By Annemarie LePard

Pharmaceutical companies have been blamed and punished for the opioid epidemic for years, but they are not entirely at fault, according to experts. Physicians and pharmacies also played their parts.

“The doctor is illegally writing scripts,” New York Assemblyman Richard Gottfried, the Health Committee chair, said. “The drug manufacturer may be hiding information about the negative effects of a drug or may be improperly making it. And then the pharmacy may be either knowingly, or grossly negligently, participating in a whole set of transactions.”

Physicians, drug manufacturers and pharmacies, however, are only providing services that society wants, experts say. The crisis stems from a supply and demand for opioids across the country.

“If the demand is high, then somebody is going to supply it,” said Paul Fisher, professor and vice chair of the Department of Pharmacology Sciences at Stony Brook University. “And there is enough poverty and enough misery in the world to guarantee that supply will be forthcoming.”

In the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies “reassured” the medical community that patients would not become addicted to prescription opioid pain relievers, and healthcare providers began to prescribe them at greater rates, according to the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

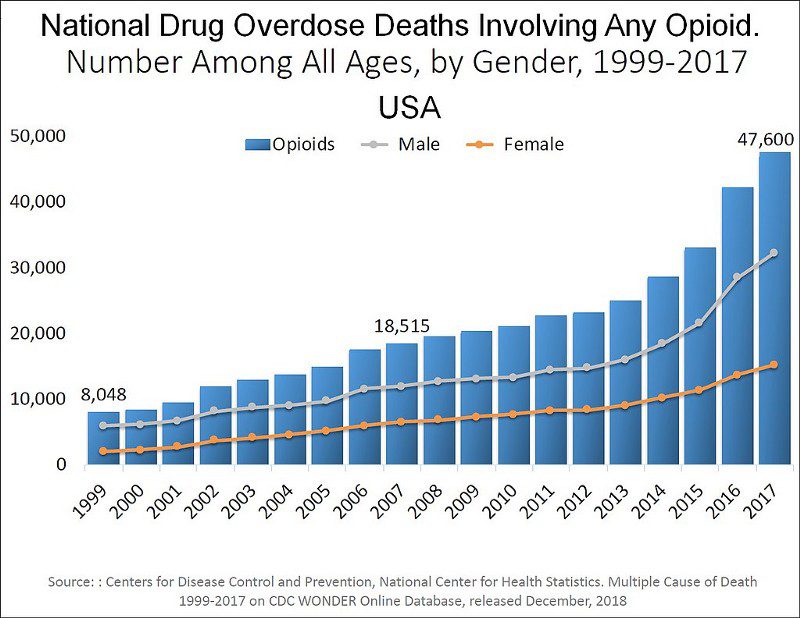

With opioid overdoses now killing thousands of Americans, state governments are introducing new regulations in an attempt to end the epidemic.

The new regulations, however, are causing many physicians to “shy away from using opioids because they are so highly regulated,” according to Fisher. “I was taught as a student never to be afraid of using opioids to treat pain.”

Gottfried agrees there is a fear doctors have when it comes to prescribing controlled substances, but he believes there is another factor that contributes to under-prescribing.

“Some of that is doctors who just don’t appreciate the severity of pain, and there are also doctors who under-prescribe pain medication because they are concerned that a patient might get addicted, or concerned they might get in trouble,” Gottfried said.

Savall Drugs, an independent pharmacy in Merrick, does not carry opioids regularly because doctors have a “fear of prescribing them.”

“I spoke to the cardiologist across the street, and he doesn’t prescribe controlled substances,” Savall owner Bob Klieger said. “I asked him why, and he said he just gives ibuprofen because he doesn’t want the [federal Drug Enforcement Administration] looking through his records.”

According to Fisher, there is a substantial risk that comes with people overreacting. “Patients who need pain management of the highest order will have trouble getting it in an attempt to limit illicit opioids,” Fisher said. “These are really useful, really important drugs, and it’s a shame that they are so abused, or [have] the potential for abuse.

“Patients with end-stage cancer, with rheumatoid arthritis, to just name a few illnesses,” he continued, “should never wish for death because it hurts so bad.”

Distribution of Controlled Substances

In 2013, New York state approved two laws that changed the distribution of controlled substances in order to reduce “doctor shopping” and “over-prescribing.”

The Prescription Monitoring Program, formally referred to as the Controlled Substance Information Program, gives practitioners “access to review their patients’ recent controlled substance prescription history at any time, therefore giving [practitioners] more information to exercise their professional judgment in treating their patients,” according to the New York Chapter American College of Physicians.

Practitioners are required to consult the PMP Registry in “most cases” before prescribing any controlled substance listed in Schedule II, III or IV; however, pharmacists are “not required to consult the registry, as stated by the New York State Department of Health.”

“The pharmacist basically relies on the fact that the prescriber, who makes the judgment whether to write a prescription, is required to consult it,” Gottfried said. “The decision whether the information in the database would give you pause about prescribing a controlled substance to a particular patient is really the physician’s judgment, not the pharmacist’s.”

A pharmacist’s main job is to ensure all prescriptions are dispensed properly, “and that’s why checking the monitoring program is the prescriber’s job, not the pharmacist’s job,” Gottfried said.

In August 2013, the I-STOP Act, also known as the Internet System for Tracking Over-Prescribing Act, took full effect across New York state. The law was proposed to stop “doctor shopping,” according to Amanda Cioffi, a school social worker.

“A lot of people in the early 2000s were getting prescriptions from three or four doctors in a row. Then they were able to go to their pharmacy and get a large amount of controlled substances,” Cioffi said. “And the pharmacy had no way of tracking it, so it’s kind of like they were just dispensing controlled substances to people.”

The I-STOP Act put an end to over-prescribing, and enabled doctors and pharmacists to provide prescription medications, and other controlled substances, to patients who truly need them.

“Unfortunately, people fell into heroin,” Cioffi said. “Because [people] could no longer get their prescriptions [filled], they turned to something a lot cheaper.”

The I-STOP Act also eliminates the problem of “stolen and forged prescriptions being used to obtain controlled substances from pharmacies; facilitates prosecutions of crooked doctors; and achieves significant savings for public and private health insurance program,” according to State Attorney General Letitia James.

Future Efforts to End the Crisis

Nassau County has filed a lawsuit against more than a dozen drug companies and distributors, health care providers and major companies, including Walmart, CVS and Walgreens, according to News 12 Long Island.

West Islip attorney David Grossman, who represents Island Park, said the suit is for “economic damages related to the opioid crisis,” including the cost to administer emergency response services to overdoses and use of Narcan.

The trial began Jan. 20.

“There are a lot of ill-informed people, ill-informed with respect to the basic science of opioids,” Fisher said. “I’m worried that we’re being pressured into making some poor, or ill-informed, decisions really quickly without taking the time to understand the problem and all of its ramifications.”

As a pharmacologist, Fisher’s responsibility is to inform and to provide as much accurate information “in what are very large socioeconomic, political decisions” in dealing with controlled substances.

“In educating physicians, it is [my job] to make them aware of how dangerous opioids are, how valuable they are, how they will lose a valuable tool if they’re not aware of the dangers and handle them accordingly,” Fisher said.

“What is needed is more and better education, and prevention and treatment programs,” Gottfried said.

Questions to Ask Your Pharmacist From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- What is this medicine supposed to do?

- How and when should I take it?

- What are possible side effects? What should I do if I get them?

- Should I avoid certain activities, like driving or running?

- Should I avoid certain foods while taking the medicine, such as milk products or grapefruit?

- If I’m having problems with this medicine, when should I call my doctor?

- Can you give me a list of my prescribed medicines?