By Damali Ramirez

Scrolling through the Walgreens’ Covid-19 vaccination homepage recently, 71-year-old Rase Denny, a retired nurse who worked for more than 30 years at Winthrop-University Hospital in Mineola, had no luck finding an appointment near his Uniondale home. After weeks of having his name down on the waiting list and searching at different locations, Denny received a phone call about an available appointment.

Walgreens “didn’t have anything, and then I got a call that somebody didn’t show up, and at that point, I was able to automatically book my second appointment 30 days after,” he said.

After months of waiting, 71-year-old Rase Denny, of Uniondale, was able secure a Covid-19 vaccine appointment through Walgreens. // Photo by Damali Ramirez/Long Island Advocate

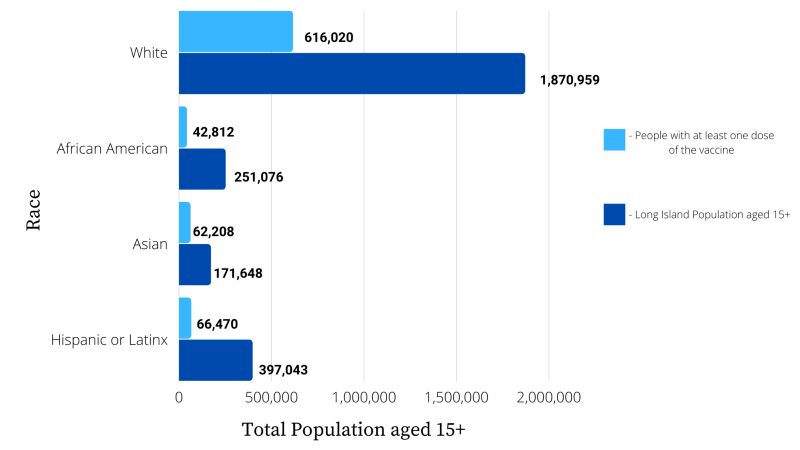

Denny is among the roughly 43,800 Black residents on Long Island — out of a total population of more than 250,000 — who have received at least one dose of the vaccine, and now he faces challenges securing an appointment for his sister.

Across the nation, the vaccination rate among communities of color has been significantly lower than in white communities, despite the higher Covid-19 infection rates in such areas.

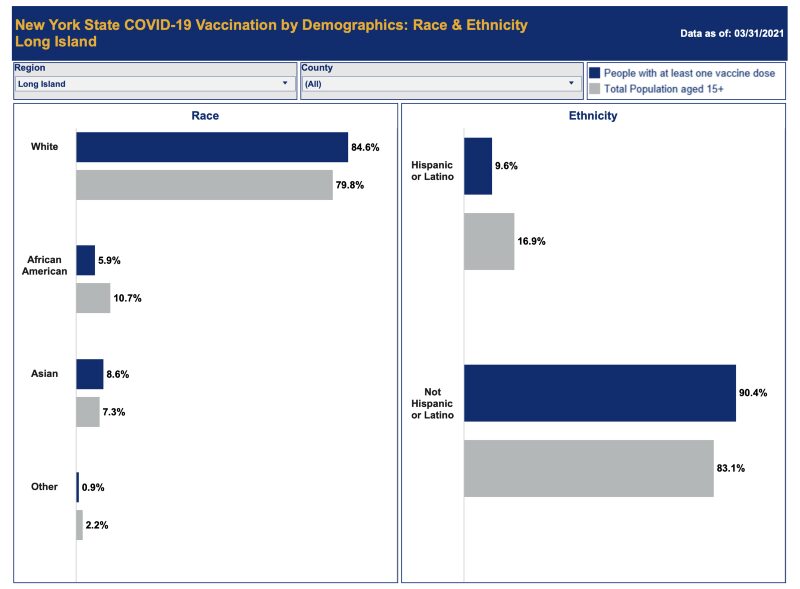

On Long Island, of the nearly 811,000 people who have received at least one dose of the vaccine to date, 84.6 percent have been white, including Hispanic people; 8.6, Asian; 5.9 percent, Black; and .9 percent, other, according to New York State Department of Health data by race. The Census Bureau definition of white includes anyone of European, North African or Middle Eastern descent.

The state further parses out data by ethnicity. According to this data set, 9.6 percent of Hispanic or Latino people on Long Island have received at least one dose of the vaccine.

White people — not Hispanic or Latino — comprise about 63 percent of Long Island’s total population, but to date, they have received 75 percent of Covid-19 vaccine does. Meanwhile, the percentage of Black people receiving one dose is roughly 5 points lower than their percentage of the population, and for Hispanic people, it’s more than 7 points lower.

That is, non-Hispanic white people are overrepresented among those receiving their first dose of the Covid-19 vaccine, and Black and Hispanic people are underrepresented, while Asians are slightly overrepresented.

Dr. Jeffrey Reynolds, the president and chief executive officer of the Garden City-based Family and Children’s Association, said he was not surprised when the data showed lower vaccination rates among Black and Hispanic communities, noting past healthcare disparities between white communities and communities of color.

“I think what Covid initially did was it exposed all the fault lines that have been around since the beginning of time and made them clearer,” he said. “There’s a number of reasons particular to Covid. The disparities were there, but some of them relate to the prevalence of pre-existing conditions, and some of them relate to essential workers and the jobs they’re doing.”

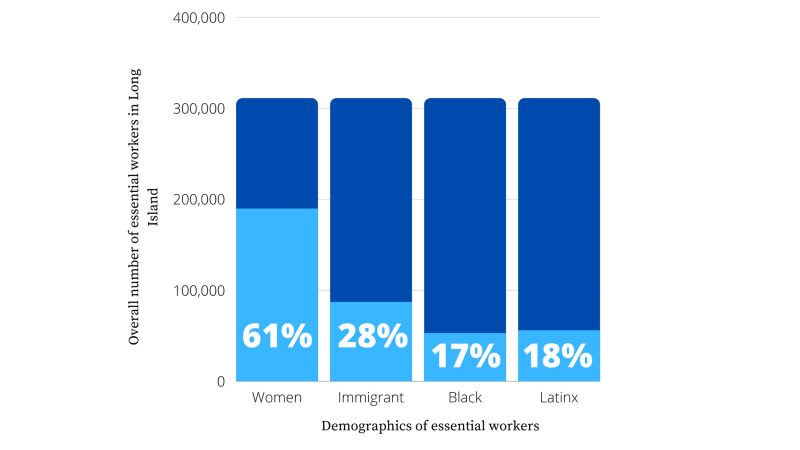

According to the Fiscal Policy Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research institute, Long Island has roughly 311,000 essential workers; 11 percent of them support their families on low-incomes, with a family of four earning less than $53,000 a year. Women, immigrants and Blacks are overrepresented among essential workers. Roughly 61 percent of women, 28 percent of immigrants and 17 percent of Black people are considered essential workers.

Reynolds explained that Black and Hispanic residents are more likely to live in tightly cramped homes and use public transportation, which leads to higher infection rates of communicable diseases, including the coronavirus.

Vaccine hesitancy

Experts like Reynolds believe low vaccination rates can be partly explained because of vaccination hesitancy. “There’s a high degree of distrust in minority communities of the healthcare system, vaccines, government,” he said, “and there’s a lot of history in place that reinforces some of that distrust.”

Although he believes the 1932–1972 Tuskegee syphilis experiment — in which Black men, without their knowledge, were given a placebo rather than a promised treatment to see what would happen if the venereal disease went unchecked — explains the distrust that many Black people feel toward the healthcare system, Reynolds does not think it is the only explanation. Healthcare disparities, coupled with a general lack of cultural competence among many healthcare workers, also are factors.

When Black and Hispanic residents go in for routine healthcare procedures, they often do not see workers who resemble them, and many times they need translators. If there are no available translators, non-English-speaking Black and Hispanic residents are put on a phone line. Reynolds said he believes these disparities reinforce the notion in their communities that healthcare has no place for them.

“I’ve spoken to a lot of folks who have a fundamental distrust of vaccines and the medical establishment, and I want to be careful because we don’t want to be in a position of calling anyone who has questions about the Covid vaccine an anti-vaxxer,” he said.

Reynolds said he believes health and government experts should have an open dialogue with people of color and answer fundamental questions about the vaccine. He also said vaccine pop-up sites should be located in accessible places that the community knows and trusts and enlist community leaders who can promote the vaccines.

“I think it’s very easy to say, well, the community doesn’t trust it, they don’t want it. Actually, there’s a lot of people who do. You’ve got to make sure that that access is there,” he said.

State Sen. Kevin Thomas, a Democrat from Levittown, represents the 6th District, whose constituents are a little over a third Black and Hispanic. His office, he said, has been increasing efforts to make the vaccine more accessible to people of color, hosting more vaccine pop-up sites, sending out mailings, and attending church and PTA meetings to spread the word about the vaccines and vaccination sites.

“In the very beginning, there was a lot of misinformation out there about the vaccine. We had to get over that hurdle,” he said. “We had to go into [Black and Hispanic] communities, talk about facts, and as more people got vaccinated that look like them, they start changing their mind.”

Fundamental vaccine issues

Aside from vaccine hesitancy, Reynolds said he believes that a lack of resources is also causing the low vaccination rates. Many Black and Hispanic residents do not have the technology or technological skills to navigate websites to schedule appointments.

“Lots of our employees talked about sitting with multiple screens opened up on their desktops, trying to get an appointment, as if they were buying concert tickets,” he said. “Not everybody has the time to do that. If you’re ambivalent about the vaccine, you’re not going to take the time to do that.”

Poor communities that are disproportionately Black and Hispanic are more likely to rely on public transportation and work two jobs to support their families financially. They are less likely to have the time to drive to far-away locations to get the vaccination and are restricted by public transportation.

When Reynolds recently received his vaccine at Suffolk Community College, he sat in the waiting area for 15 minutes and played on his phone. He then realized health and government experts are missing opportunities to tackle other healthcare issues, he said.

According to Feeding America, 1 in 17 people struggle with hunger on Long Island. The U.S. Census Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reported that roughly 26.6 percent of New York adults reported anxiety or depressive disorder symptoms this March.

Reynolds said vaccine waiting areas would be an ideal place for nonprofits to set up around the perimeter, offer people information about food, mental health issues and resources about substance abuse counseling. Research has shown mental health disorders, anxiety, depression and substance use have increased markedly during the coronavirus pandemic.

“We should be creating a catalog of the lessons learned, and there’s been more discussion about minority health over the past year than there has been in a long time, because those disparities were on display,” he said.

Scott Brinton contributed to this story.