By Cody Hmelar

Indigenous peoples recently paddled from Maine to Long Island and up the Hudson River to Albany to raise awareness for the Montaukett Indian Nation and other Native American tribes. The Long Island Advocate’s Cody Hmelar was there to meet them as they stopped off at Jones Beach and in New York City. He produced this podcast to help chronicle their 1,500-mile journey.

Host lead: The fight for the Montaukett Indian Nation to be reinstated as a state-recognized tribe might have an end in sight with the passage of a new bill in the New York State Senate that passed unanimously on May 31. This comes after the Montaukett lost their recognition in the 1910 case Pharaoh v. Benson. The legislative action comes with increasing calls both locally in New York and nationwide for Indigenous sovereignty. Paddlers from tribes across country paddled more than 1,500 miles in the Northeast to practice their sovereignty and water rights. As we were recording this, the paddlers had just hit Lake Ontario in Oswego. I caught up to the canoers on their portion from Long Island to Manhattan.

[Song chant]

Quinna Hamby 0:00

CUT # 1: “[introduction in Skarò˙rə̨ˀ]… “Hi, my name is Quina. I’m from the Tuscarora Nation. I’m Turtle Clan. We’re part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. And I’m just so grateful to be out here today by the water.”

[fade in water splashing]

NARRATION:

That was Quinna Hamby. She just graduated from the University of Washington with her degree in women and gender studies.

[Quinna singing]

Most people at this point in their life might be searching for jobs. Quinna flew in from Seattle to New York to provide relief to paddlers on a canoe journey through the Hudson from Maine passing through New York.

CUT # 2: “It’s amazing to be back home at this time because I believe my journey started on the water and happened to be, you know, the canoe journey Nasquale with Hickory, who’s been such a foundational person in this canoe paddle here to Albany.”

NARRATION: Paddlers came from all over the Northeast to paddle from Penobscot, Maine, down the Atlantic seaboard to Long Island and up the Hudson River to Albany. This is an act of sovereignty for the paddlers but also raises awareness of the lack of recognition of Indigenous people across the United States.

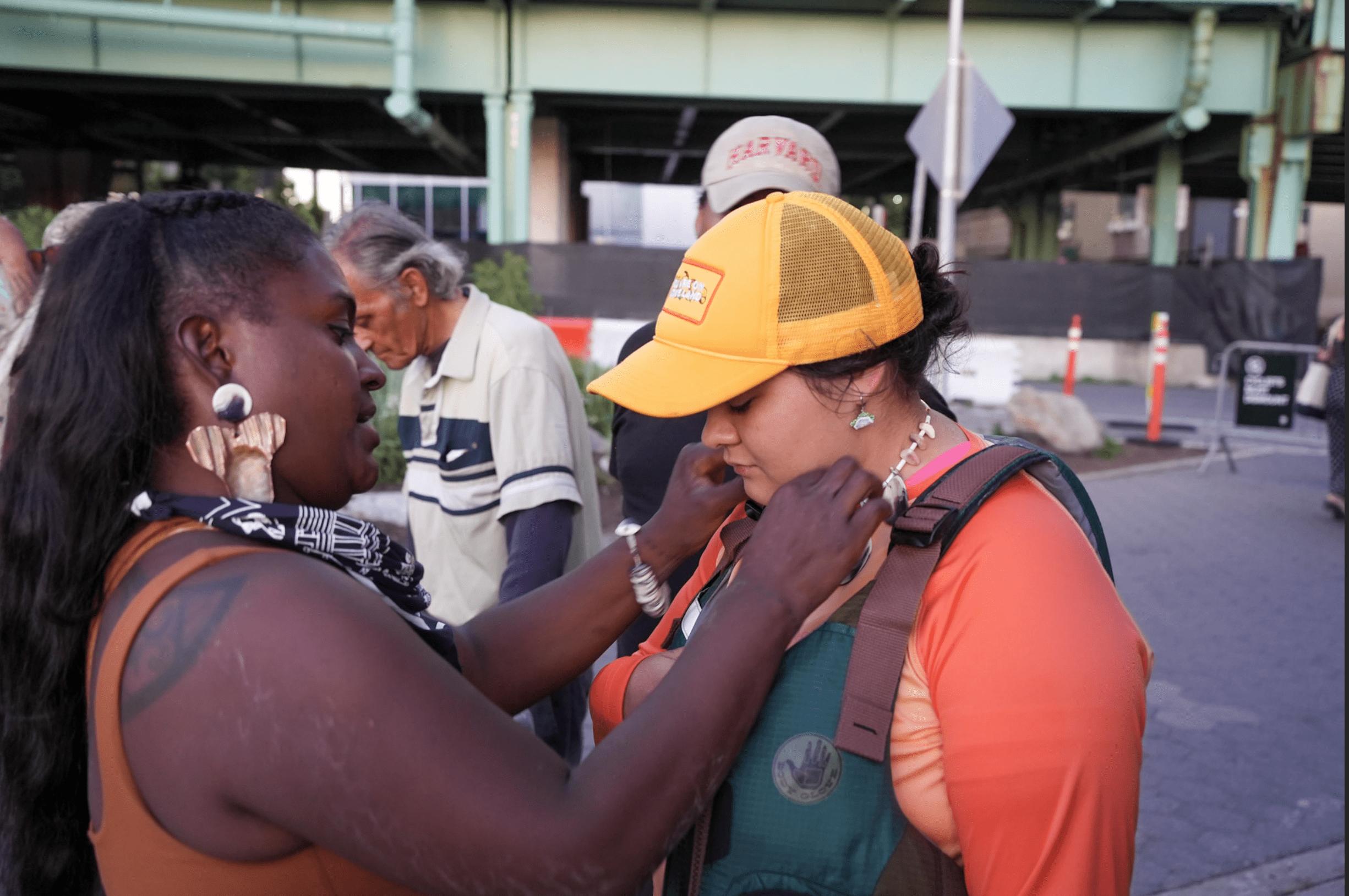

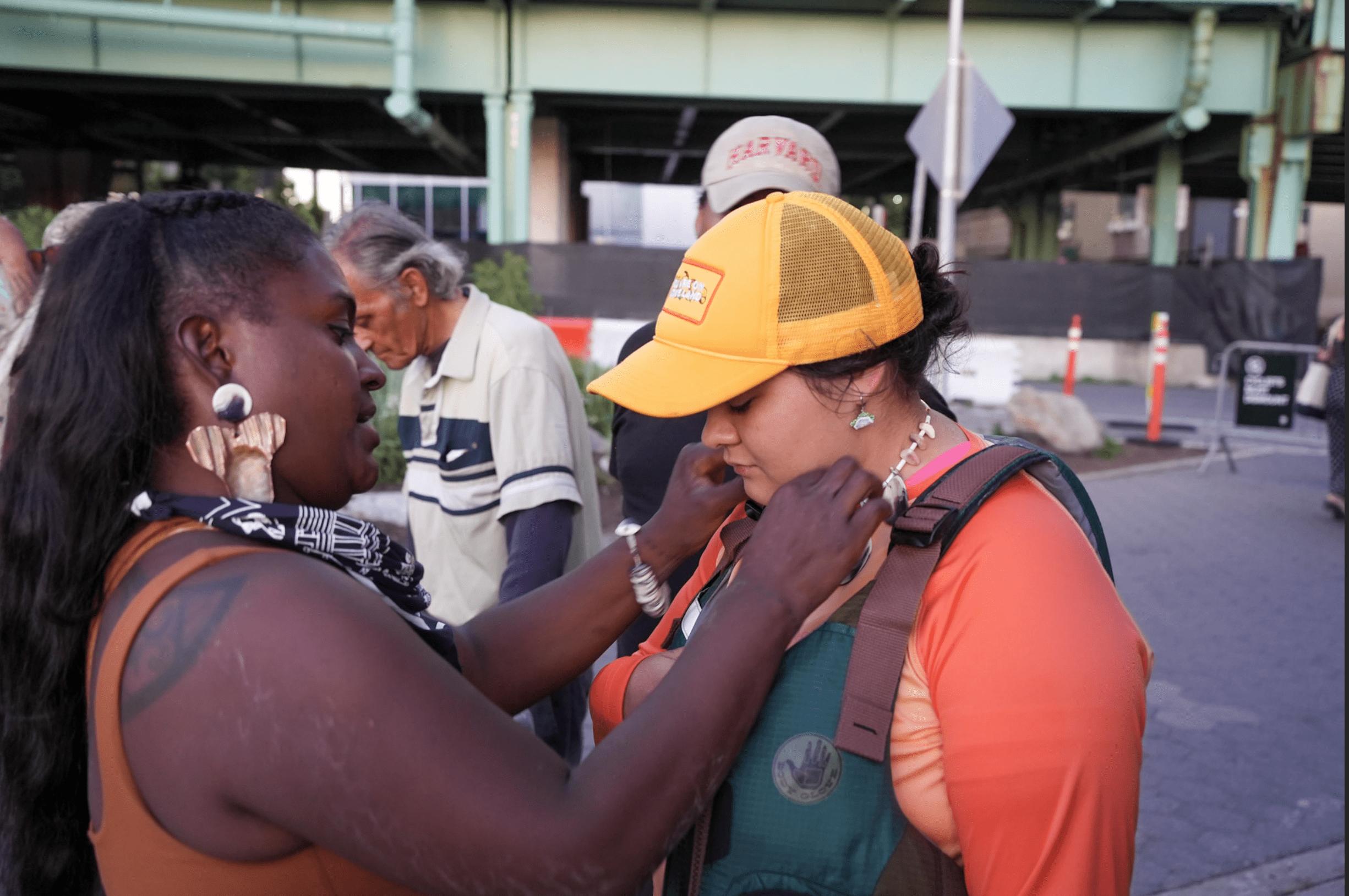

I joined these paddlers at Jones Beach. As we waited for over seven hours for the paddlers to arrive, the room filled with over 30 people from the Montauketts, Setalccott, to New York State park rangers and environmental protectionists.

Chenae Bullock, who led the journey from Boston to New York City, spoke about the visible demise of Indigenous people from their homelands.

CUT # 3: “We’re not necessarily welcomed in our own homes. We went through a lot to get here. A lot of things almost turned this trip around or almost stopped us and almost took our lives. And our elders started. came in at Nickerson Beach, one of the things he said to us was, “It’s a miracle that we are still here.”

CUT # 4: Sandi Brewster-Walker 1:07

“Over the years, people have almost tried to erase us. A lot of people don’t realize that they are tribal nations on Long Island.”

CUT # 5: John Strong 1:14

“The conception was that they died out. The myth of extinction, I call it.”

CUT # 6: Sandi Brewster-Walker 1:19

“…and that’s why they’re not taught in school. We’re the invisible people, and they think Indians all look like Indians west of the Mississippi.”

NARRATION:

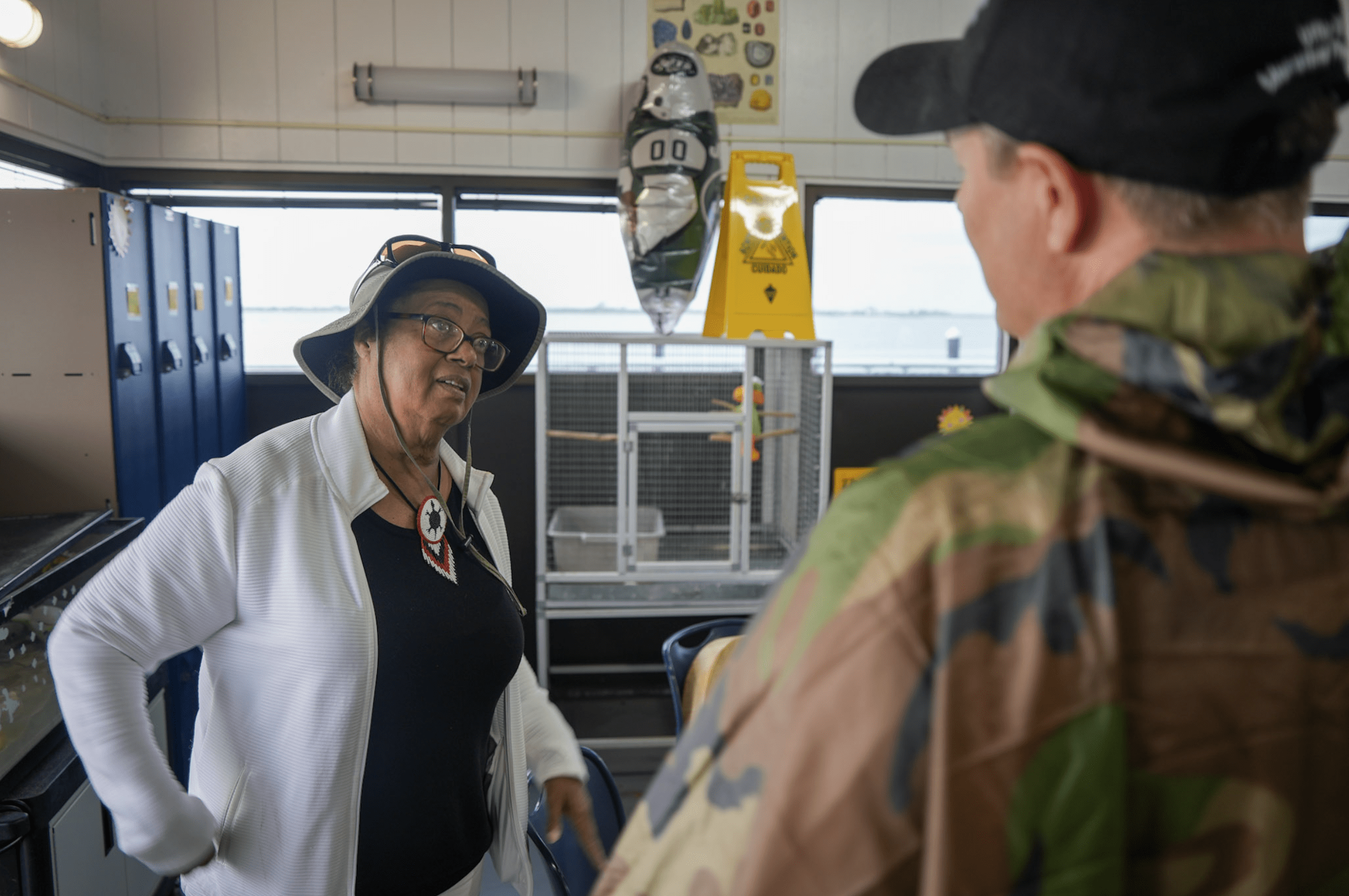

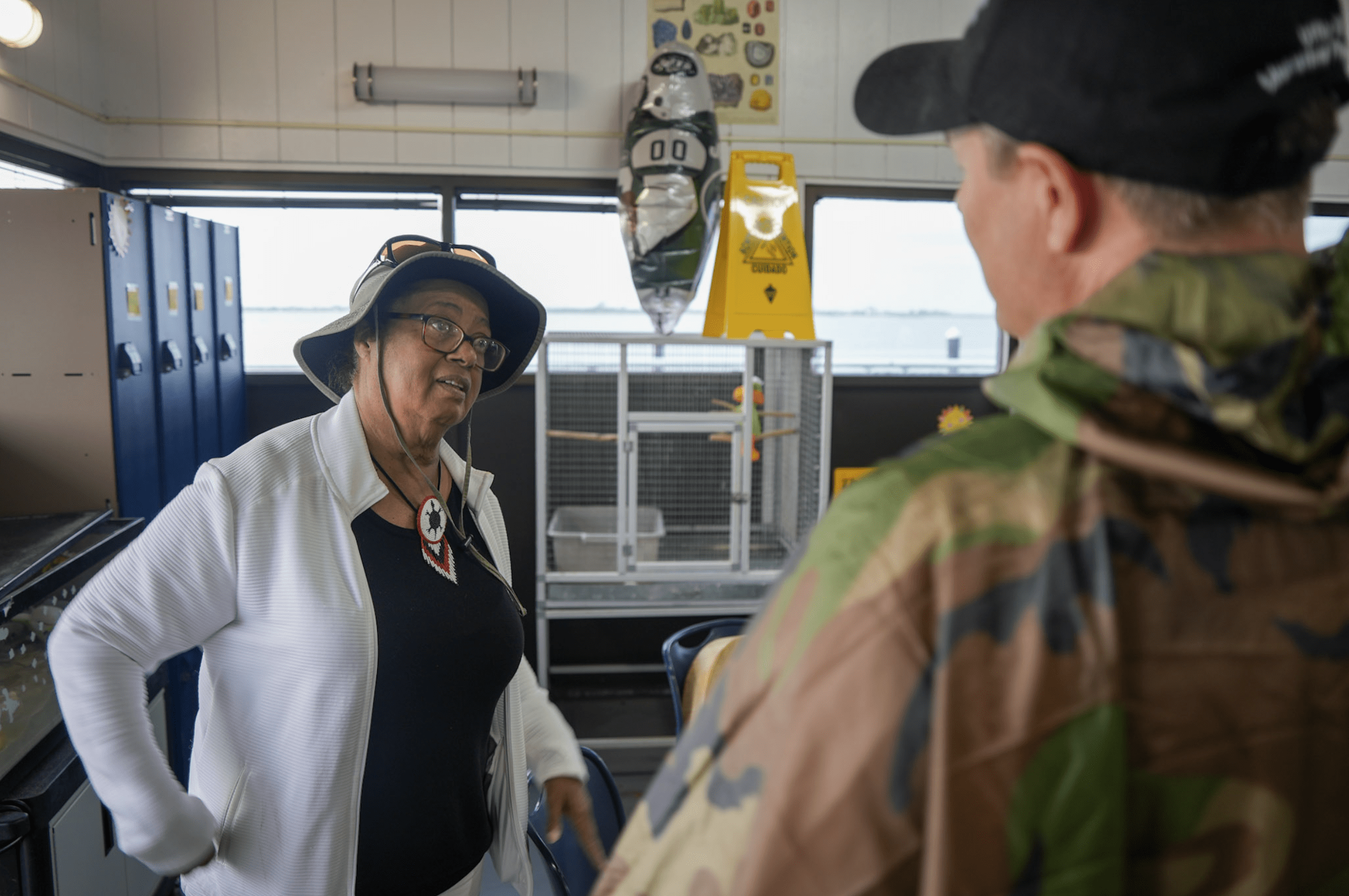

That was Sandi Brewster Walker, a government relations officer for the Montaukett nation who works in public policy and administration. We also heard the voice of John Strong, a historian who has focused much of his work on the Indigenous tribes of eastern Long Island. Both Brewster-Walker and Strong are leading proponents of Indigenous recognition on the island by both state and national governments.

Strong says that the process of getting federally recognized is challenging and selective.

CUT # 7: John Strong 1:28

“What nations are going to be invited to the dance, who are going to be invited to become a part of the federal organizations.”

Strong argues that the system of federal recognition of Indigenous tribes has been flawed from the start. It is a reflection of the colonial mentality that has shaped Indian affairs for generations. For example, Strong points to the role played by John Collier, the man credited with the restructuring of the reservation system. Strong says the Bureau of Indian Affairs has a skewed view of who and what native people were and are.

[STRONG]

“Collier had this interaction with Indians that by that point had been mainly from the Southwest, where he became very familiar with many Pueblo Indians. And so, in Collier’s mind, if you didn’t look like a Pueblo, you weren’t an Indian.”

[Sandi Brewster-Walker]

“…And as someone said to me, one day, I had on a business suit. And because I used to work for President Clinton, and as I mentioned, I was Indian, and they said, “But you don’t have a feather or anything,” stupid like that. And it’s said that TV has kind of distorted our image. And then students aren’t taught about the local Native American tribes, when they are taught about New York State history, they teach about the Mohawk, which has nothing to do with Long Island.”

Long Island is home to five tribal nations, but only two school districts on Long Island actively include them in history or cultural curricula. Part of the reason is due to a lack of awareness.

Quinna Hamby of the Tuscarora nation says the experiences of Indian nations on Long Island are not unlike what Indigenous communities around the world face when it comes to recognition and autonomy.

[Quinna Hamby]

“A lot of these discussions come up with the concept of what defines being Indigenous, or what is indigeneity.”

What defines someone as Indigenous? Why are some communities recognized and others marginalized, if not outright made invisible? It’s fair to say there are two main approaches to understanding why and how indigenous people have almost been erased on Long Island. Historian Strong says one is the intermarriage of indigenous people with African Americans.

[John Strong]

“That represents a further national concept of race and prejudice that there are basic racial groups in terms of skin color, white, Indian, and black. The hierarchy is, of course, white on top Indian or brown and middle black, you know, down south, they say, “Uf you’re, if you’re Brown, stick around, if you’re white, it’s alright, if you’re black, stay back.”

The other approach to understanding Indigenous erasure on Long Island goes back to when native people were enslaved all around the East Coast. Once again, Sandi Brewster-Walker:

[Sandi Brewster-Walker]

“So, in the 1600s, it became illegal to hold an Indian as a slave. So, you had people like Isaac Thompson with Hannah. Hannah was his slave of his and he issued two papers. One said, and only one said that she was Indian. And later on, she becomes Black because he couldn’t hold her as an Indian any longer.”

This retitling of native people as colored on the census occurred from the first census in 1790 to 1930.

[Sandi Brewster-Walker]

“You didn’t have to count them because we weren’t considered citizens.”

In every 10-year census, numerators, or the people tasked with administering the census, were instructed to put white if an Indian looked lighter-skinned and colored if they had darker skin.

[Brewster-Walker]

“That’s how the census records work, even though people would stay in and a lot of people in the areas knew who the Indian families were, but their race was being slowly changed by the sensus records.”

It is because of these census records that many fights for federal or state tribal recognition have been lost, even if they meet all the criteria set in the supreme court’s Montaya decision. This decision defined federal recognition as being based on the group having direct nation-to-nation relations with the federal government or with Congress.

In 1910, when the Montoya decision came out, the five nations of Long Island lost any possible standing they had. Until 2010, when the Shinnecock Nation became the first tribe on Long Island to receive federal recognition.

[John Strong]

“Both the Shinnecock and the Unkechaug had direct nation-to-nation relations with the colony of New York. And the Navy, both of them had any continuing historical existence since then, which is a basic criterion they had.”

In 1910, the story goes that in a courtroom of over 300 Montauketts, they were told they no longer exist. That the last of the Montauketts had died out. The reason? Commerce.

[Sandi Brewster-Walker]

“To erase us in 1910. They wanted to put the Long Island Rail Road out to Montauk Point.”

They wanted to make Montauk the official port of entry to New York and transport both passengers and cargo via train to Manhattan.

“But those damn Indians were in the way.”

A court case and New York State judge were all it took to strip away any rights or recognition that the Montauketts had.

“In 1910, there were 300 and some odd natives in the room when he declared us non-existent, and he didn’t have the right to, because the deputy director of the Department of Interior had made a statement that they didn’t have the authority to do that.”

Many historical documents will allude to 13 tribes on Long Island. This is incorrect and comes from the names of territories.

The five actual nations on Long Island are the Montaukett, Shinnecock, Unkechaug, Setalcock, and Mitinecock. The Montaukett are thought of as only existing in their namesake village, but they spread out from the North Fork all the way westward to Hempstead. This misinformation spread through history has only further led to the delegitimization of nations on Long Island.

[except from LIA]

“That was the thunderous crunch of the Shinnecock Nation striking again at its annual powwow open to the public for the first time since 2019.”

That’s from the Long Island Advocate reporting on the Powwow last year in 2022. This is one of the larger events on Long Island, and its public prominence is attributed as part of the reason the Shinnecock are still the only federally recognized tribe on Long Island. Chenae Bullock, a member of the Shinnecock Nation, criticizes the lack of acknowledgment of the various tribes, even cartographically.

[Chenae Bullock]

“Look at any map that shows tribes; you only see Shinnecock, which is the closest federally recognized tribe to New York City. It almost doesn’t even show that there are any other tribes, but how many have I just named?”

THE MISREPRESENTATION IN NAMING TRIBAL NATIONS ON LONG ISLAND goes back to the practice of identifying tribes by their territories. There are five nations but 13 territories. Over the years, the Montauketts of Massapequa became the Massapequa Indians. The notated history became fact. Major groups of people are isolated in the press and print.

[Sandi Brewster-Walker]

“So you have to kind of go back and DE-colonize the writing and look at who wrote what.”

While the Shinnecock are the only federally recognized tribe on Long Island, the Unkechaug are state recognized and hold de facto recognition in federal courts. THIS means they are protected from lawsuits. This still does not afford them the full rights and privileges of federal recognition. The remaining three tribes on Long Island, they’re still fighting for state recognition.

[Sandi Brewster-Walker]

“Most of the natives on Long Island, we’re all cousins, and we know each other, no matter what nation, people belong to. This is why, when I reworked the bill with the help of John and a couple of other people, we said, “Did we in statement not recognize because we already existed on Long Island?”

In May of 2023, the bill drafted by Sandi unanimously passed the New York State Legislature. The bill, if signed by Governor Hochul, would reinstate the Montauket as a state-recognized tribe.

While this is the fifth time a similar bill has been put to the state legislature, this is the first time it has passed unanimously.

This is considered a success for the reinstatement of the Montaukett people. However, many people are not even aware that Montauket exists.

[Sandi Brewster-Walker]

“Part of the problem is when Hofstra, Stony Brook or someone of the universities send their students out to do research, they send them to the reservation, and they just regurgitate what is already done, instead of doing new research.”

This leads to issues where despite public knowledge of the five tribes of Long Island in downstate New York, legislators from upstate New York are unable to find easily accessible and credible information when legislation gets voted on by Albany.

It has been riddled with inaccuracies from decades of selective preservation of oral history.

NAT AND OF SINGING/WATER…

That’s part of the reason for this canoe journey from Maine to Albany. To share the oral history and stories of their elders across each of the territories passed. It is historic in more ways than one.

[Chenae Bullock}

“So now that we’re able to do something that hadn’t been done since probably before the colonists arrived.”

[Quinna Hamby]

“We’ve been here for time immemorial. And those are our ancestral highways and how our people have been traveling since the creation.”

Bullock finds the New York City portion of this journey particularly special. Not only does it conclude her leg of the journey, but is a homecoming for her and her ancestors’ stories.

[Chenae Bullock]

“That’s where we met Hudson. That’s where that’s where the Algonquin speaking people met the Haudenosaunee people to trade Wampum, to trade shellfish, to trade furs, to trade all that, but there was a big interruption that took place. When the colonists came, they understood the value of our wampum. understood that and turned us against each other.”

[Quinna Hamby]

“It’s so important to know these waterways because they’re, you know, that’s where our people are from.”

New York City is known to have the largest number of urban-dwelling native people in the United States.

When I was chatting with Indigenous people from all over the world to witness these paddlers’ land, they observed what great destruction humanity can do to the land.

At Jones Beach, on the border of Nassau County and New York City, we see the final transition from nature to the concrete jungle. Bullock notes the parallels between the physical environment and the trends of colonized America.

[Chenae Bullock]

“We’re little outnumbered in this room, as far as the original people of this land. And that should be said that should be something that ought to be something that’s noticed as we get closer and closer to the city. Because when you came to Shinnecock, if you were there, it was nothing but Shinnecock people was nothing but Unkechaug people, nothing but Montaukett people. But as we get closer and closer to these areas, we’ve been pushed out. So to be able to paddle in some of the areas that we’ve been pushed out of is very historic in itself.”

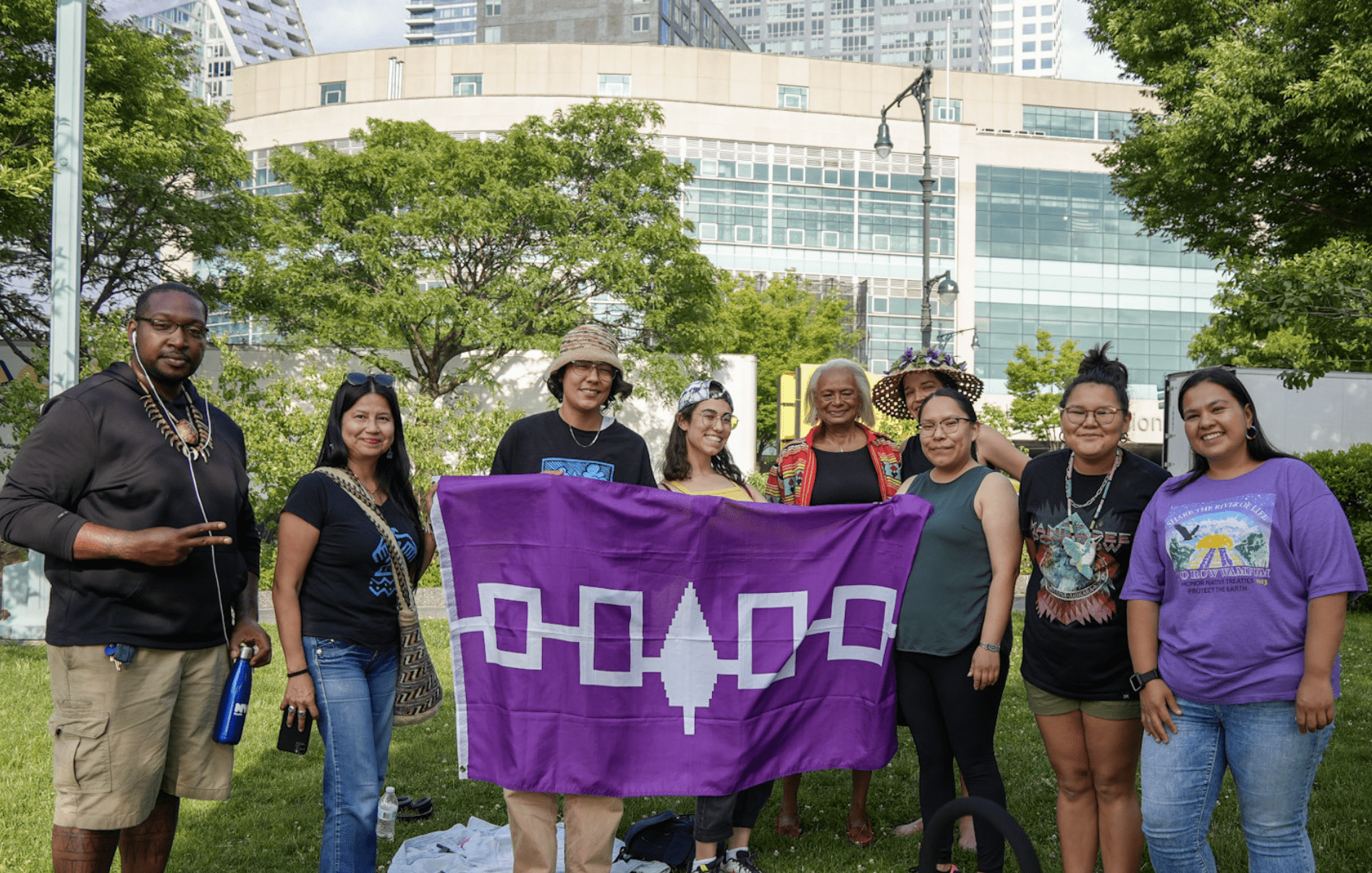

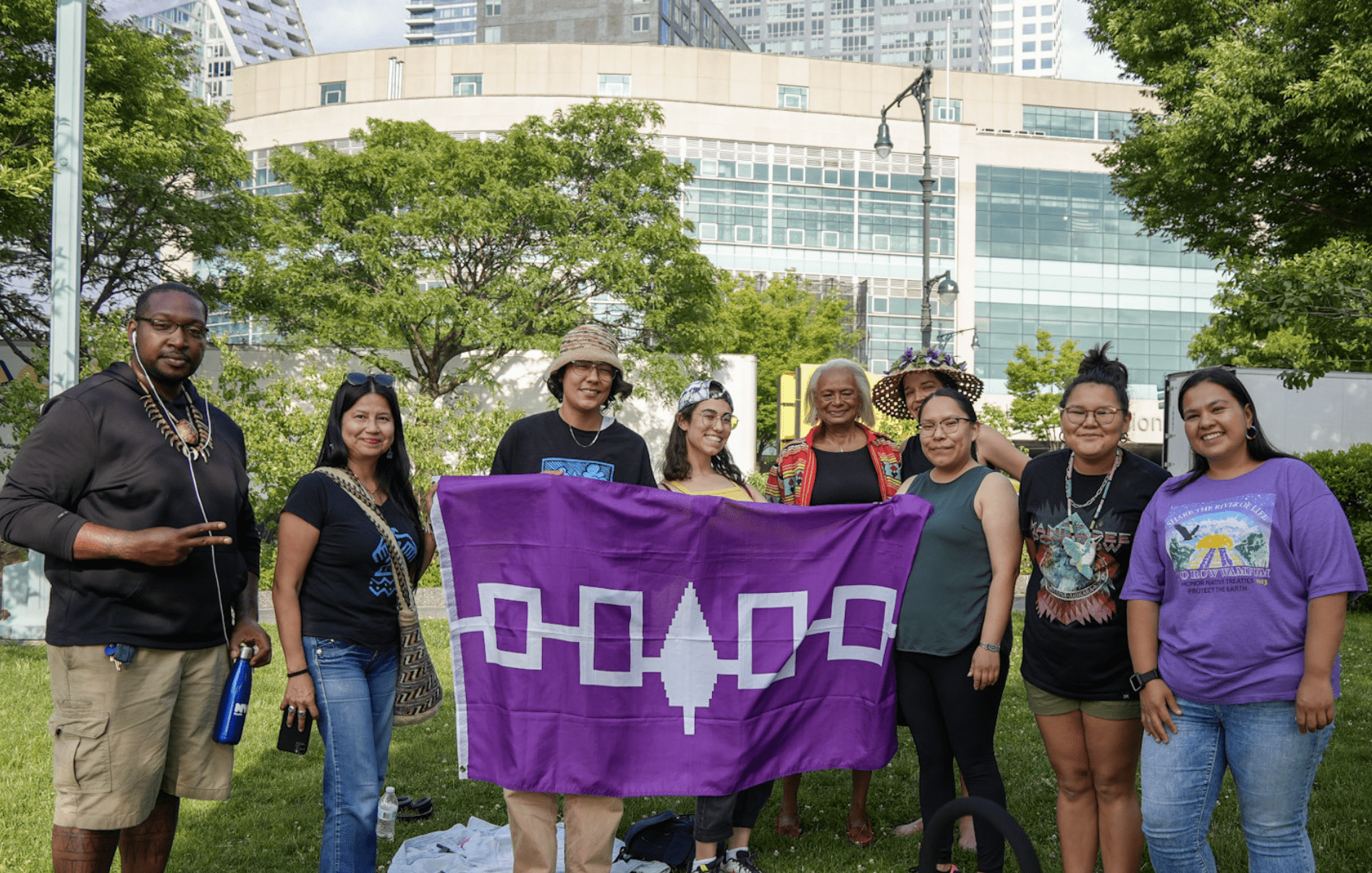

When I joined the paddlers again in Manhattan, in a group of over 10 people, to see that piece of nature restored amid urbanity. That’s power. Being able to experience that landing, with a heavy feeling of both joy and sorrow, people gathered from all over. ONCE AGAIN, QUINNA HAMBY…

[Quinna Hamby]

“Exercising that sovereignty is doing things like this because you’re reclaiming this, this practice of yours, of our ancestors. And the way that they used to travel was like using the portage and following these ways home. And it’s good to know that we can exercise our sovereignty by just simply living in our indigeneity and living as our authentic selves.”

[Chenae Bullock]

“We don’t need permission when we’re coming to our homeland. That’s something that we are showing every time we show up.”

The first step towards mitigating some of the harm incurred by colonial governments and recognizing indigenous sovereignty is awareness.

This journey is just one step in that direction. It is also the first major expedition on these waterways that are utilizing the internet to crowdfund and share their message.

[Sandi Brewster-Walker]

“Over the last 10 years, more people have verbalized their support for us.”

[John Strong]

“I think the myth of extinction is itself fading because you don’t hear the same kinds of rhetoric in the public media or such claims. Very seldom will people raise this question about the Shinnecock nation or the Unkechaug nation the way you did in the 60s when I first came here.”

The usage of the internet for both sharing of educational material but also social activism has paved the way for broader action and. Solidarity. John Strong says it’s noticeable.

[John Strong]

“The issue of extermination or fading away or extinction, so forth. That’s another reason why that isn’t heard that much anymore. It’s still around, but the internet made a big difference. You don’t see that challenge in public anymore.“

As I’m interviewing Quinna, where we’re on the water. A storm has just come for three hours. The paddlers were stranded on Fox Island by Gilgo Beach. The sun is finally shining again. Water calm despite this storm. Quinna is wearing a hat that says, “We are on native land.”

[Quinna Hamby]

“We’re still here, native nations are stronger than ever, and we’re gonna continue to create native futures and uphold our tribal sovereignties in that good way.”

From New York…I’m Cody HMELAR…