backyard)

Not all Long Island leaders, however, agreed with the governor’s plan. Town of North Hempstead Supervisor Jen DeSena, a Republican, was among those to denounce it. “I’m glad Governor Hochul has finally come to her senses and listened to myself and other local elected officials who stood up in the face of this ridiculous plan,” she said after the Housing Compact was removed from the state budget.

DeSena joined Town of Oyster Bay Supervisor Joseph Saladino and Town of Hempstead Supervisor Don Clavin, both Republicans, on several occasions to speak against the governor’s plan, alongside school board officials, environmentalists, homeowners, utility leaders and first responders. She said she believed the governor’s plan would have overridden local zoning and imposed unfunded state mandates without offering local government officials a chance to advocate for those they represent.

“I hope that going forward the governor will take the opportunity to actually seek input from local government before presenting another ill-advised plan that disregards the concerns of those who actually live in these communities,” she said.

In a letter addressed to Town of Oyster Bay residents, Saladino said the governor’s plan “would create high-density housing zones around every Long Island Rail Road station and allow for apartments to flood single-family home neighborhoods.”

At the same time, Saladino said, the plan would have caused overcrowding in local schools, strained police and emergency services, harmed the environment and silenced local government officials.

Clavin said he had received multiple emails, comments on social media, phone calls and paper mail from residents concerned about the plan. “Hempstead Town,” he said, “is a desirable place to live because it remains a quiet suburb, even with 800,000 residents. We’re not Queens. We don’t want to be like Queens. We’re proud to be a suburb because it’s the best place to live, work and raise a family.”