By Yaw Bonsu

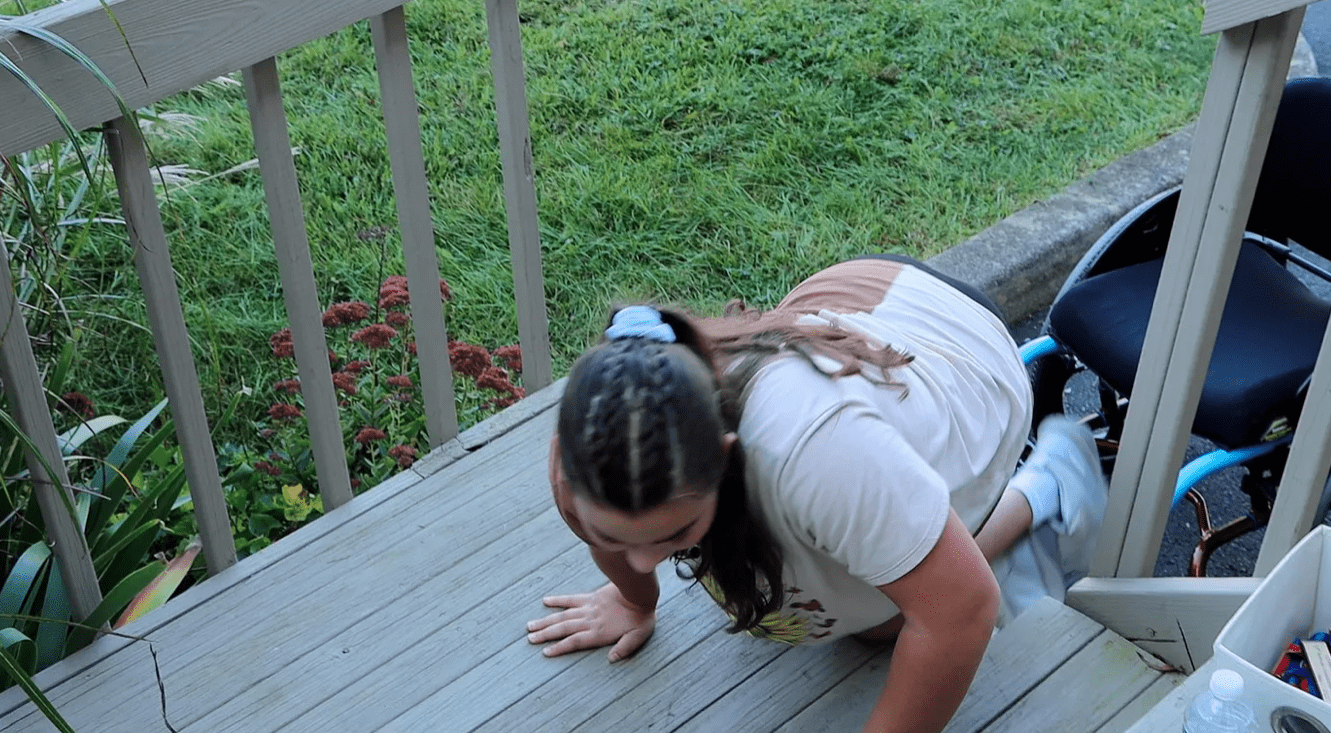

When 12-year-old Emma D’Antonio comes home from school, her routine is the same. No matter the weather, she lifts herself from her wheelchair, makes her way to the first step of her home and climbs up five wooden stairs on hands and knees to reach her front door.

Emma and her mother, Valerie, rent the top floor of a Bohemia home, a floor that is not accessible with a ramp or any other assistance for those in wheelchairs.

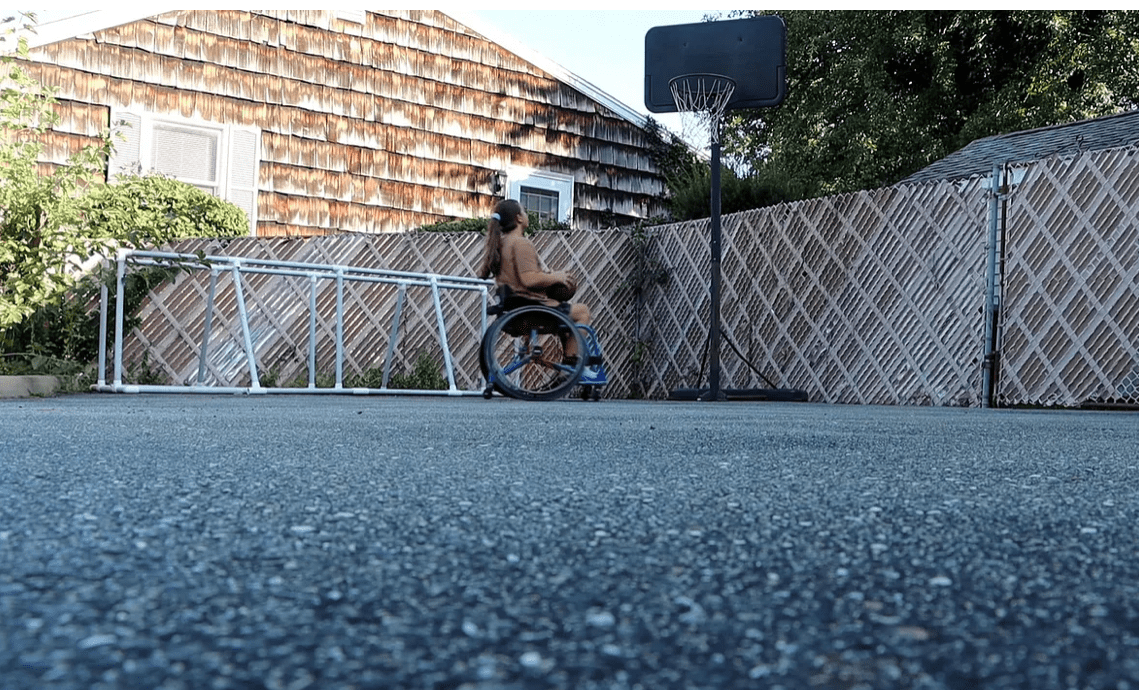

Then Emma climbs back outside, switches to her basketball wheelchair and starts practice in her driveway.

“She trains on her own. She’s always going up and down the block. She’s always practicing at her hoop,” Valerie said. “She’s always dribbling. She’s doing exercises to get stronger. Anything she can do, and she loves it.”

This has been Emma’s day-to-day life for a little over five years.

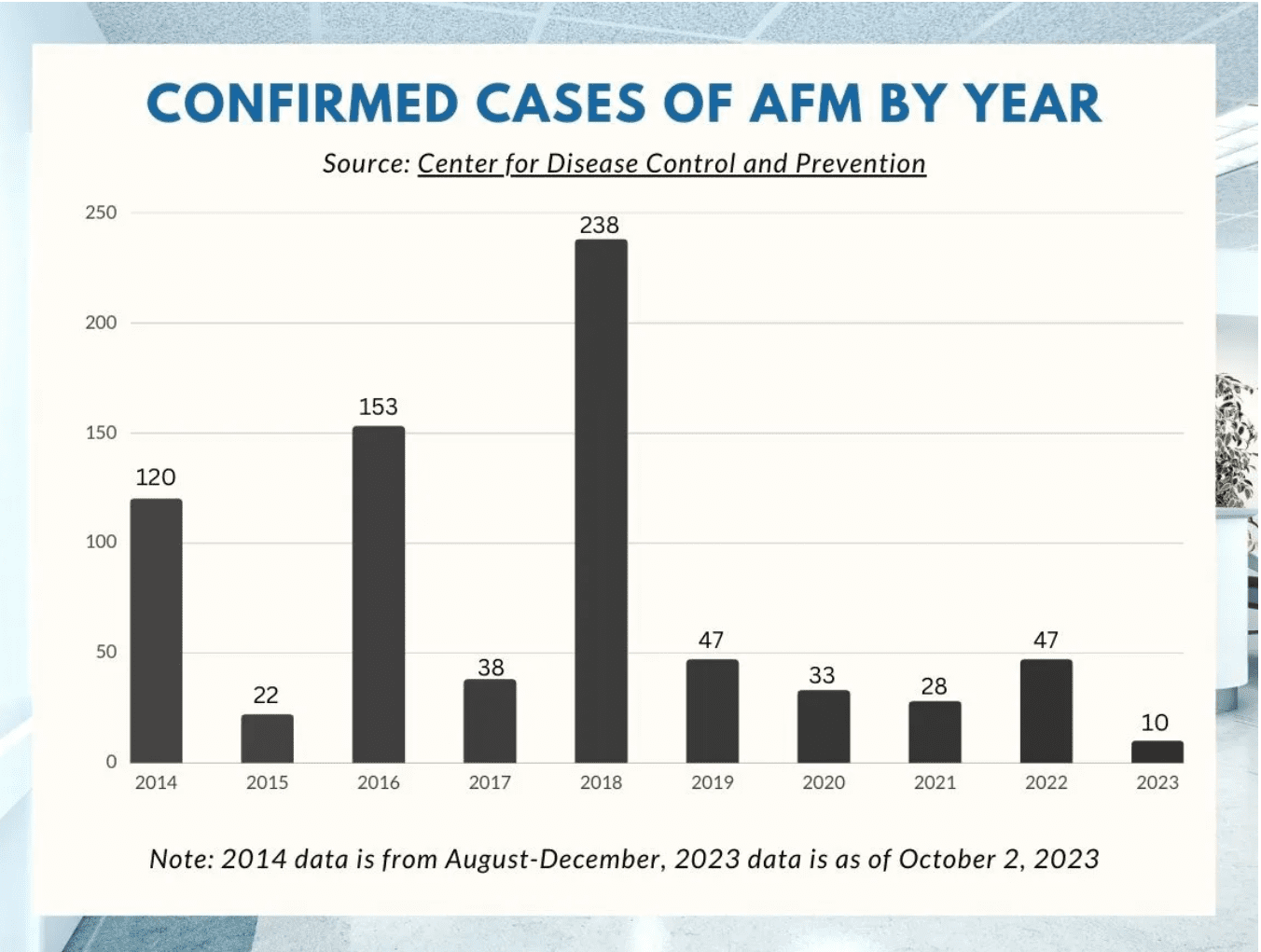

In 2018, the last known surge year for her condition, she was diagnosed with acute flaccid myelitis, a nerve-related condition that affects fewer than one in a million people in the United States each year. It’s attributed to a virus that causes the common cold and attacks the spinal cord and the nerves that lead into muscles.

“The way it was affecting her was even more rare because it was affecting the gray and the white matter in her brain. It was attacking her own spinal cord,” her mother noted.

On a 2018 trip to Pennsylvania, Emma began to feel pain in her lower leg.

“She had been canoeing and doing all the activities that we do at the lake,” Valerie said. “…As the night went on, her leg got worse and worse. She kept falling down.

“My mom realized that my leg was hanging funny,” Emma said. “My mom and my aunt thought that I just dislocated my hip.”

More than 200 people, mostly young kids, developed the polio-like condition known as acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) in 2018, federal health officials report.

— NBC News (@NBCNews) January 23, 2019

The CDC still does not have a prime suspect for the cause of the condition. https://t.co/XiGjdiy01i pic.twitter.com/RDL3HqjDux

After a trip to the emergency room, the D’Antonio family realized it was more than a dislocated hip. It was a matter of life and death.

“The ER doctor told me at that point, if I didn’t have her rushed to a children’s hospital, she probably would not survive the car ride home,” Valerie said.

“…the paralysis that had set in on her left leg was traveling up her body, and if it hit the part of her brain that affects your breathing…”

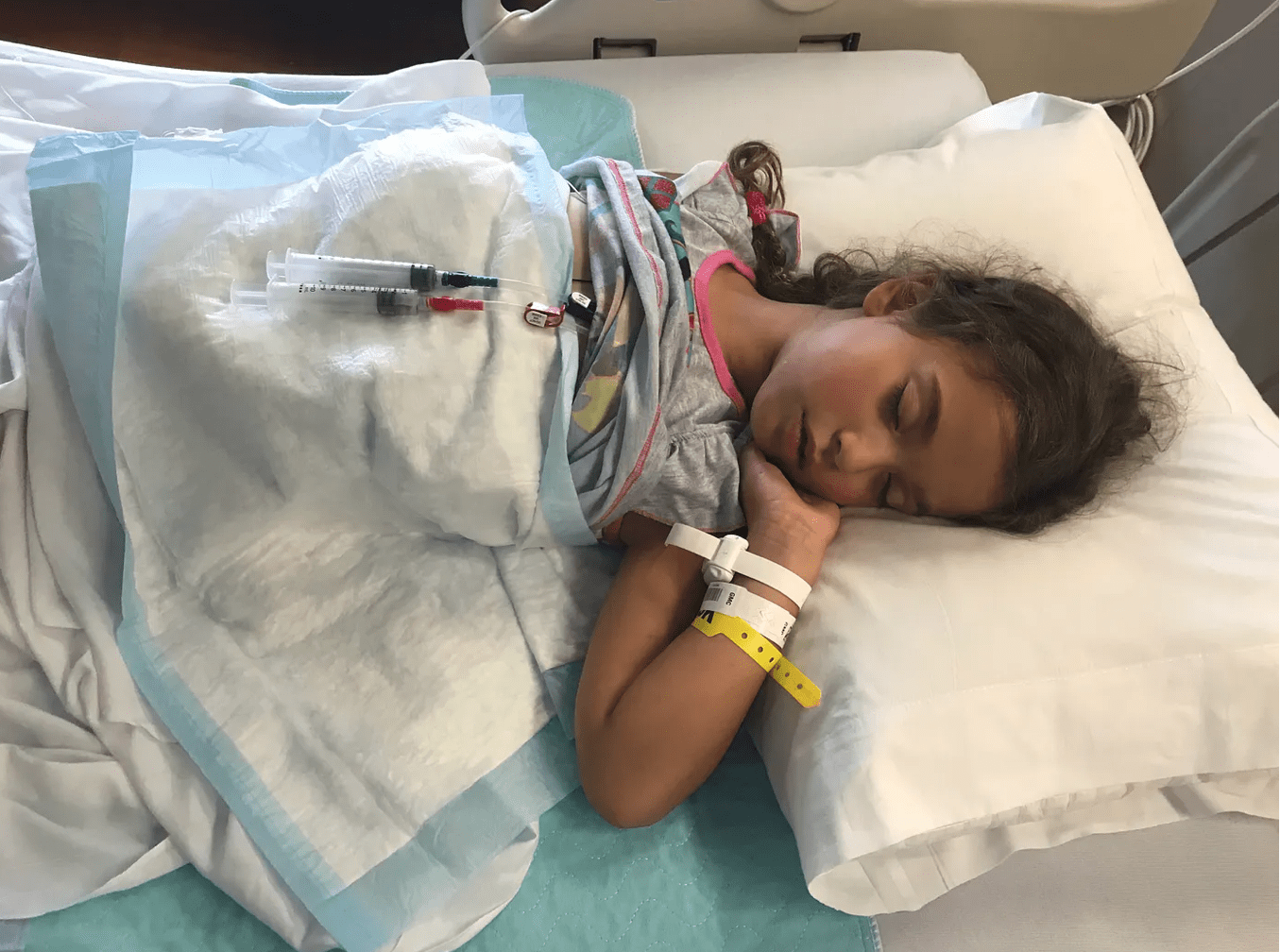

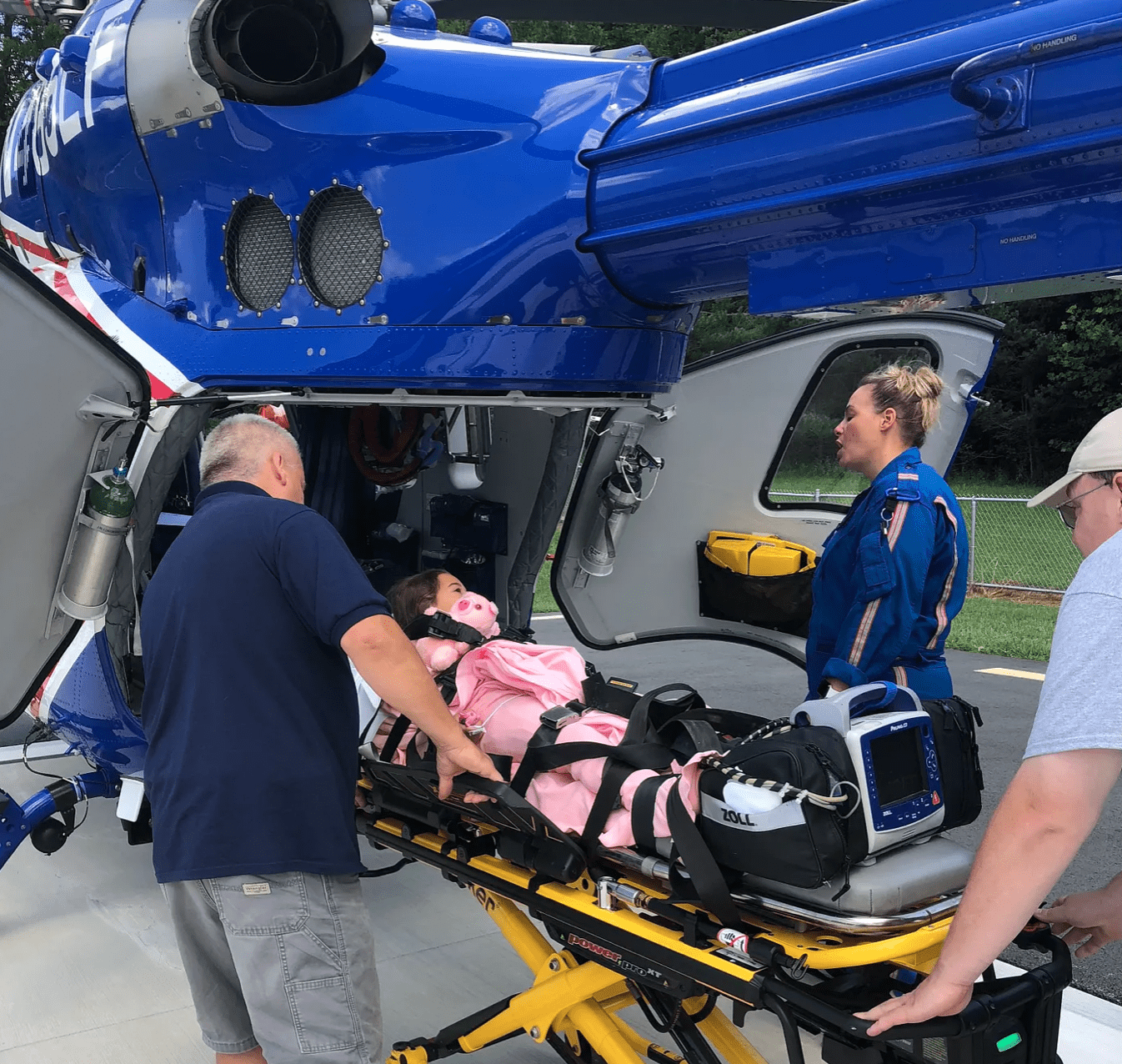

Emma couldn’t walk and could barely hold her head up. She had to be airlifted to another hospital for further testing.

Doctors tried everything from spinal taps to MRIs to blood transfusions to “everything they could think of.”

She was misdiagnosed four times.

“As a kid, you don’t really understand stuff…,” Emma said. “It took the doctor like two or three times to explain it to me, to understand what was actually happening.”

Emma would be in a wheelchair. She was diagnosed with one of the rarest cases of acute flaccid myelitis.

From August to the day before Thanksgiving 2018, Emma’s home was a hospital bed. As an inpatient, she slowly and rigorously worked her way through physical, occupational and aqua therapy.

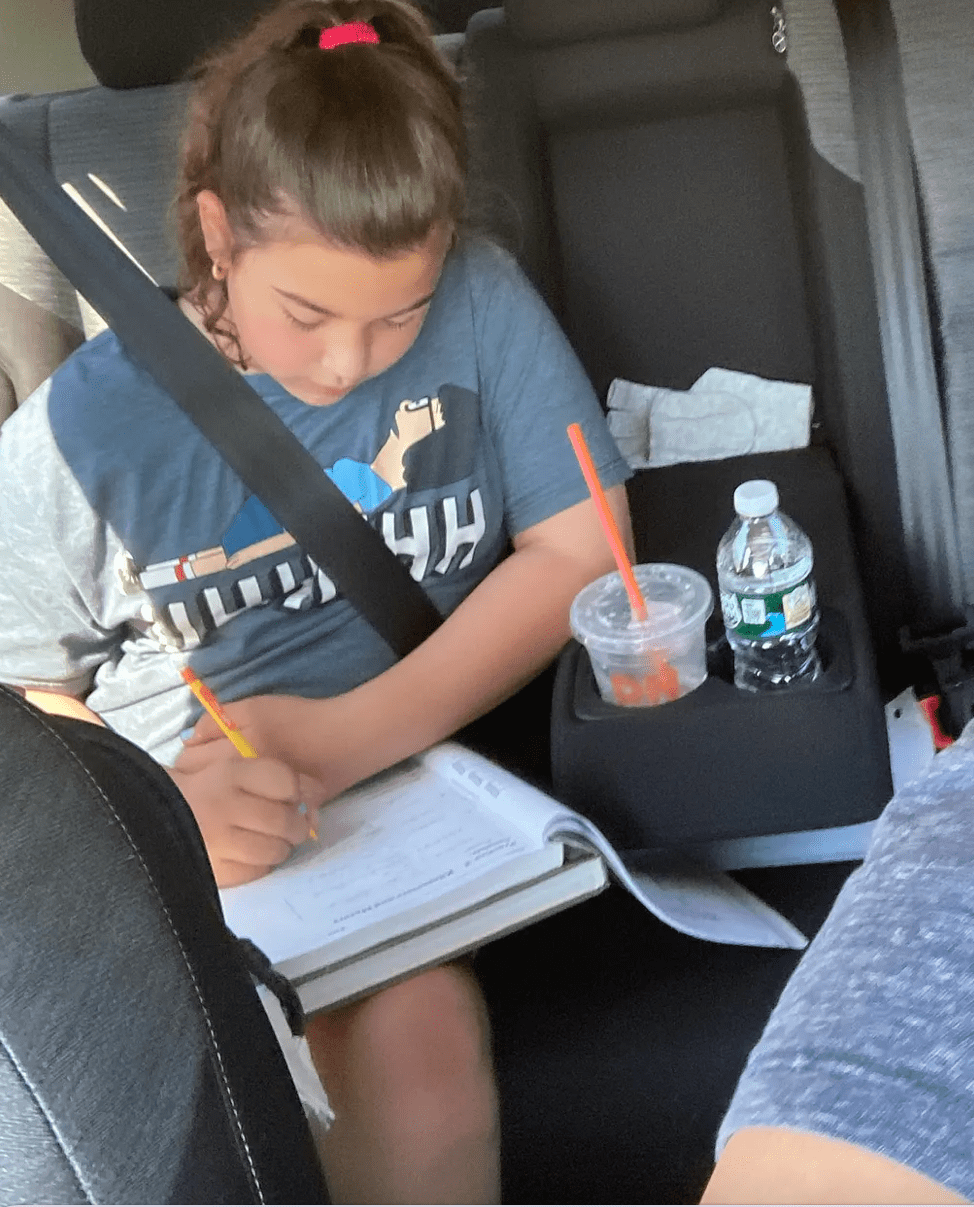

Virtual and distanced learning was introduced to Emma before the Covid-19 pandemic. The family, living on Long Island, had to travel for hours to Queens five days a week for Emma’s hour-and-half appointments once she became an outpatient.

Homework was completed in a car. Tutors and other aids offered help with more difficult concepts.

She missed out on in-person classes in first and second grades.

“It was upsetting because, you know, I had a lot of good friends in kindergarten, and I was really looking forward to seeing them again in first and second grade, and I just couldn’t because I wasn’t there for that,” Emma said. “Much of the day [was] figuring out when I can hang out with them over the weekend and figuring out when I can have play dates.”

At St. Mary’s Hospital for Children in Queens, Emma became only the second patient ever at the hospital to take part in locomotive therapy, an activity-based therapy that uses weights to challenge and strengthen muscles.

Still, Emma thought her life would consist of nothing more than eating, sleeping, and relaxing.

“I was upset. I definitely probably cried,” Emma said. “I was thinking that my life would just be, you know, I go to school, come home, lay on the couch, go on my phone and just do nothing.”

She was pleasantly mistaken.

A nurse at St. Mary’s invited Emma and her mom to a demonstrative wheelchair basketball game.

“Personally. I said no way. You’re not playing this,” Valerie said. “It’s too crazy. These people are nuts. They crashed into each other. They flipped their chairs.”

It took some classic little kid begging and a personal invitation from New York Rolling Fury head coach Christopher Bacon to bring Valerie on board and Emma onto the court.

“We packed up the car, we went to Queens, we went to the first practice, and ever since then she’s loved it,” Valerie said. “She wants to go to that more than no matter what else is happening. Wheelchair basketball is up here. Everything else takes a back seat.”

“It’s given me some friendships that I probably wouldn’t have had if I wasn’t in a wheelchair because I wouldn’t have met any of these kids,” Emma said. “It’s given me something to look forward to every week because we practice on Saturdays, so after Saturday, I’m already looking forward to the next practice because I need to play.”

Emma’s black-concrete driveway is her practice court. Her dead-end street is her treadmill. And to emulate crowd noise, she has the barking of the neighbor’s dog to keep her locked in.

As far as the crashing and potential flipping that comes with the sport, Emma found her way around that quickly. “I’ve learned how to control my chair better and how to fit into places if my chair’s too wide,” she said. “I know how to assemble a chair. I know how to put the wheels on. I know how to take them off. I know if I slip, I know how to get back into my chair or how to get up from it.”

By keeping up with her therapy and staying active with wheelchair basketball, Emma has regained motion everywhere except her left leg.

It is unknown what caused Emma’s condition, or if Emma will ever walk again. But since being diagnosed, Emma has racked up community support, a plethora of awards and even a new “everyday” wheelchair.

The ultimate goal? Playing on the United States women’s Paralympic basketball team

“You only get things that you can handle, and not only can she handle this, she’s exceeding it,” Valerie said. “She’s just breaking down every barrier.”

“I was able-bodied for my whole life up until then, and it was really just surprising and probably scary because I didn’t know what was going to happen,” Emma said of her illness. “I’ve learned to accept it, and I mean, if this didn’t happen to me, there would have been a lot of great friendships that I would have missed out on.”