A toxic groundwater plume in Bethpage is finally being cleaned up following the announcement of Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s removal plan on Dec. 21. The announcement followed decades of officials of the Bethpage Water District and surrounding water districts calling for action to contain and clean up the largest contaminated groundwater plume ever to threaten Long Island’s water supply.

“For decades, one of the most critical and intractable problems for Long Island was the toxic contamination caused by the Grumman and Navy sites. With this settlement — the largest of its kind in state history — we’re making the polluters pay and remedy the environmental degradation they caused,” Cuomo remarked in a statement.

To date, three treatment wells and 4,600 feet of piping have been installed, according to a fact sheet provided by Northrop Grumman, one of the two parties responsible for the plume with the U.S. Navy. Additionally, Michael Boufis, Bethpage Water District superintendent, said the district has also been partially reimbursed for the expenses needed to treat the contaminated water.

Cuomo’s plan calls on Northrop Grumman and the Navy to remediate the plume. Additionally, Northrop Grumman agreed to a Natural Resource Damages settlement of $104.4 million — the largest environmental settlement in New York State, according to Laura Curran, Nassau county executive. The settlement will be used by Grumman to advance clean up and reimburse water districts for the work to decontaminate the water.

“Finally, we have a comprehensive plan to treat the Bethpage plume,” said Adrienne Espositio, executive director of Citizens Campaign for the Environment, a statewide environmental and public health protection organization.

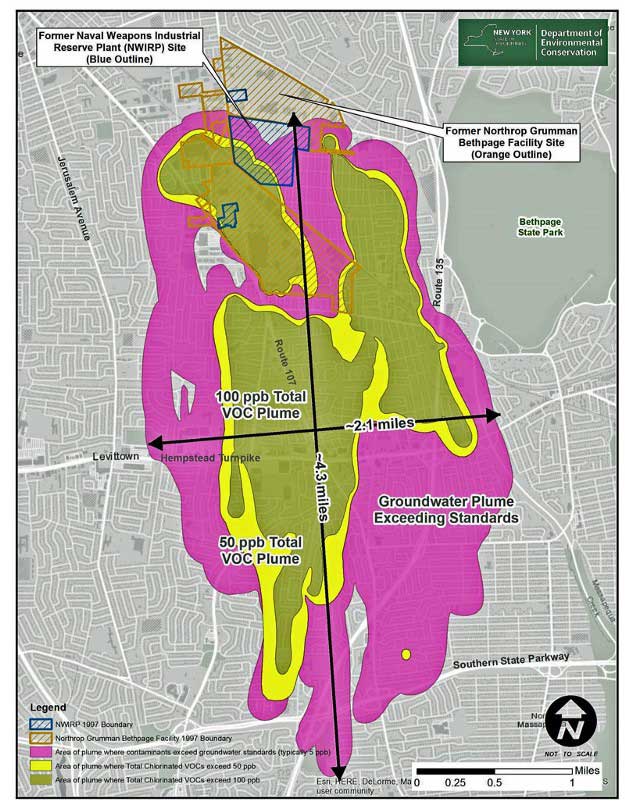

Spanning over four miles long, two miles wide and 900 feet deep, the plume affects water districts in Bethpage, Levittown and South Farmingdale, has reached Seaford, and is heading toward Massapequa. Monitoring wells have been drilled in residential areas in North Wantagh and northern Seaford to measure contamination.

The contaminated water contains TCE (trichloroethylene) from military engineering conducted by the Navy in the 1930s and ’40s. TCE, classified in 2011 by the federal Environmental Protection Agency as a known carcinogen, meaning it causes cancer, was used by Grumman to degrease heavy machinery.

However, at the time, Grumman and the Navy were unaware that TCE was harmful to the public health and the environment, according to Edward Hannon, Northrop Grumman project director for its environmental health and safety program in New York.

In 1994, when the former Navy affiliate Grumman became Northrop Grumman, the company began investigating the contaminated water and worked with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation to develop plans to treat the plume. In the past 20 years, Northrop Grumman has designed and constructed an on-site groundwater containment and remediation system and has begun treatment on soil vapor and constructed groundwater treatment systems along the boundaries of Bethpage Community Park.

Nevertheless, the plume has continued to grow. “The plume got so large and out of control by being ignored,” Esposito said. “Now, the problem’s bigger, the plume is bigger, and the price tag is bigger.”

“The water is safe to drink because of the work done by the water suppliers, but we want to make that job easier for [them],” Curran said, “and we want to reassure our residents that going into the future, our water is safe to drink.”

According to Hannon, the plan is to draw contaminated groundwater from the ground, treat it at a treatment facility and return the clean water to the ground to replenish the aquifer. This is a system that Bethpage Water has been following for years to treat the contaminated water.

However, Boufis said that because of the size of the plume, eradicating it will be difficult. The treatment plan is “two decades too late,” Boufis said. “It makes the task now to do the cleanup and full containment remediation extremely difficult because the plume is deeper than anyone thought.”

Boufis estimated that the plume would be fully remediated in about 100 years, but he believes the bulk of the mass will be removed in about 15 to 25 years.

“The problem took a long time to spread, and it’s going to take a long time to fix,” Curran said, “but we have to start now or future generations are going to deal with this.”

Esposito said she worries about the long timeframe because it will be difficult to manage who will oversee and carry out the remediation process over the next century. However, she said she is hopeful that advancing technology will expedite the process.

Boufis said he believes the cleanup process is finally on the right track to clear out the toxic plume and restore clean groundwater because of recent action taken by government officials at all levels, Northrop Grumman and the Navy.

“The water industry has always been the silent service,” Boufis said, commenting on all the work that the Bethpage Water District has done and the money spent to treat contaminated water without government help. “It’s not really silent anymore. We’ve earned the respect of the federal government, the Navy and Northrop Grumman.”

While this is only the beginning, the cooperation of the federal and local governments, Northrop Grumman, the Navy and the water districts is a victory in Boufis’s eyes. “This battle has been epic as far as Bethpage has been concerned,” he said. “The little old town of Bethpage has taken on two giants [Northrop Grumman and the Navy], and I think it’s really coming to an end.”

Although there has been some conflict in the past between the Navy, Northrop Grumman and New York water suppliers, Boufis said he believes all parties are finally on the same page to protect the residents of affected communities.

“We remain absolutely committed,” Hannon said, “to pursuing scientifically sound, targeted and effective remedial approaches to protect the health and well-being of the community.”

Even with this plan in place and remediation under way, Esposito urges community members to “get up, show up and speak up” to continue the fight for a cleaner environment and optimal public health.

“The public’s voice really does matter, and it makes a difference,” she said. “This really is an issue that should galvanize all of us, bring us together, allow us to speak with one voice and cause us to be working in partnership to make sure we get clean water.”