By Leah Chiappino

Editor’s note: This story first appeared in PULSE, which is published by the Lawrence Herbert School of Communication’s Magazine Production class for Hofstra University students and residents of surrounding communities.

Covid-19 first hit Long Island on March 5, 2020, and as of press time, had infected more than 310,000 Long Islanders, nearly six thousand of whom lost their lives. They were our friends, mothers, fathers, co-workers and neighbors. They were philanthropists, union members and church-goers. They were all of us. These are a few of their stories.

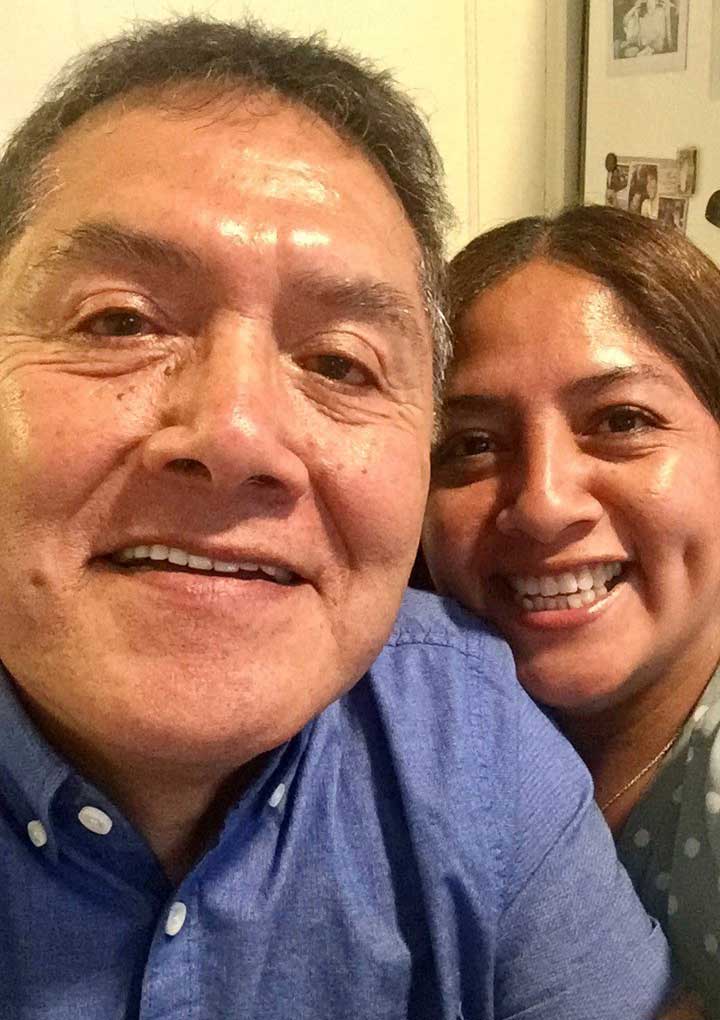

A LOVING FATHER AND PROUD IMMIGRANT

Pedro Braulio Vega Farromeque came to New York from Lima, Peru in 1986, in search of a better life for his family. Vega moved to Freeport when he arrived and found work as an electrician. As he worked to build a future for his children, his wife, Ana Vega, and two children had to stay in Peru because of immigration restrictions. They were able to join him two years later.

“He always mentioned that he felt proud he was able to give us a better life,” Vega’s daughter, Kathy Fee, said, growing emotional as she noted she was able to attend college and start a business because of her father’s sacrifices.

His son, Giancarlo Vega, described his father as the archetype of the patriarch in a martial arts movie; he was a generally quiet man, whose spoken words were filled with importance, and captivated everyone around him. “I remember when I was little, I was very intimidated by him because, even though he wasn’t tall in stature, his voice, presence and his demeanor always commanded respect,” he said.

Fee remembered the emphasis her father placed on receiving a sound education and striving for success. “He was very strict, and he wanted us to do well in school,” she said.

She remembered her father coming to pick her up from her grandmother’s house after school, where he made sure that not only his own children had their homework done, but also his nieces and nephews completed theirs too.“I would be on his lap,” Fee said, “and he [would] be asking them if they did their multiplication tables correctly, and check- ing their history, their language. That was my father.”

While family was most important to Vega, he was also an avid Mets fan, because the team had won the World Series in 1986, the year he came to New York. He loved the beach and was a devout Christian who attended church every Sunday. “It was work. family, and then church,” Fee said. Vega loved to travel, and fulfilled his life-long dream of visiting the White House.

In March of 2020, Giancarlo contracted the virus. Doctors informed him that as his father had similar symptoms to him, so it had likely spread throughout the household. Eventually, Giancarlo convinced his father to go to the emergency room. Once he dropped his father off, the family did not see Vega in person again.

“He always pushed for after-school activities and sports.”

A Great Neck Icon Who Spent Her Life Helping Others

As much as Sabina Miller loved Great Neck, Great Neck loved her back. “We would walk around town and everybody would stop my mother. She would say, “I could never have an affair,” her daughter, Eleanor Burnick said. Born to a family in the entertainment business, Miller spent her childhood on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. After graduating from the University of Miami, Miller married and had her two children, David and Eleanor. After she divorced, she moved her family to Great Neck in order to put her children in the best public schools. She worked in human resources at North Shore-LIJ Hospital, as well as in marketing in order to provide the best education for her children.

Burnick remembered Miller didn’t have a degree in marketing but was able to convince her colleagues and employers that she was qualified for the job. “If my mom put her mind to something, she did it amazingly well,” Burnick said. “She could convince you she had a degree in physics without actually having a degree. She was really, really good at saying, ‘I can do this,’ and then she would just do it. It wasn’t like it was a challenge for her.”

When Miller remarried four years later, the family moved to an apartment on Overlook Avenue, where Miller stayed for more than 50 years. An avid traveler, she stopped working in 1974 to join her husband, Irwin, on trips around the world, from Europe to the Dominican Republic. World travels weren’t enough for Miller’s restless spirit. She served on the Great Neck Beautification Committee and North Shore Hospital Ethics Committee, and volunteered for the State Ombudsman Program in nursing homes and the Children’s Learning After School Program in GreatNeck for decades. She was actively involved in the Kiwanis Club and the Lions Club for years. “My mom lived for volunteering,” Burnick said.

Through the Lions Club, Miller embarked on a trip to Easter Island in her later years, and ensured that more than 1,500 native children were fitted with glasses. Miller hosted and produced a number of programs on the North Shore Public television network, including “ Seniors for Seniors,” through which she encouraged other seniors to become involved in the community.“Sabina gave her time, energy, talent for engaging people and her nurturing personality to everyone she was involved with whether personally or professionally,” Grace Grella, the director of North Shore Public Television said. “Her light will illuminate the hearts of all who knew her forever.”

Miller suffered from dementia during the last year of her life and moved into a long-term care facility last November. Even with her mind fading, she still adored and boast-ed about her grandchildren, and spoke withBurnick on the phone five to six times a day. When she called Burnick on April 27, she said she couldn’t breathe. She was rushed to the hospital, where she died of Covid-19 36 hours later. Her family was unable to say goodbye to her in person because of the risk posed by the virus. “It kills me that she was by herself,” Burnick said. “She was my best friend. I miss her terribly.”

An Avid Church-goer and Bowler

Pauline Hribok may have been five days shy of her 94th birthday when she died of Covid-19, but her age hadn’t stopped her from making her weekly beauty parlor appointments, grocery shopping at ShopRite, counting the offerings at St. Luke’s Lutheran Church in Farmingdale every Monday morning and singing in the Prime Timers senior choir, which she was a member of for 60 years.

“She was still very much alive before the pandemic hit,” her daughter-in-law, Ellen Hirbok, said. “She was a woman that never left the house without her hair done or her makeup done. She was always put together perfectly.”

A native of Brooklyn, the elder Hribok graduated from secretarial school and married her husband, Dan, in 1949. The the couple moved to Seaford in 1959, and had two sons, one of whom they lost at only 3 months old. The couple’s younger son, Danny graduated from Hofstra University.

In her free time, Pauline was an avid bowler, having played and served as secretary of her local bowling team for more than 25 years. She loved reading mystery novels, filling out the daily crossword puzzle in Newsday and watching “Jeopardy.”

She was also an avid Mets fan, and always rooted for the great pitcher Tom Seaver, her favorite player.

Above all else, she adored her family. On Christmas Day, she would host a large gathering for her beloved siblings, nieces, and nephews. She always made her famous chocolate chip cookies — the secret, using Crisco over butter. She was married to Dan for more than 50 years, until his death eight years ago.

“They were very close,” Ellen said. “She was very well taken care of by him.” When Pauline moved to Emerge Rehab Nursing Home in Glen Cove to recover from a blood infection last April, her family didn’t know that would be the last time they would see her. “We were there maybe a half an hour, and then security came and said to us, ‘We’re locking the doors. It’s Covid,’” Ellen said.

The safeguards appeared to work for around three weeks until Pauline was one of the first Covid-19 cases in the facility. Hribok was put on oxygen and died three days later. “We were in shock and still are having a hard time understanding the whole thing,’ Ellen said. “She had so much more life left in her.”