By Melinda Rolls

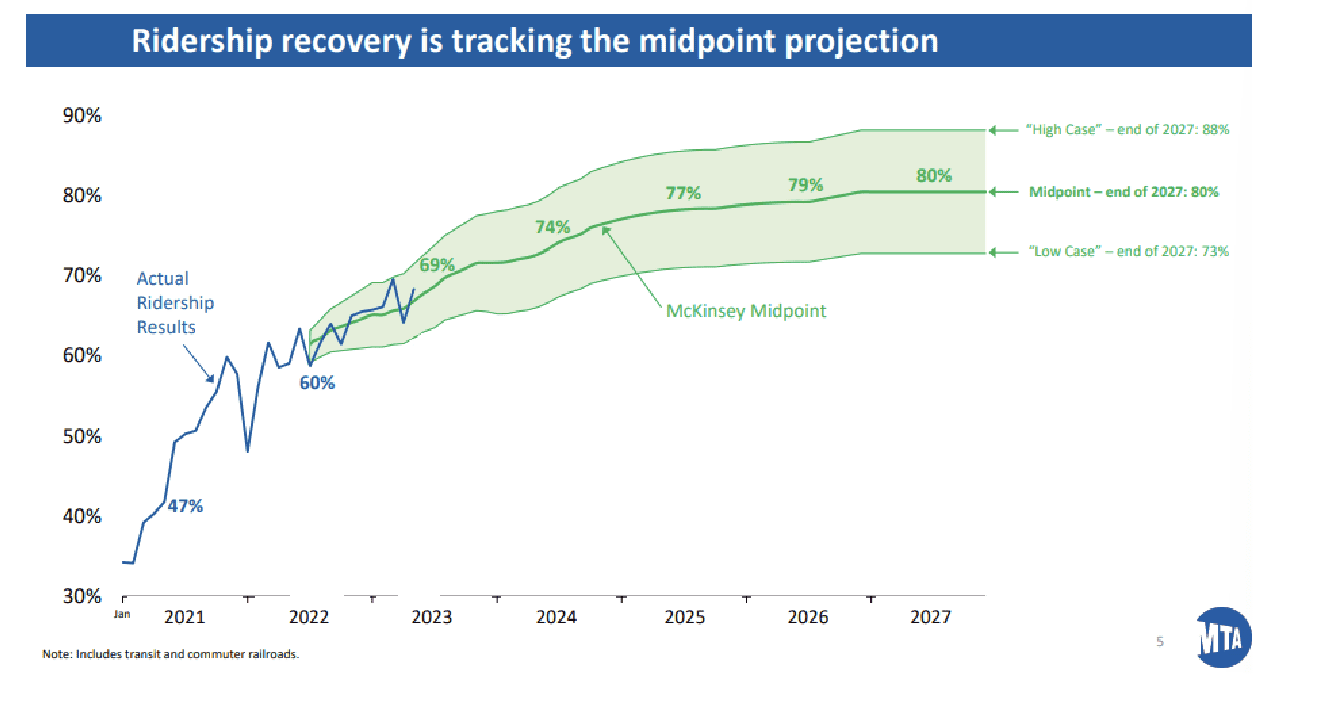

For the first time in two decades, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority is projecting a balanced budget for five consecutive years, MTA officials said at an Oct. 19 news conference.The preliminary five-year financial plan through 2027 aims to pull the authority out of financial distress.

According to an annual financial report by the office of New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, new funding found in the 2024 state budget has balanced the expected deficits this year and in the next four years.

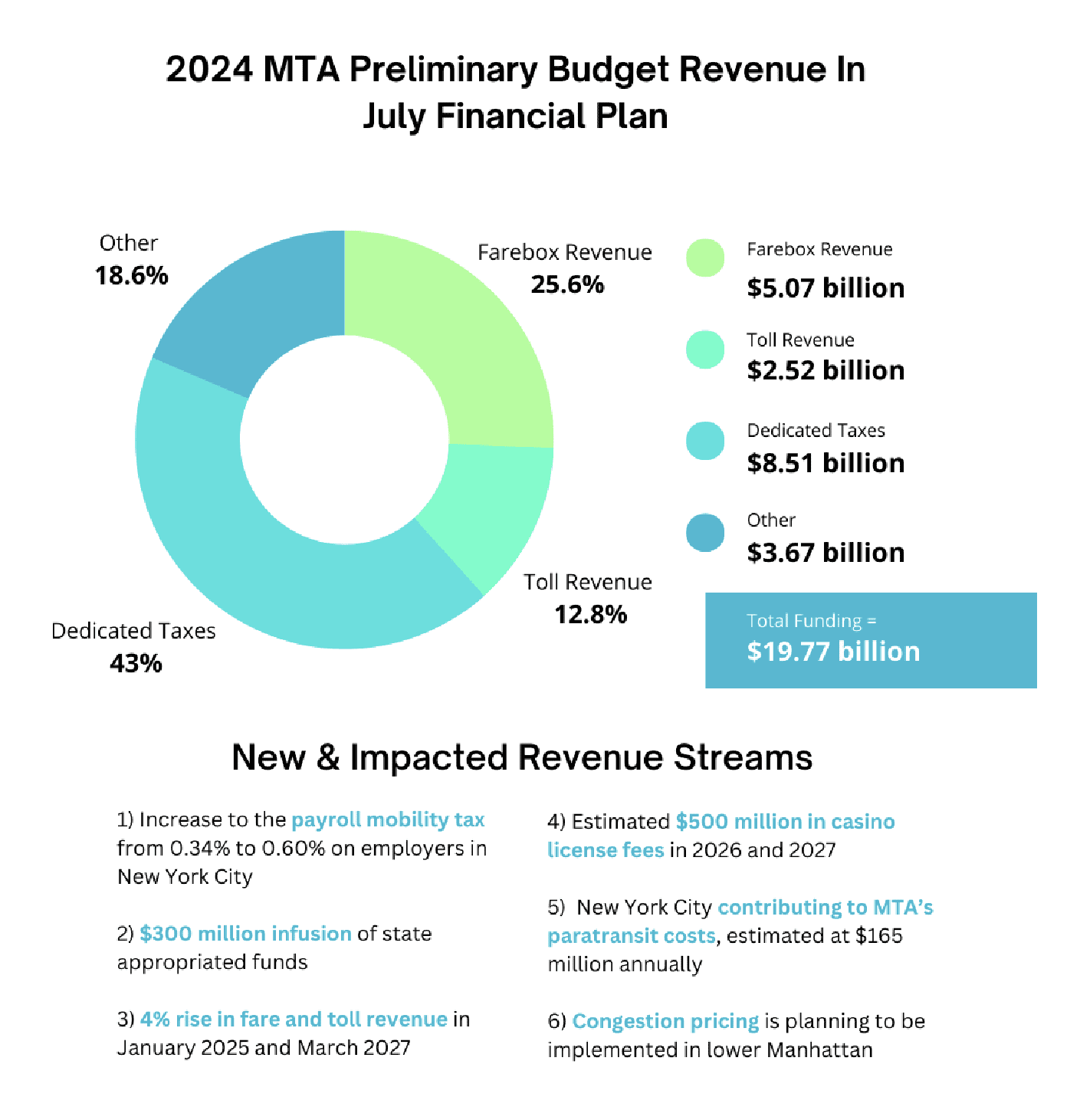

A main contributor to closure of current and future budget gaps is an increase to the payroll transportation mobility tax on employers in New York City, with the MTA anticipating $1.1 billion a year from the increase. Early this May, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul approved a State Senate bill that increased the top rate for the tax from 0.34% to 0.60% for employers doing business within the Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District, or MCTD.

The district is divided into two zones:

• Zone one includes Bronx, Kings (Brooklyn), New York (Manhattan), Queens and Richmond (Staten Island) counties.

• Zone two comprises Dutchess, Nassau, Orange, Putnam, Suffolk and Westchester counties.

MTA commuters will see a rise in fare and toll prices in the next few years to supplement the new funding. The MTA’s latest financial plan assumes fare and toll revenue increases in January 2025 and March 2027, representing an overall 4% hike in fares and tolls.

The January 2025 pricing is expected to generate a $299 million increase in annual MTA fare and toll revenues, and the March 2027 pricing, $325 million in annual revenue.

The MTA will also benefit from a one-time $300 million infusion of state funds in 2023. Additional fiscal relief will come from the transfer of responsibility for funding paratransit services to New York City, and the dedication of up to $500 million in casino license fees from three New York state casinos that are expected to be constructed in 2026 and 2027.

Congestion pricing is essential to fund $15 billion of the MTA’s 2020-24 capital program. The plan would charge drivers in Lower Manhattan a toll at or below 60th Street, except on major highways.

“Half of the congestion pricing is slated to help fund the Capital Program, which pays for a lot of big-ticket projects we’ve been talking about,”said MTA Chairman Janno Lieber at the news conference.

At an Oct. 2 Traffic Mobility Review Board Public Meeting that was streamed online, three potential congestion pricing options were discussed, ranging from $4 to $7 during the day, while the toll would be reduced 50 to 70% at night.

“Our job here is to help the MTA provide the money in as equitable a way as possible, and do it at the lowest cost,” said Traffic Mobility Board Chair Carl Weisbrod during the meeting.

Lawsuits and a public outcry over congestion pricing, however, have delayed the plan’s execution. New Jersey is suing the Federal Highway Administration for approving the toll program, concerned that the program will impose a financial burden on Garden State residents.

The lawsuit argues that New Jersey drivers who work in Manhattan should not have to pay to fund toll program, and it points to findings of an environmental assessment by the MTA that concluded motorists driving around the tolls might increase traffic and pollution in New Jersey. The suit calls for an intensive study to determine if the pricing plan would harm people in lower-income communities.

Ridership on MTA transportation lines appears to have increased significantly during off-peak hours. “We’re seeing huge ridership in hours off-peak, bigger than pre-Covid,” said MTA Chief of External Relations John McCarthy.

The Long Island Rail Road has seen an especially high ridership rate this month. “Last week was the highest average weekday ridership since the pandemic, averaging 231,000 customers a day,” said acting LIRR President Robert Free. “We also had our highest ridership day since the pandemic last Thursday, approximately 249,000 customers.”

With increased revenue, MTA officials said they hope to make several changes to the transit system over the next five years, including a $54.8 billion investment in subways, buses and commuter railroads.

After losing $285 million to fare evasion last year, the MTA plans to install fare gates, motorized plexiglass glass doors that make it harder to evade paying fares. According to an NBC report, the authority has used surveillance software with artificial intelligence to spot people evading fares to determine where fare gates are most needed.

The MTA also plans to add elevators to 70 more stations, which would make 95% of stations accessible to people with disabilities by 2055. The promise to add the elevators came after two class-action lawsuits over a lack of accessibility in 2017.

Funding is also expected to go to the LIRR to increase seating on trains, with a plan to purchase up to 17 cars for shorter trains. As well, the MTA plans to improve the signal system for LIRR trains, which enforces safe spacing between trains and speeds. The capital program report confirms that many signals date back to the 1950s and ’60s.