By Michael Richardson

Part seven in a series on the planned Las Vegas Sands Casino at the Nassau County Hub.

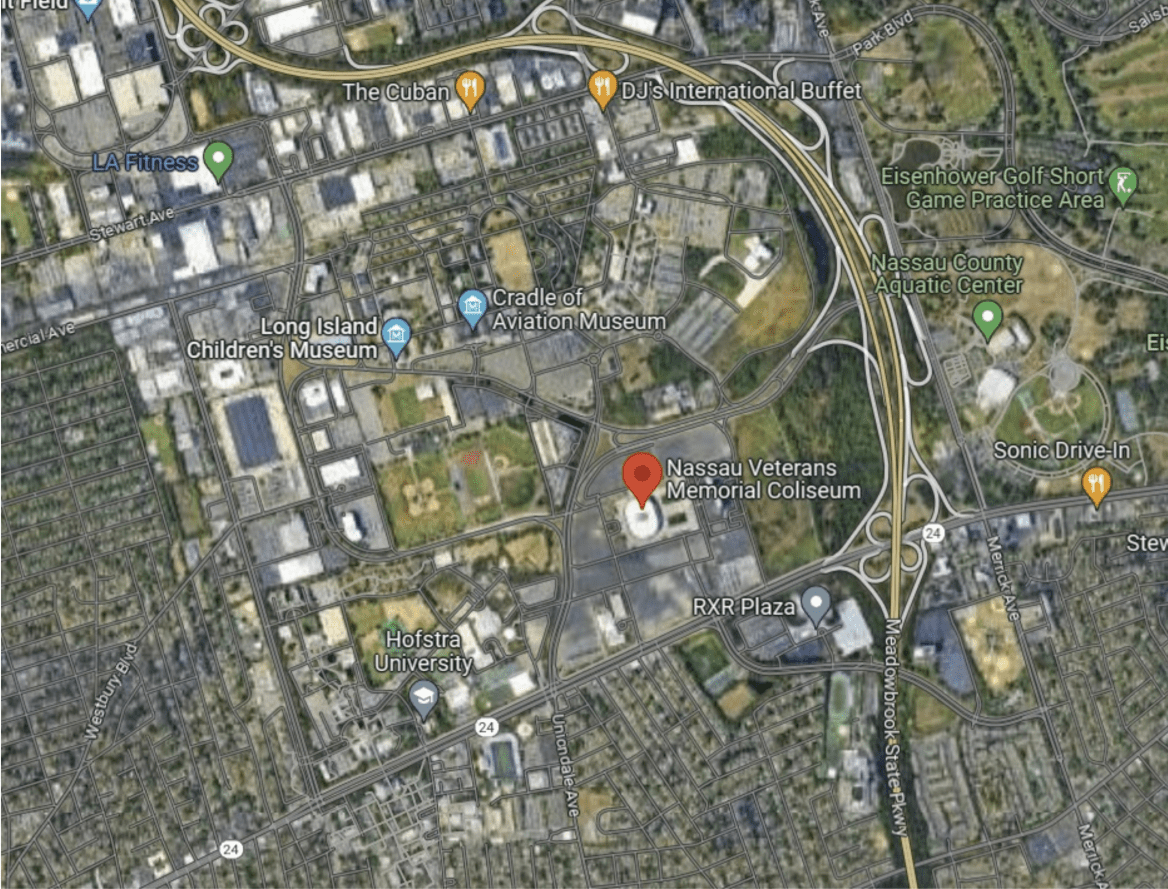

Earlier this year, Las Vegas Sands announced plans to construct a multi-billion-dollar project at the Nassau Coliseum site in Uniondale, including a casino. The area, once inhabited by the New York Islanders before the team moved to UBS Arena in Elmont, hosts the New York Riptide, a lacrosse team, and the Long Island Nets, a basketball squad. With the multinational corporation recently acquiring the lease to the land, the stage has been set for a debate with Albany over whether it will obtain one of three coveted gambling licenses in the state.

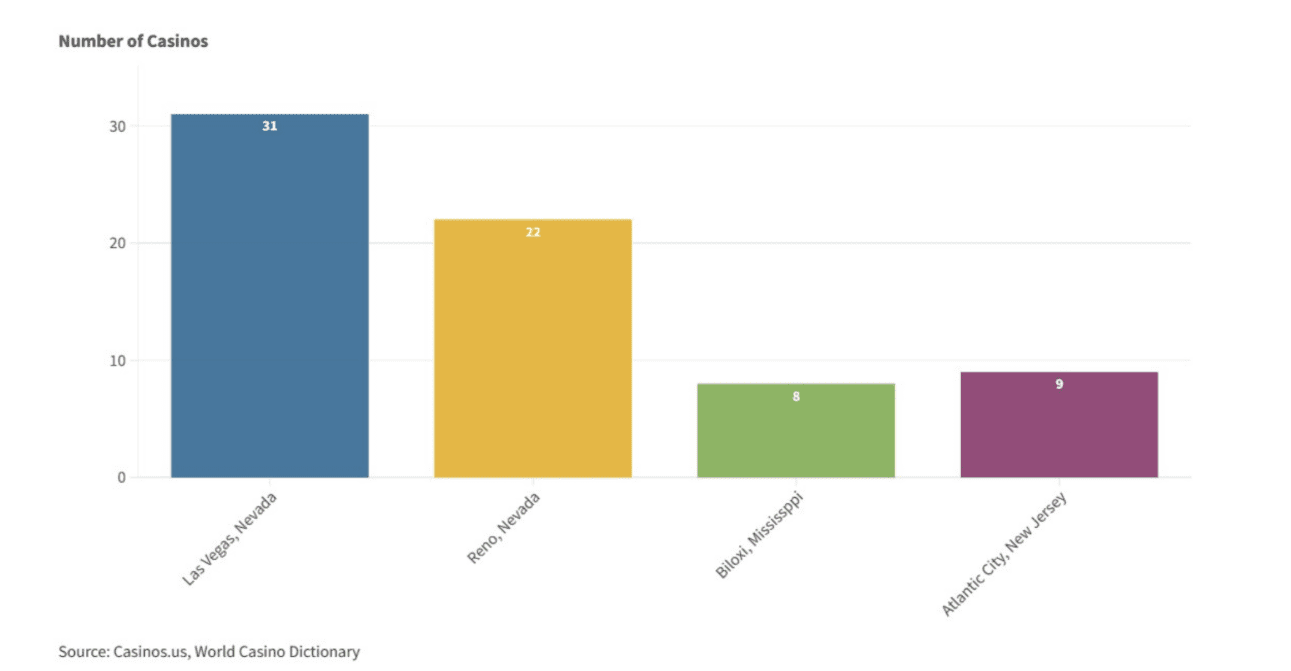

The Sands project would serve as a test of whether a casino of this magnitude could survive on Long Island, particularly in the wake of recent casino closures in nearby Atlantic City, from Revel to the Trump Taj Mahal, and particularly given that the Island is already home to an established casino, Jake’s 58 in Islandia, with a thousand electronic gaming machines.

Does Las Vegas Sands Corp. have what it takes to create a financially viable casino near the birthplace of suburban America?

For development alone, the Sands resort project at the Nassau Hub would cost roughly $4 billion. The corporation recently recorded revenue of $2.1 billion in the first quarter of the year, surpassing many estimates.

According to Statista, the gross gaming revenue of casinos in Nevada in 2021 was about $13.4 billion, which was greater than the $4.7 billion generated in New Jersey. Operating a casino requires a massive outlay in labor costs, license fees, utilities, security, rent and more. According to Newsday, if a casino were built, Las Vegas Sands Corp. would be required to pay $96.3 million annually to the county in rent, taxes, public safety payments and community benefits alone.

The Las Vegas Sands project, if approved, would be a test whether a casino of this magnitude could survive on Long Island.

For the casino at the Nassau Coliseum site to break even, it would have to make more money than it costs to maintain. According to Gambling Riot, the average gambler in 2011 lost around $528 to casinos, making the average daily loss slightly less than $1.45. If 16,000 gamblers were to visit the Uniondale casino daily — the seating capacity of the Nassau Coliseum — and each visitor were to lose $10 on average, that would give the casino $160,000 in daily revenue. That would equate to $58.4 million each year, which is nearly $38 million less than the annual payments the corporation would have to make. Thus, Las Vegas Sands would likely need to rely on revenue from its other ventures at the Hub, including its proposed restaurants, or hope that the house generated enough cash from visitors to profit.

A 1998 study of the regional economic impacts of casino gambling found that the long-run impacts of sustained casino operation are generally positive. “Even if casino gambling fails, there is no indication that an already depressed area would be any worse off,” the study reads.

The proposed casino at the Nassau Coliseum site would likely receive heavy traffic, according to estimates. At the same time, Hempstead Turnpike is one of the deadliest roads in New York, with Newsday recording 19 fatalities between 2016 and 2020. Additional traffic could increase the risk of fatalities, impacting the number of people entering the casino, and thereby worsening the Sands’ profit margins.

Local reaction to the Sands casino proposal

A source with knowledge of the situation who requested anonymity said the coliseum site has caused a political stir for decades, with myriad proposals that have not stood the test of time, from the 60-story Lighthouse Project to a minor-league baseball team.

The source noted that, financially, Nassau County would likely stand to gain from the development of a casino, adding that Las Vegas Sands would bring jobs to the local area. This is why Nassau County Executive Bruce Blakeman has said he supports Sands’ development of the project.

In contrast to Blakeman, the Hofstra University administration has been a vocal detractor of the project.

“A casino at the Hub is not about the future, and it would not be an engine for economic and social prosperity,” Hofstra University President Susan Poser wrote in a Newsday op-ed earlier this year. “It would be dangerous for adjoining neighborhoods, and create a nightmare of traffic and pollution, not to mention anti-social behaviors that often crop up around casinos.”

Ryan Pagano, a Hofstra audio/radio production and studies major, said the proposed construction site has been “a glorified money pit for the better part of 50 years now,” and he could see Las Vegas Sands bringing in a great deal of money with a casino, adding that the corporation has “proven successful in a lot of other areas in this country.”

At the same time, Pagano expressed concern that the casino could increase violence locally and deter parents from sending their children to Hofstra.

One of parents’ first impressions of Hofstra on their college visits would be of a casino, as it would be located across the street from the university. “There are probably going to be a lot of people that think that they don’t want their kids to be associated with that,” Pagano said.

In an interview with WRHU earlier this year, Village of Westbury Mayor Peter Cavallaro said he believes Las Vegas Sands would generate a “tremendous amount of money” from the casino, but he expressed concern at the long-term social and economic impacts.

The National Center for Suburban Studies at Hofstra University released a paper arguing that casinos fail to reinvigorate local economies and that the proposal by Las Vegas Sands goes against the aspirations of a “technology corridor” in the county. The paper cites a 2002 report from the St. Louis Federal Reserve that states local businesses could be impacted if the casino’s main clientele resided in nearby areas.

If the casino at the coliseum site were to be built, Las Vegas Sands has indicated that it would involve local businesses.

The co-facilitator of the Greater Uniondale Area Action Coalition, Jeannine Maynard, said she thinks the Sands proposal would benefit the local economy.

“From a business-to-business perspective, it does stimulate the local economy in a big way,” Maynard said. “Our local businesses, I believe, have the talent to rise to that, and so I see that as being sustainable.”

Could a Hub casino go under?

When the Revel Casino Hotel in Atlantic City closed in September 2014 after two and a half years, more than 3,000 people lost their jobs. The $2.4 billion project was one of four casinos to shut down in the coastal hub that year.

The upfront costs associated with casino and resort development may make the proposal at the Nassau Coliseum site unprofitable in the short-term, but it could over the long term prove to be financially viable. Las Vegas Sands Corp. would need to find a way to offset annual costs with increased profit margins likely not just through the casino but other resort features as well.

Hofstra University provided the following statement regarding the community impact of a casino in the Nassau Hub:

“The Nassau Hub is not an appropriate location for a large-scale casino development because of the density of college and high school students in the immediate area. Between Hofstra University, Nassau Community College and the Kellenberg School, there are more than 30,000 students across the street from the proposed development, and more than 60,000 students ranging from preschool to college in a six-mile radius. Studies show that young people are especially vulnerable to gambling addiction. A casino would also create dangerous conditions, including increased crime, traffic congestion, and water and air pollution, for surrounding communities. Whatever short-term financial gain Las Vegas Sands is promising, it will come at the expense of a more strategic and community-oriented plan to develop this valuable piece of property to benefit the long-term future of Nassau County and its residents.

“This is a huge plan with significant risk of impact, and there are many, many factors that are very difficult for the community and the surrounding area,” Maynard said.