By Urvi Gandhi

The 800-acre Shinnecock Reservation, between Shinnecock Hills and Southampton in Suffolk County, recently had solar panels installed on its preschool, signifying the first sustainable-energy project at the nation.

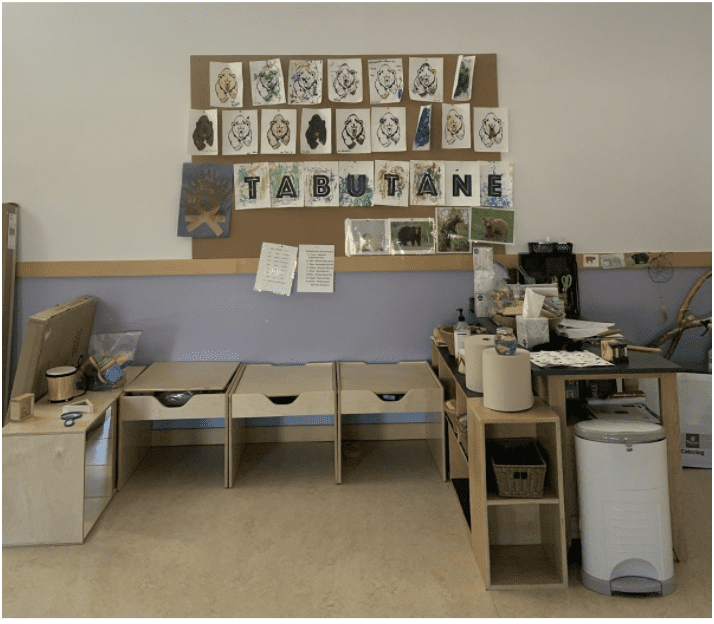

Retrofitting of the Wuneechanunk Shinnecock Preschool with the panels was completed Oct. 25 last year. The Shinnecock Nation, Long Island Progressive Coalition and the Ronkokoma-based SUNation Solar Systems, the installer, came together on the project.

Installation was done pro bono by the nonprofit arm of SUNation, SUNation Cares. “It’s really important that we give back to the community. We’re a very community-oriented company. That’s what SUNation Cares is all about,” said Gina Carrara, SUNation’s vice president of marketing and customer relations.

Since installation, the preschool’s electric bill has dropped from $2,000 a month to just over $300.

“It was good to see because we’re one of the most expensive buildings on the reservation, and it was a relief to have something that levels that,” said Natani Dennis, Wuneechanunk’s director.

Installation of the panels will serve as an educational tool so “kids that are very young can get exposed to this technology,” said Phillip Brown, the Shinnecock Nation’s housing director, adding that it’s “wonderful because it sets a whole new example about how we power our commercial buildings, our schools and our community.”

“And if they get exposed to it now and learn about it,” he said, “I think we have a great future with renewable energies for our nation.”

The tribe was connected to SUNation by Ryan Madden, LIPC’s sustainability coordinator, in December 2019. He explained that LIPC “has had for a few years an effort called PowerUpSolar Long Island, where we work with nonprofits, houses of worship and affordable housing developments to provide low-cost solar options for institutions that are pretty left behind in the renewable-energy economy.”

Installation plans were halted when the coronavirus hit in March 2020. The project was picked up again in September that year following more than a year of site visits, talks with the Shinnecock Council of Trustees and contract meetings.

Today, a free solar install was completed at Wuneechanunk Shinnecock Preschool thanks to our collaboration w/ @SUNationSolar & @ShinnecockGov. The project should serve as a model for how to move resources into the hands of Indigenous peoples as we transition off of fossil fuels. pic.twitter.com/xEXwYVuRmR

— Long Island Progressive Coalition (@LIProgress) October 25, 2021

Denise Merchant was the preschool’s interim acting director at the time of the installation and is now the nation’s educational and childcare consultant. Merchant championed the school as a candidate for the first solar installation at a tribal government building on the reservation in December 2019.

“We are one of the newest buildings on Shinnecock territory, so it would [have been] one of the easier starts,” Merchant said. The Shinnecock Nation’s “entire history as a people has been very clean and very natural . . . and what I’ve learned is that everything we’re doing at the preschool is a sort of example so we can further whatever goals we have towards clean energy and sustainability.”

The nearly 12.3 kilowatt project included 39 solar panels and 2,600 watt energy inverters.

According to SUNation, installation of the panels reduced the preschool’s carbon output by 90 to 95 percent.

The Long Island Power Authority aims to increase renewable energy generation on Long Island from 3 percent to 50 percent by 2030.

Native American tribes around the United States are increasingly using renewable energy to power their homes and economies. Tribal lands have major potential for renewable energy, most commonly solar and wind power. A 2013 U.S. Department of Energy study found that tribal lands could generate 14 billion MegaWattshertz (MWh) — or 5.1 percent of the U.S.’s total energy need.

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe of South Dakota, the Moapa Band of Paiutes and the Winnebago tribe of Nebraska have all made tremendous strides in implementing renewable-energy projects.

There are stumbling blocks, however, to further development. Installing solar panels on homes can cost $16,000 to $35,000, meaning people do not see a return on their initial investment for 20 years. According to SUNation, the approximate value of the donated system was $40,000.

“The cost has been a barrier for people to get [solar] on their homes,” Brown said. Outside the reservation, “you can put it up and wrap it in your housing mortgages, but on the reservation, we don’t have mortgages, so it’s not an option for us.”

Grants and nonprofit donations thus are critical in aiding indigenous groups and other communities in reaching net-zero emission goals.

“We have put our hat in the ring for a grant that would allow us to do an incredible amount of collaboration on energy efficiency and workforce development with the Shinnecock Nation,” Madden said. “We’re hoping this is the beginning of ongoing collaboration to support different facets of the transition for the nation. Institutions should have their ears and eyes out for ways that they can give back to the original stewards of this land.”

As reported by Shareable, battery storage could also be one of the upcoming undertakings that SUNation and the Shinnecock Nation could collaborate on.

According to Brown, future renewable-energy projects on the Shinnecock Reservation could include the community center, tribal office, health clinic, senior center or the upcoming Little Beach Harvest Cannabis Dispensary.