By Roger De Chavez

More than half a century after Jim Crow laws were abolished with passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many Long Island communities remain segregated today because of systemic racism, experts say.

Dr. Alan J. Singer, author of “New York and Slavery: Time to Teach the Truth” and director of social studies education at Hofstra University, said, “African-American and now Latino families and Asian families have moved from the city out to the suburbs, but the tendency has been, as communities have become more diverse, they then re-segregate, as white families with children don’t move into those communities.”

Singer based his conclusions on research that he conducted for a piece for George Washington University’s History News Network, in which he discussed how certain Long Island villages still face racial segregation in schools.

Malverne: The Incomplete Struggle for School Integration on Long Island – Alan Singer on History News Networkhttps://t.co/H5iPysLn8i

— Alan J Singer (@AlanJSinger1) February 21, 2022

Singer said he believes current Long Island segregation stems from real estate redlining practices that date back to the post-World War II era. Back then, bank lenders used red marks to outline communities of color that they intended to keep racially segregated.

Those patterns of segregation “were set in the ’50s and ’60s,” Singer emphasized, and they continue today.

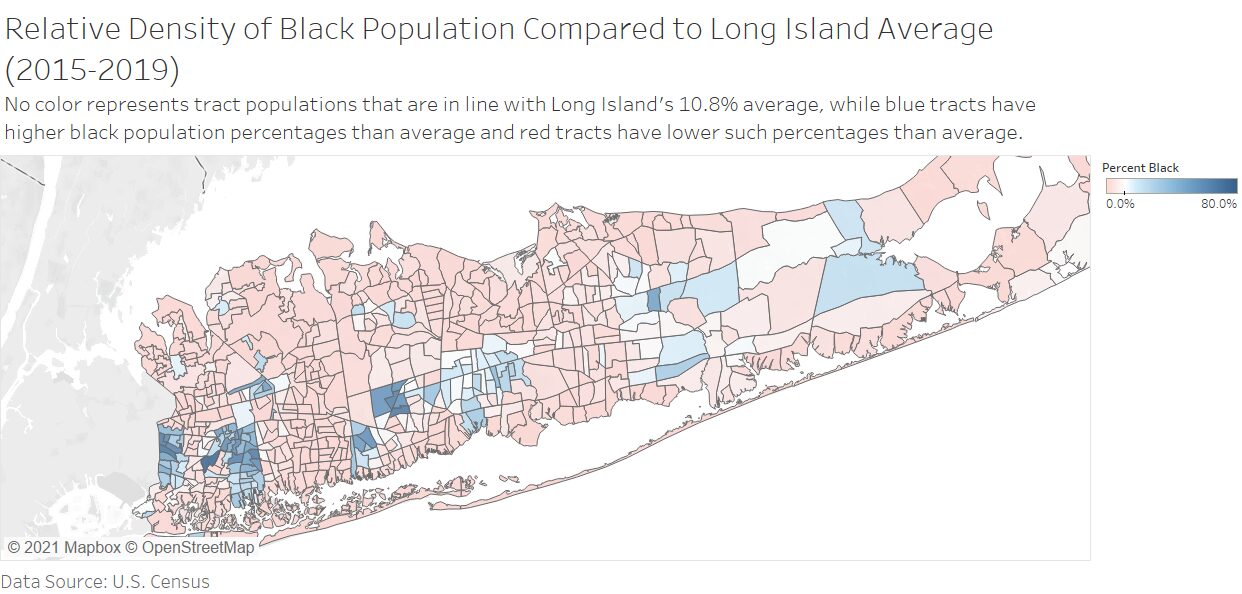

Half of Long Island’s Black population lives in just 11 of the region’s 291 communities, and 90 percent in only 62 of them, according to Newsday’s award-winning 2019 series “Long Island Divided,” a three-year investigation into the redlining practices of several of Long Island real estate agents.

ERASE Racism is a Syosset-based research and advocacy organization that focuses on identifying and ending racial segregation on Long Island. Olivia Ildefonso, the group’s former housing and communications coordinator, said she believes redlining on Long Island results from historic federal policies that have placed a disproportionately high value on white-owned housing compared with that owned by people of color, driving up prices in white-owned neighborhoods and excluding anyone who cannot afford them. Segregation thus becomes institutionalized — systemic.

“Because the federal government determined that white homogenous neighborhoods are the ones that are going to be valued the most, they’re the ones that are going to have the highest property values,” Ildefonso said.

One Long Island real estate agent, who did not wish to be identified, said, ” . . . Some of the communities, some people wanna move out of them and move into a different neighborhood and they do. Is it frowned upon? Yes . . . A lot of brokers wanna keep things a certain way, [but it] doesn’t always turn out the way that you want, you know?”

The agent, who claimed never to have practiced redlining, said many brokers and agents today still “tell certain cultures, ‘You can’t live here because we don’t want you to be here because you can drive the price of the house down.’”

The coronavirus pandemic, however, may have shifted that thinking to a degree. Many real estate agencies’ main goal these days is to “just make the deals because [the] economy’s suffering and people need money,” the agent said.

Singer said he believes the solution to ending housing segregation lies in strong political and government reform. “We need politicians and local officials to stand up to say, ‘This is wrong,'” he noted.